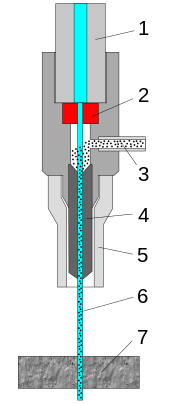

- 고압의 물 유입구

- 보석 (산업용 루비나 다이아몬드)

- 연마제 (석류석)

- 믹싱 튜브

- 보호막

- 워터젯 절단

- 절삭할 물체

워터젯 절단기, 워터 제트 커터(water jet cutter), 워터젯(waterjet)으로 알려져 있는 도구는 물의 고압 분사 또는 물과 연마 물질의 혼합물을 사용하여 다양한 재료를 절단할 수 있는 산업용 도구이다. 연마 제트라는 용어는 금속, 돌 또는 유리와 같은 단단한 재료를 절단하기 위해 물과 연마제를 혼합하여 사용하는 것을 의미하며, 순수 워터젯(waterjet) 및 물 전용 절단(water-only cutting)이라는 용어는 나무나 고무와 같은 부드러운 재료에 사용되는 연마제를 추가하지 않은 워터젯 절삭을 의미한다.[1]

워터젯 절삭은 기계 부품을 제작하는 동안 자주 사용된다. 절단되는 재료가 다른 방법에 의해 발생하는 고온에 민감할 때 선호되는 방법이다. 재료의 예로는 플라스틱과 알루미늄이 있다. 광업과 항공우주 등 다양한 산업에서 절삭, 성형, 리밍에 사용된다.[2]

역사

편집워터젯 (Waterjet)

편집고압수를 침식에 사용하는 공법은 1800년대 중반까지 거슬러 올라가 수력 채굴과 함께였지만, 1930년대에 이르러서야 좁은 제트 방식으로 물을 고압으로 분사하는 방식의 산업용 절삭장치로 등장하기 시작했다. 1933년 위스콘신주에 있는 회사 페이퍼 패텐츠(Paper Patents)는 연속된 종이의 묶음에서 수평으로 움직이는 종이를 자르기 위해 대각선으로 움직이는 워터젯 노즐을 사용하는 종이 계량기, 절단기, 그리고 휘는 기계를 개발했다.[3] 이러한 초기 응용은 저압력에서 이루어졌으며 종이와 같은 부드러운 물질로 제한되었다.

워터젯 기술은 전 세계의 연구원들이 효율적인 절단 시스템을 위한 새로운 방법을 찾으면서 전후 시대에 발전했다. 1956년, 룩셈부르크의 듀록스 인터내셔널(Durox International)의 칼 존슨은 얇은 강물 고압 워터젯을 사용하여 플라스틱 모양을 자르는 방법을 개발했지만 종이와 같은 재료는 부드러운 재료였다.[4] 1958년 북미 항공의 빌리 슈와차(Billie Schwacha)는 초고압 액체를 사용하여 단단한 물질을 절단하는 시스템을 개발했다.[5] 이 시스템은 10만 psi (690 MPa) 펌프를 사용하여 PH15-7-MO 스테인리스강과 같은 고강도 합금을 절단할 수 있는 극초음속 액체 제트를 공급했다. 마하 3 북미 XB-70 발키리에 대한 벌집 적층체를 절단하기 위해 사용된 이 절단 방법은 고속 박리를 초래하여 제조 공정에 변화가 필요했다.[6]

XB-70 프로젝트에 효과적이지는 않았지만, 이 개념은 유효했고 워터젯 절삭을 발전시키기 위한 추가 연구가 계속되었다. 1962년 유니언 카바이드(Union Carbide)사의 필립 라이스(Philip Rice)는 금속, 석재 및 기타 물질을 절단하기 위해 최대 50,000 psi(340 MPa)의 펄스인 워터 제트를 사용하여 탐구했다.[7] Research by S.J. Leach and G.L. Walker in the mid-1960s expanded on traditional coal waterjet cutting to determine ideal nozzle shape for high-pressure waterjet cutting of stone,[8] and Norman Franz in the late 1960s focused on waterjet cutting of soft materials by dissolving long chain polymers in the water to improve the cohesiveness of the jet stream.[9] In the early 1970s, the desire to improve the durability of the waterjet nozzle led Ray Chadwick, Michael Kurko, and Joseph Corriveau of the Bendix Corporation to come up with the idea of using corundum crystal to form a waterjet orifice,[10] while Norman Franz expanded on this and created a waterjet nozzle with an orifice as small as 0.002 인치 (0.051 mm) that operated at pressures up to 70,000 psi (480 MPa).[11] John Olsen, along with George Hurlburt and Louis Kapcsandy at Flow Research (later Flow Industries), further improved the commercial potential of the waterjet by showing that treating the water beforehand could increase the operational life of the nozzle.[12]

고압

편집High-pressure vessels and pumps became affordable and reliable with the advent of steam power. By the mid-1800s, steam locomotives were common and the first efficient steam-driven fire engine was operational.[13] By the turn of the century, high-pressure reliability improved, with locomotive research leading to a sixfold increase in boiler pressure, some reaching 1,600 psi (11 MPa). Most high-pressure pumps at this time, though, operated around 500–800 psi (3.4–5.5 MPa).

High-pressure systems were further shaped by the aviation, automotive, and oil industries. Aircraft manufacturers such as Boeing developed seals for hydraulically boosted control systems in the 1940s,[14] while automotive designers followed similar research for hydraulic suspension systems.[15] Higher pressures in hydraulic systems in the oil industry also led to the development of advanced seals and packing to prevent leaks.[16]

These advances in seal technology, plus the rise of plastics in the post-war years, led to the development of the first reliable high-pressure pump. The invention of Marlex by Robert Banks and John Paul Hogan of the Phillips Petroleum Company required a catalyst to be injected into the polyethylene.[17] McCartney Manufacturing Company in Baxter Springs, Kansas, began manufacturing these high-pressure pumps in 1960 for the polyethylene industry.[18] Flow Industries in Kent, Washington set the groundwork for commercial viability of waterjets with John Olsen’s development of the high-pressure fluid intensifier in 1973,[19] a design that was further refined in 1976.[20] Flow Industries then combined the high-pressure pump research with their waterjet nozzle research and brought waterjet cutting into the manufacturing world.[출처 필요]

연마재 워터젯 (Abrasive waterjet)

편집부드러운 소재는 물로 절삭하는 것이 가능하지만, 연마재가 추가됨에 따라 워터젯은 모든 소재에 대한 현대적인 가공 도구가 되었다. 이것은 1935년 엘모 스미스(Elmo Smith)가 액체 연마재 발파를 위해 물줄기에 연마재를 추가하는 아이디어를 개발하면서 시작되었다.[21] 스미스의 디자인은 1937년 하이드로블라스트 코퍼레이션(Hydroblast Corporation)의 레슬리 티렐(Leslie Tirrell)에 의해 더욱 다듬어졌으며, 노즐 디자인은 습식 발파를 위해 고압수와 연마재를 혼합한 것이었다.[22]

The first publications on modern abrasive waterjet (AWJ) cutting were published by Mohamed Hashish in the 1982 BHR proceedings showing, for the first time, that waterjets with relatively small amounts of abrasives are capable of cutting hard materials such as steel and concrete. The March 1984 issue of the Mechanical Engineering magazine showed more details and materials cut with AWJ such as titanium, aluminium, glass, and stone. Mohamed Hashish was awarded a patent on forming AWJ in 1987.[23] Hashish, who also coined the new term abrasive waterjet, and his team continued to develop and improve the AWJ technology and its hardware for many applications which is now in over 50 industries worldwide. A critical development was creating a durable mixing tube that could withstand the power of the high-pressure AWJ, and it was Boride Products (now Kennametal) development of their ROCTEC line of ceramic tungsten carbide composite tubes that significantly increased the operational life of the AWJ nozzle.[24] Current work on AWJ nozzles is on micro abrasive waterjets so that cutting with jets smaller than 0.015 인치 (0.38 mm) in diameter can be commercialized.

Working with Ingersoll-Rand Waterjet Systems, Michael Dixon implemented the first production practical means of cutting titanium sheets—an abrasive waterjet system very similar to those in widespread use today.[23] By January 1989, that system was being run 24 hours a day producing titanium parts for the B-1B largely at Rockwell's North American Aviation facility in Newark, Ohio.

오늘날에는 두 가지 유형의 연마 워터젯이 있다,

연마수 서스펜션 제트 절단 (Abrasive Water Suspension Jet, AWSJ)

편집The Abrasive Water Suspension Jet (AWSJ) - often called “Slurry Jet” or “Water Abrasive Suspension (WAS) jet” - is a specific type of abrasive water jet, which is used for waterjet cutting. In contrast to the abrasive water injector jet (AWIJ), the abrasive water suspension jet (AWSJ)[25] is characterised by the fact that the mixing of abrasive and water takes place before the nozzle. This has the effect that, in contrast to AWIJ, the jet consists of only two components (water - abrasive).

Since there are only 2 components (water and abrasive) in the AWSJ, the acceleration of the abrasive grains by the water takes place with a significantly increased efficiency compared to the AWIJ.[26] The abrasive grains become faster with the WASS than with the WAIS for the same hydraulic power of the system. Therefore, comparatively deeper or faster cuts can be made with the AWSJ.

AWSJ cutting, in contrast to the AWIJ cutting process described below, can also be used for mobile cutting applications and cutting under water, in addition to machining demanding materials.[27][28][25] Examples include bomb disposal[29] s well as the dismantling of offshore installations[30] or the dismantling of reactor pressure vessel installations in nuclear power plants.[31]

연마수 분사기 절단(Abrasive Water Injector Jet, AWIJ)

편집The AWIJ[32] is generated by a water jet that passes through a mixing chamber (a cavity) after exiting the water nozzle and enters a focusing tube at the exit of the mixing chamber. The interaction of the water jet in the mixing chamber with the air inside creates negative pressure, the water jet entrains air particles. This negative pressure is used for the pneumatic transport of the abrasive into the chamber (the abrasive is led to a lateral opening (bore) of the mixing chamber by means of a hose).

After contact with the abrasive material in the mixing chamber with the water jet, the individual abrasive grains are accelerated and entrained in the direction of the focusing tube. The air used as a carrier medium for transporting the abrasive into the mixing chamber also becomes part of the AWIJ, which now consists of three components (water - abrasive - air). In the focusing tube, which is (should be) optimised in its length for this purpose, the abrasive is further accelerated (energy transfer from the water to the abrasive grain) and the AWIJ ideally leaves the focusing tube at the maximum possible abrasive grain speed.

워터젯 제어

편집As waterjet cutting moved into traditional manufacturing shops, controlling the cutter reliably and accurately was essential. Early waterjet cutting systems adapted traditional systems such as mechanical pantographs and CNC systems based on John Parsons’ 1952 NC milling machine and running G-code.[33] Challenges inherent to waterjet technology revealed the inadequacies of traditional G-Code, as to accuracy, depends on varying the speed of the nozzle as it approaches corners and details.[34] Creating motion control systems to incorporate those variables became a major innovation for leading waterjet manufacturers in the early 1990s, with John Olsen of OMAX Corporation developing systems to precisely position the waterjet nozzle[35] while accurately specifying the speed at every point along the path,[36] and also utilizing common PCs as a controller. The largest waterjet manufacturer, Flow International (a spinoff of Flow Industries), recognized the benefits of that system and licensed the OMAX software, with the result that the vast majority of waterjet cutting machines worldwide are simple to use, fast, and accurate.[37]

작동

편집All waterjets follow the same principle of using high pressure water focused into a beam by a nozzle. Most machines accomplish this by first running the water through a high pressure pump. There are two types of pumps used to create this high pressure; an intensifier pump and a direct drive or crankshaft pump. A direct drive pump works much like a car engine, forcing water through high pressure tubing using plungers attached to a crankshaft. An intensifier pump creates pressure by using hydraulic oil to move a piston forcing the water through a tiny hole.[38][39] The water then travels along the high pressure tubing to the nozzle of the waterjet. In the nozzle, the water is focused into a thin beam by a jewel orifice. This beam of water is ejected from the nozzle, cutting through the material by spraying it with the jet of speed on the order of Mach 3, around 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s).[40] The process is the same for abrasive waterjets until the water reaches the nozzle. Here abrasives such as garnet and aluminium oxide, are fed into the nozzle via an abrasive inlet. The abrasive then mixes with the water in a mixing tube and is forced out the end at high pressure.[41][42]

이익

편집An important benefit of the water jet is the ability to cut material without interfering with its inherent structure, as there is no heat-affected zone (HAZ). Minimizing the effects of heat allows metals to be cut without warping, affecting tempers, or changing intrinsic properties.[43] Sharp corners, bevels, pierce holes, and shapes with minimal inner radii are all possible.[44]

Water jet cutters are also capable of producing intricate cuts in material. With specialized software and 3-D machining heads, complex shapes can be produced.[45]

The kerf, or width, of the cut can be adjusted by swapping parts in the nozzle, as well as changing the type and size of abrasive. Typical abrasive cuts have a kerf in the range of 0.04 to 0.05 in (1.0–1.3 mm), but can be as narrow as 0.02 인치 (0.51 mm). Non-abrasive cuts are normally 0.007 to 0.013 in (0.18–0.33 mm), but can be as small as 0.003 인치 (0.076 mm), which is approximately that of a human hair. These small jets can permit small details in a wide range of applications.

Water jets are capable of attaining accuracy down to 0.005 인치 (0.13 mm) and repeatability down to 0.001 인치 (0.025 mm).[45]

Due to its Versatility narrow kerf, water jet cutting can reduce the amount of scrap material produced, by allowing uncut parts to be nested more closely together than traditional cutting methods. Water jets use approximately 0.5 to 1 US gal (1.9–3.8 l) per minute (depending on the cutting head's orifice size), and the water can be recycled using a closed-loop system. Waste water usually is clean enough to filter and dispose of down a drain. The garnet abrasive is a non-toxic material that can be mostly recycled for repeated use; otherwise, it can usually be disposed of in a landfill. Water jets also produce fewer airborne dust particles, smoke, fumes, and contaminants,[45] reducing operator exposure to hazardous materials.[46]

Meatcutting using waterjet technology eliminates the risk of cross contamination since the contact medium is discarded.

다기능성

편집Because the nature of the cutting stream can be easily modified the water jet can be used in nearly every industry; there are many different materials that the water jet can cut. Some of them have unique characteristics that require special attention when cutting.

Materials commonly cut with a water jet include textiles, rubber, foam, plastics, leather, composites, stone, tile, glass, metals, food, paper and much more.[47] "Most ceramics can also be cut on an abrasive water jet as long as the material is softer than the abrasive being used (between 7.5 and 8.5 on the Mohs scale)".[48] Examples of materials that cannot be cut with a water jet are tempered glass and diamonds.[46] Water jets are capable of cutting up to 6 in (150 mm) of metals and 18 in (460 mm) of most materials,[49] though in specialized coal mining applications,[50] water jets are capable of cutting up to 100 ft (30 m) using a 1 in (25 mm) nozzle.[51]

Specially designed water jet cutters are commonly used to remove excess bitumen from road surfaces that have become the subject of binder flushing. Flushing is a natural occurrence caused during hot weather where the aggregate becomes level with the bituminous binder layer creating a hazardously smooth road surface during wet weather.

유용성

편집상업용 워터 제트 절삭 시스템은 다양한 크기의 전 세계 제조업체에서 사용할 수 있으며 압력 범위가 가능한 워터 펌프를 갖추고 있다. 일반적인 워터젯 절단기는 몇 평방 피트 또는 수백 평방 피트의 작은 작업 봉투를 가지고 있다. 초고압 워터 펌프는 최저 40,000psi(280 MPa)에서 최대 100,000psi(690 MPa)까지 사용할 수 있다.[45]

절단 과정

편집워터젯 절단에는 아래와 같은 6가지의 주요 공정 과정이 있다.

- 고압 펌프에 의해 생성되는 30,000–90,000 psi(210–620 MPa)의 초고속 스트림을 사용하며, 이 스트림에 연마성 입자가 부유할 수 있다.

- 워터젯은 감열성, 섬세성 또는 매우 단단한 재료를 포함한 다양한 재료를 가공하는 데 사용된다.

- 공작물 표면 또는 가장자리에 열 손상이 발생하지 않는다.

- 노즐은 일반적으로 소결 붕화물 또는 복합 텅스텐 탄화물로 만들어진다.[52]

- 대부분의 절단에서 1도 미만의 테이퍼를 생성하며, 절단 프로세스를 늦추거나 제트를 기울임으로써 완전히 줄이거나 제거할 수 있다.[53]

- 공작물로부터의 노즐의 거리는 커프(Curf)의 크기와 재료의 제거율에 영향을 미친다. 일반적인 거리는 3.2 mm (125 인치) 이다.

온도는 그다지 중요한 요소가 아니다.

가장자리 품질

편집워터 제트 절단 부품의 가장자리 품질은 품질 번호 Q1 ~ Q5로 정의된다. 숫자가 작을수록 가장자리가 거칠어짐을 나타내며, 커질수록 부드러워짐을 나타낸다. 얇은 소재의 경우 Q1의 커팅 속도 차이가 Q5의 속도보다 최대 3배 이상 빨라질 수 있다. 두꺼운 소재의 경우 Q1이 Q5보다 6배 빠를 수 있다. 예를 들어, 4μm(100mm) 두께의 알루미늄 Q5는 0.72인치(18mm/μ)이고 Q1은 4.2인치(110mm/μ)로 5.8배 빠르다.[54]

다축 절단 (Multi-axis cutting)

편집1987년 잉거솔랜드 워터젯 시스템(Ingersoll-Rand Waterjet Systems)은 로봇 워터젯 시스템(Robotic Waterjet System)이라고 불리는 5축 순수 워터젯 절단 시스템을 제공했다. 이 시스템은 HS-1000과 비슷한 오버헤드 갠트리 설계였다.

With recent advances in control and motion technology, 5-axis water jet cutting (abrasive and pure) has become a reality. Where the normal axes on a water jet are named Y (back/forth), X (left/right) and Z (up/down), a 5-axis system will typically add an A axis (angle from perpendicular) and C axis (rotation around the Z-axis). Depending on the cutting head, the maximum cutting angle for the A axis can be anywhere from 55, 60, or in some cases even 90 degrees from vertical. As such, 5-axis cutting opens up a wide range of applications that can be machined on a water jet cutting machine.

A 5-axis cutting head can be used to cut 4-axis parts, where the bottom surface geometries are shifted a certain amount to produce the appropriate angle and the Z-axis remains at one height. This can be useful for applications like weld preparation where a bevel angle needs to be cut on all sides of a part that will later be welded, or for taper compensation purposes where the kerf angle is transferred to the waste material – thus eliminating the taper commonly found on water jet-cut parts. A 5-axis head can cut parts where the Z-axis is also moving along with all the other axes. This full 5-axis cutting could be used for cutting contours on various surfaces of formed parts.

Because of the angles that can be cut, part programs may need to have additional cuts to free the part from the sheet. Attempting to slide a complex part at a severe angle from a plate can be difficult without appropriate relief cuts.

같이 보기

편집- 크라이제트 (CryoJet)

- 레이저 절단 (Laser cutting)

- 플라즈마 절단 (Plasma cutting)

- 방전 가공 (Electrical discharge machining)

각주

편집- ↑ 《About waterjets》, 2010년 2월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서, 2010년 2월 13일에 확인함.

- ↑ Guidorzi, Elia (2022년 2월 3일). “Waterjet Cutting History - Origins of the Waterjet Cutter”. 《TechniWaterjet》 (미국 영어). 2022년 2월 17일에 확인함.

- ↑ Fourness, Charles A et al, Paper Metering, Cutting, and Reeling 보관됨 2014-02-19 - 웨이백 머신, filed May 22, 1933, and issued July 2, 1935.

- ↑ Johnson, Carl Olof, Method for Cutting Up Plastic and Semi-Plastic Masses 보관됨 2014-01-30 - 웨이백 머신, filed March 13, 1956, and issued April 14, 1959.

- ↑ Schwacha, Billie G., Liquid Cutting of Hard Metals 보관됨 2014-01-30 - 웨이백 머신, filed October 13, 1958, and issued May 23, 1961.

- ↑ Jenkins, Dennis R & Tony R Landis, Valkyrie: North American's Mach 3 Superbomber, Specialty Press, 2004, p. 108.

- ↑ Rice, Phillip K., Process for Cutting and Working Solid Materials 보관됨 2014-01-31 - 웨이백 머신, filed October 26, 1962, and issued October 19, 1965.

- ↑ Leach, S.J. and G.L. Walker, The Application of High Speed Liquid Jets to Cutting, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, Vol 260, No 1110, July 28, 1966, pp. 295–310.

- ↑ Franz, Norman C., High Velocity Liquid Jet 보관됨 2014-01-31 - 웨이백 머신, filed May 31, 1968, and issued August 18, 1970.

- ↑ Chadwick, Ray F Chadwick, Michael C Kurko, and Joseph A Corriveau, Nozzle for Producing Fluid Cutting Jet 보관됨 2014-01-31 - 웨이백 머신, filed March 1, 1971, and issued September 4, 1973.

- ↑ Franz, Norman C., Very High Velocity Fluid Jet Nozzles and Methods of Making Same 보관됨 2014-01-31 - 웨이백 머신, filed July 16, 1971, and issued August 7, 1973.

- ↑ Olsen, John H., George H. Hurlburt, and Louis E. Kapcsandy, Method for Making High Velocity Liquid Jet 보관됨 2014-01-31 - 웨이백 머신, filed June 21, 1976, and issued August 12, 1980.

- ↑ “John Ericsson”. 《British Made Steam Fire Engines》. 2012년 3월 28일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 6월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Berry, Mitchell M., Piston Sealing Assembly 보관됨 2014-03-05 - 웨이백 머신, filed March 3, 1941, and issued March 23, 1943.

- ↑ Templeton, Herbert W., Metering Valve Seal 보관됨 2014-03-05 - 웨이백 머신, filed July 11, 1958, and issued July 18, 1961.

- ↑ Webb, Derrel D., High Pressure Packing Means 보관됨 2014-03-05 - 웨이백 머신, filed August 12, 1957, and issued October 17, 1961.

- ↑ Hogan, John Paul and Robert L. Banks, Polymers and Production Thereof 보관됨 2015-07-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed March 26, 1956, and issued March 4, 1958.

- ↑ “KMT McCartney Products for the LDPE Industry”. KMT McCartney Products. 2012년 12월 24일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 6월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Olsen, John H., High Pressure Fluid Intensifier and Method 보관됨 2015-07-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed January 12, 1973, and issued May 21, 1974.

- ↑ Olsen, John H., High Pressure Fluid Intensifier and Method 보관됨 2015-07-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed March 16, 1976, and issued June 14, 1977.

- ↑ Smith, Elmo V., Liquid Blasting 보관됨 2014-02-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed June 10, 1935, and issued May 12, 1936.

- ↑ Tirrell, Leslie L., Sandblast Device 보관됨 2014-02-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed April 3, 1937, and issued October 17, 1939.

- ↑ 가 나 Hashish, Mohamed, Michael Kirby and Yih-Ho Pao, Method and Apparatus for Forming a High Velocity Liquid Abrasive Jet 보관됨 2014-02-27 - 웨이백 머신, filed October 7, 1985, and issued March 10, 1987.

- ↑ “ROCTEC Composite Carbide Abrasive Waterjet Nozzles” (PDF). Kennametal Boride Abrasive Flow Products. 2008년 12월 6일에 원본 문서 (PDF)에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 7월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ 가 나 “Wasser-Abrasiv-Suspensions-Strahl-schneiden (WASS) – Institut für Werkstoffkunde” (독일어).

- ↑ “Measurement and Analysis of Abrasive Particles Velocities in AWSJ”, 《Procedia Engineering》 (독일어) 149, 2016년 1월 1일, pp. 77–86, doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.06.641, ISSN 1877-7058, 2021년 7월 1일에 확인함

- ↑ Pressestelle. “Hochleistungsverfahren bezwingt Hochleistungswerkstoffe” (독일어).

- ↑ Prof. Dr.-Ing.Michael Kaufeld, Prof. Dr.-Ing. Frank Pude, Dipl.-ing. Marco Linde (March 2019). “ConSus – DAs Wasser-Abrasiv-Suspensionstrahl-System mit kontinuierlicher Abrasivmittelzufuhr” (PDF). 《https://studium.hs-ulm.de/de/users/625229/Documents/Ingenieurspiegel%20ConSus_IS_3_2019.pdf》 (독일어). Ingenieur-Spiegel. Band 3-2019. Public Verlagsgesellschaft und Anzeigenagentur mbH, Bingen, S. 23–25.

|periodical=에 외부 링크가 있음 (도움말) - ↑ NDR. “Bombenentschärfungen: Neue Wasserstrahl-Technik” (독일어).

- ↑ “Decommissioning Project Completed for Middle East Offshore Platform”.

- ↑ “Spektakulärer Robotereinsatz: Stäublis Unterwasser-Roboter zerlegt radioaktive AKW-Bestandteile” (독일어). 2021년 1월 7일.

- ↑ “Wasser-Abrasiv-Injektor-Strahl-schneiden (WAIS) – Institut für Werkstoffkunde” (독일어).

- ↑ “Machining & CNC Manufacturing: A brief history”. Worcester Polytechnic Institute. 2004년 8월 20일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 6월 25일에 확인함.

- ↑ Olsen, John H. “What Really Determines the Time to Make a Part?”. 《Dr Olsen's Lab》. 2012년 5월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 6월 28일에 확인함.

- ↑ Olsen, John H., Motion Control for Quality in Jet Cutting 보관됨 2014-02-28 - 웨이백 머신, filed May 14, 1997, and issued April 6, 1999.

- ↑ Olsen, John H., Motion Control with Precomputation 보관됨 2014-02-28 - 웨이백 머신, filed October 7, 1993, and issued April 16, 1996.

- ↑ “SEC Form 8-K”. Flow International Corporation. 2013년 12월 12일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2012년 7월 1일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Crankshaft vs. Intensifier pump”. 《WaterJets.org》. Olsen Software LLC. 2016년 8월 6일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Types of Pumps”. 《www.wardjet.com》. 2016년 6월 17일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “2.972 How an Abrasive Waterjet Cutter Works”. 《web.mit.edu》.

- ↑ “Basic Waterjet Principles”. 《WaterJets.org》. Olsen Software LLC. 2010년 2월 26일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “How Does a Waterjet Work?”. 《OMAX Abrasive Waterjets》. 2016년 6월 2일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ Lorincz, Jim. Waterjets: Evolving from Macro to Micro, Manufacturing Engineering, Society of Manufacturing Engineers, November, 2009

- ↑ “Waterjet Cutting Advantages”. 2017년 9월 21일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 Lorincz, Waterjets: Evolving from Macro to Micro.

- ↑ 가 나 “Company”. Jet Edge. 2009년 2월 23일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2009년 6월 11일에 확인함.

- ↑ “What is a Waterjet cutting machine ?”. 《Thibaut》 (영어). 2020년 11월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ “What Materials Can a Waterjet Cut?”. 《OMAX Abrasive Waterjets》. 2016년 6월 2일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2016년 6월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Waterjet Cutting - Cut Metal, Stone, Paper, Composites”. 《www.kmt-waterjet.com》. 2017년 4월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

- ↑ “What is a Waterjet cutting machine ?”. 《Thibaut》 (영어). 2019년 10월 14일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Archived copy”. 2017년 5월 5일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 9월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ WARDJet. “Waterjet University - Precision and Quality”. 《WARDJet》 (미국 영어). 2017년 2월 11일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2017년 2월 10일에 확인함.

- ↑ Olsen, John. “Improving waterjet cutting precision by eliminating taper”. 《TheFabricator.com》. FMA Communications. 2015년 7월 22일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2015년 7월 18일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Waterjet Relationship Parameters”. 2010년 9월 9일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서.

외부 링크

편집- 워터젯의 작동 방식, HowStuffWorks.com 영상

- 워터젯 절삭기에 의한 직물 절삭

- 워터젯 절단 – 작동 방식, 워터젯 절삭에 사용되는 고압수 달성을 위한 물리학적 고찰

- 워터젯 절단기란 무엇인가?, 과정의 정의

- 워터젯 절삭의 역사에 있어서의 이정표