사용자:배우는사람/문서:Serpent

Serpent (symbolism) 편집

The serpent, or snake, is one of the oldest and most widespread mythological symbols. The word is derived from Latin serpens, a crawling animal or snake. Snakes have been associated with some of the oldest rituals known to humankind[1] and represent dual expression[2] of good and evil.[3]

In some cultures snakes were fertility symbols, for example the Hopi people of North America performed an annual snake dance to celebrate the union of Snake Youth (a Sky spirit) and Snake Girl (an Underworld spirit) and to renew fertility of Nature. During the dance, live snakes were handled and at the end of the dance the snakes were released into the fields to guarantee good crops. "The snake dance is a prayer to the spirits of the clouds, the thunder and the lightning, that the rain may fall on the growing crops.."[4] In other cultures snakes symbolized the umbilical cord, joining all humans to Mother Earth. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars - sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete - and they were worshiped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration.[5]

Symbolic values frequently assigned to serpents 편집

Fertility and rebirth 편집

Historically, serpents and snakes represent fertility or a creative life force. As snakes shed their skin through sloughing, they are symbols of rebirth, transformation, immortality, and healing.[6] The ouroboros is a symbol of eternity and continual renewal of life.

In the Abrahamic religions, the serpent represents sexual desire.[7] According to the Rabbinical tradition, in the Garden of Eden, the serpent represents sexual passion.[8] In Hinduism, Kundalini is a coiled serpent, the residual power of pure desire.[9]

Guardianship 편집

Serpents are represented as potent guardians of temples and other sacred spaces. This connection may be grounded in the observation that when threatened, some snakes (such as rattlesnakes or cobras) frequently hold and defend their ground, first resorting to threatening display and then fighting, rather than retreat. Thus, they are natural guardians of treasures or sacred sites which cannot easily be moved out of harm's way.

At Angkor in Cambodia, numerous stone sculptures present hooded multi-headed nāgas as guardians of temples or other premises. A favorite motif of Angkorean sculptors from approximately the 12th century CE onward was that of the Buddha, sitting in the position of meditation, his weight supported by the coils of a multi-headed naga that also uses its flared hood to shield him from above. This motif recalls the story of the Buddha and the serpent king Mucalinda: as the Buddha sat beneath a tree engrossed in meditation, Mucalinda came up from the roots of the tree to shield the Buddha from a tempest that was just beginning to arise.

The Gadsden flag of the American Revolution depicts a rattlesnake coiled up and poised to strike. Below the image of the snake is the legend, "Don't tread on me." The snake symbolized the dangerousness of colonists willing to fight for their rights and homeland. The motif is repeated in the First Navy Jack of the US Navy.

Poison and medicine 편집

Serpents are connected with poison and medicine. The snake's venom is associated with the chemicals of plants and fungi[10][11][12] that have the power to either heal, poison or provide expanded consciousness (and even the elixir of life and immortality) through divine intoxication. Because of its herbal knowledge and entheogenic association the snake was often considered one of the wisest animals, being (close to the) divine. Its divine aspect combined with its habitat in the earth between the roots of plants made it an animal with chthonic properties connected to the afterlife and immortality. Asclepius, the God of medicine and healing, carried a staff with one serpent wrapped around it, which has become the symbol of modern medicine.

Vengefulness and vindictiveness 편집

Serpents are connected with vengefulness and vindictiveness. This connection depends in part on the experience that venomous snakes often deliver deadly defensive bites without giving prior notice or warning to their unwitting victims. Although a snake is defending itself from the encroachment of its victim into the snake's immediate vicinity, the unannounced and deadly strike may seem unduly vengeful when measured against the unwitting victim's perceived lack of blameworthiness.

Edgar Allan Poe's famous short story "The Cask of Amontillado" invokes the image of the serpent as a symbol for petty vengefulness. The story is told from the point of view of the vindictive Montresor, who hatches a secret plot to murder his rival Fortunato in order to avenge real or imagined insults. Before carrying out his scheme, Montresor reveals his family's coat-of-arms to the intended victim: "A huge human foot d'or, in a field azure; the foot crushes a serpent rampant whose fangs are imbedded in the heel." Fortunato, not suspecting that he has offended Montresor, fails to understand the symbolic import of the coat-of-arms, and blunders onward into Montresor's trap.

Mythological serpents 편집

Dragons 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

Occasionally, serpents and dragons are used interchangeably, having similar symbolic functions. The venom of the serpent is thought to have a fiery quality similar to a fire spitting dragon. The Greek Ladon and the Norse Níðhöggr (Nidhogg Nagar) are sometimes described as serpents and sometimes as dragons. In Germanic mythology, serpent (Old English: wyrm, Old High German: wurm, Old Norse: ormr) is used interchangeably with the Greek borrowing dragon (OE: draca, OHG: trahho, ON: dreki). In China and especially in Indochina, the Indian serpent nāga was equated with the lóng or Chinese dragon. The Aztec and Toltec serpent god Quetzalcoatl also has dragon like wings, like its equivalent in K'iche' Maya mythology Q'uq'umatz ("feathered serpent").

Sea serpents 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

Sea serpents were giant cryptozoological creatures once believed to live in water, whether sea monsters such as the Leviathan or lake monsters such as the Loch Ness Monster. If they were referred to as "sea snakes", they were understood to be the actual snakes that live in Indo-Pacific waters (Family Hydrophiidae).

Cosmic serpents 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

The serpent, when forming a ring with its tail in its mouth, is a clear and widespread symbol of the "All-in-All", the totality of existence, infinity and the cyclic nature of the cosmos. The most well known version of this is the Aegypto-Greek Ourobouros. It is believed to have been inspired by the Milky Way, as some ancient texts refer to a serpent of light residing in the heavens. The Ancient Egyptians associated it with Wadjet, one of their oldest deities as well as another aspect, Hathor. In Norse mythology the World Serpent (or Midgard serpent) known as Jörmungandr encircled the world in the ocean's abyss biting its own tail.

In Hindu mythology Lord Vishnu is said to sleep while floating on the cosmic waters on the serpent Shesha. In the Puranas Shesha holds all the planets of the universe on his hoods and constantly sings the glories of Vishnu from all his mouths. He is sometimes referred to as "Ananta-Shesha," which means "Endless Shesha". In the Samudra manthan chapter of the Puranas, Shesha loosens Mount Mandara for it to be used as a churning rod by the Asuras and Devas to churn the ocean of milk in the heavens in order to make Soma (or Amrita), the divine elixir of immortality. As a churning rope another giant serpent called Vasuki is used.

In pre-Columbian Central America Quetzalcoatl was sometimes depicted as biting its own tail. The mother of Quetzalcoatl was the Aztec goddess Coatlicue ("the one with the skirt of serpents"), also known as Cihuacoatl ("The Lady of the serpent"). Quetzalcoatl's father was Mixcoatl ("Cloud Serpent"). He was identified with the Milky Way, the stars and the heavens in several Mesoamerican cultures.

The demigod Aidophedo of the West African Ashanti is also a serpent biting its own tail. In Dahomey mythology of Benin in West Africa, the serpent that supports everything on its many coils was named Dan. In the Vodou of Benin and Haiti Ayida-Weddo (a.k.a. Aida-Wedo, Aido Quedo, "Rainbow-Serpent") is a spirit of fertility, rainbows and snakes, and a companion or wife to Dan, the father of all spirits. As Vodou was exported to Haiti through the slave trade Dan became Danballah, Damballah or Damballah-Wedo. Because of his association with snakes, he is sometimes disguised as Moses, who carried a snake on his staff. He is also thought by many to be the same entity of Saint Patrick, known as a snake banisher.

The serpent Hydra is a star constellation representing either the serpent thrown angrily into the sky by Apollo or the Lernaean Hydra as defeated by Heracles for one of his Twelve Labors. The constellation Serpens represents a snake being tamed by Ophiuchus the snake-handler, another constellation. The most probable interpretation is that Ophiuchus represents the healer Asclepius.

Chthonic serpents and sacred trees 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

Under yet another Tree (the Bodhi tree of Enlightenment), the Buddha sat in ecstatic meditation. When a storm arose, the mighty serpent king Mucalinda rose up from his place beneath the earth and enveloped the Buddha in seven coils for seven days, not to break his ecstatic state.

The Vision Serpent was also a symbol of rebirth in Mayan mythology, fueling some cross-Atlantic cultural contexts favored in pseudoarchaeology. The Vision Serpent goes back to earlier Maya conceptions, and lies at the center of the world as the Mayans conceived it. "It is in the center axis atop the World Tree. Essentially the World Tree and the Vision Serpent, representing the king, created the center axis which communicates between the spiritual and the earthly worlds or planes. It is through ritual that the king could bring the center axis into existence in the temples and create a doorway to the spiritual world, and with it power". (Schele and Friedel, 1990: 68)

Sometimes the Tree of Life is represented (in a combination with similar concepts such as the World Tree and Axis mundi or "World Axis") by a staff such as those used by shamans. Examples of such staffs featuring coiled snakes in mythology are the caduceus of Hermes, the Rod of Asclepius, the staff of Moses, and the papyrus reeds and deity poles entwined by a single serpent Wadjet, dating to earlier than 3000 BCE. The oldest known representation of two snakes entwined around a rod is that of the Sumerian fertility god Ningizzida. Ningizzida was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head, eventually becoming a god of healing and magic. It is the companion of Dumuzi (Tammuz) with whom it stood at the gate of heaven. In the Louvre, there is a famous green steatite vase carved for King Gudea of Lagash (dated variously 2200–2025 BCE) with an inscription dedicated to Ningizzida. Ningizzida was the ancestor of Gilgamesh, who according to the epic dived to the bottom of the waters to retrieve the plant of life. But while he rested from his labor, a serpent came and ate the plant. The snake became immortal, and Gilgamesh was destined to die.

Ningizzida has been popularized in the 20th century by Raku Kei Reiki (a.k.a. "The Way of the Fire Dragon") where "Nin Giz Zida" is believed to be a fire serpent of Tibetan rather than Sumerian origin. Nin Giz Zida is another name for the ancient Hindu concept of Kundalini, a Sanskrit word meaning either "coiled up" or "coiling like a snake". Kundalini refers to the mothering intelligence behind yogic awakening and spiritual maturation leading to altered states of consciousness. There are a number of other translations of the term usually emphasizing a more serpentine nature to the word—e.g. 'serpent power'. It has been suggested by Joseph Campbell that the symbol of snakes coiled around a staff is an ancient representation of Kundalini physiology. The staff represents the spinal column with the snake(s) being energy channels. In the case of two coiled snakes they usually cross each other seven times, a possible reference to the seven energy centers called chakras.

In Ancient Egypt, where the earliest written cultural records exist, the serpent appears from the beginning to the end of their mythology. Ra and Atum ("he who completes or perfects") became the same god, Atum, the "counter-Ra," was associated with earth animals, including the serpent: Nehebkau ("he who harnesses the souls") was the two headed serpent deity who guarded the entrance to the underworld. He is often seen as the son of the snake goddess Renenutet. She often was confused with (and later was absorbed by) their primal snake goddess Wadjet, the Egyptian cobra, who from the earliest of records was the patron and protector of the country, all other deities, and the pharaohs. Hers is the first known oracle. She was depicted as the crown of Egypt, entwined around the staff of papyrus and the pole that indicated the status of all other deities, as well as having the all-seeing eye of wisdom and vengeance. She never lost her position in the Egyptian pantheon.

The image of the serpent as the embodiment of the wisdom transmitted by Sophia was an emblem used by gnosticism, especially those sects that the more orthodox characterized as "Ophites" ("Serpent People"). The chthonic serpent was one of the earth-animals associated with the cult of Mithras. The Basilisk, the venomous "king of serpents" with the glance that kills, was hatched by a serpent, Pliny the Elder and others thought, from the egg of a cock.

Outside Eurasia, in Yoruba mythology, Oshunmare was another mythic regenerating serpent.

The Rainbow Serpent (also known as the Rainbow Snake) is a major mythological being for Aboriginal people across Australia, although the creation myth associated with it are best known from northern Australia. In Fiji Ratumaibulu was a serpent god who ruled the underworld and made fruit trees bloom.

Nagas 편집

Naga (Sanskrit:नाग) is the Sanskrit/Pāli word for a deity or class of entity or being, taking the form of a very large snake, found in Hinduism and Buddhism. The naga primarily represents rebirth, death and mortality, due to its casting of its skin and being symbolically "reborn".

Brahmins associated naga with Shiva and with Vishnu, who rested on a 100 headed naga coiled around Shiva’s neck. The snake represented freedom in Hindu mythology because they cannot be tamed.

Nagas of Indochina 편집

Serpents, or nāgas, play a particularly important role in Cambodian, Isan and Laotian mythology. An origin myth explains the emergence of the name "Cambodia" as resulting from conquest of a naga princess by a Kambuja lord named Kaundinya: the descendants of their union are the Khmer people.[13] George Coedès suggests the Cambodian myth is a basis for the legend of "Phra Daeng Nang Ai", in which a woman who has lived many previous lives in the region is reincarnated as a daughter of Phraya Khom (Thai for Cambodian,) and causes the death of her companion in former lives who has been reincarnated as a prince of the Nagas. This leads to war between the "spirits of the air" and the Nagas: Nagas amok are rivers in spate, and the entire region is flooded.[14] The Myth of the Toad King tells how introduction of Buddhist teachings led to war with the sky deity Phaya Thaen, and ended in a truce with nagas posted as guardians of entrances to temples.[15]

Greek mythology 편집

The Minoan Snake Goddess brandished a serpent in either hand, perhaps evoking her role as source of wisdom, rather than her role as Mistress of the Animals (Potnia theron), with a leopard under each arm.

Serpents figured prominently in archaic Greek myths. According to some sources, Ophion ("serpent", a.k.a. Ophioneus), ruled the world with Eurynome before the two of them were cast down by Cronus and Rhea. The oracles of the Ancient Greeks were said to have been the continuation of the tradition begun with the worship of the Egyptian cobra goddess, Wadjet.

Typhon the enemy of the Olympian gods is described as a vast grisly monster with a hundred heads and a hundred serpents issuing from his thighs, who was conquered and cast into Tartarus by Zeus, or confined beneath volcanic regions, where he is the cause of eruptions. Typhon is thus the chthonic figuration of volcanic forces. Serpent elements figure among his offspring; among his children by Echidna are: Cerberus (a monstrous three-headed dog with a snake for a tail and a serpentine mane); the serpent-tailed Chimaera; the serpent-like chthonic water beast Lernaean Hydra; and the hundred-headed serpentine dragon Ladon. Both the Lernaean Hydra and Ladon were slain by Heracles.

Python was the earth-dragon of Delphi, she always was represented in the vase-paintings and by sculptors as a serpent. Pytho was the chthonic enemy of Apollo, who slew her and remade her former home his own oracle, the most famous in Classical Greece.

Medusa and the other Gorgons were vicious female monsters with sharp fangs and hair of living, venomous snakes whose origins predate the written myths of Greece and who were the protectors of the most ancient ritual secrets. The Gorgons wore a belt of two intertwined serpents in the same configuration of the caduceus. The Gorgon was placed at the highest point and central of the relief on the Parthenon.

Asclepius, the son of Apollo and Koronis, learned the secrets of keeping death at bay after observing one serpent bringing another (which Asclepius himself had fatally wounded) healing herbs. To prevent the entire human race from becoming immortal under Asclepius's care, Zeus killed him with a bolt of lightning. Asclepius' death at the hands of Zeus illustrates man's inability to challenge the natural order that separates mortal men from the gods. In honor of Asclepius, snakes were often used in healing rituals. Non-poisonous snakes were left to crawl on the floor in dormitories where the sick and injured slept. The Bibliotheca claimed that Athena gave Asclepius a vial of blood from the Gorgons. Gorgon blood had magical properties: if taken from the left side of the Gorgon, it was a fatal poison; from the right side, the blood was capable of bringing the dead back to life. However, Euripides wrote in his tragedy Ion that the Athenian queen Creusa had inherited this vial from her ancestor Erichthonios, who was a snake himself and had received the vial from Athena. In this version the blood of Medusa had the healing power while the lethal poison originated from Medusa's serpents.

Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great and a princess of the primitive land of Epirus, had the reputation of a snake-handler, and it was in serpent form that Zeus was said to have fathered Alexander upon her. Alexander the false prophet[17] Aeetes, the king of Colchis and father of the sorceress Medea, possessed the Golden Fleece. He guarded it with a massive serpent that never slept. Medea, who had fallen in love with Jason of the Argonauts, enchanted it to sleep so Jason could seize the Fleece. (See Lamia (mythology)).

Nordic mythology 편집

Jörmungandr, alternately referred to as the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent, is a sea serpent of the Norse mythology, the middle child of Loki and the giantess Angrboða.

According to the Prose Edda, Odin took Loki's three children, Fenrisúlfr, Hel and Jörmungandr. He tossed Jörmungandr into the great ocean that encircles Midgard. The serpent grew so big that he was able to surround the Earth and grasp his own tail, and as a result he earned the alternate name of the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent. Jörmungandr's arch enemy is the god Thor.

African mythology 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

In Africa the chief centre of serpent worship was Dahomey, but the cult of the python seems to have been of exotic origin, dating back to the first quarter of the 17th century. By the conquest of Whydah the Dahomeyans were brought in contact with a people of serpent worshipers, and ended by adopting from them the beliefs which they at first despised. At Whydah, the chief centre, there is a serpent temple, tenanted by some fifty snakes. Every python of the danh-gbi kind must be treated with respect, and death is the penalty for killing one, even by accident. Danh-gbi has numerous wives, who until 1857 took part in a public procession from which the profane crowd was excluded; a python was carried round the town in a hammock, perhaps as a ceremony for the expulsion of evils. The rainbow-god of the Ashanti was also conceived to have the form of a snake. His messenger was said to be a small variety of boa, but only certain individuals, not the whole species, were sacred. In many parts of Africa the serpent is looked upon as the incarnation of deceased relatives. Among the Amazulu, as among the Betsileo of Madagascar, certain species are assigned as the abode of certain classes. The Maasai, on the other hand, regard each species as the habitat of a particular family of the tribe.

Native American mythology 편집

| This section does not cite any references or sources.(July 2013) |

In America some of the Native American tribes give reverence to the rattlesnake as grandfather and king of snakes who is able to give fair winds or cause tempest. Among the Hopi of Arizona the serpent figures largely in one of the dances. The rattlesnake was worshiped in the Natchez temple of the sun and the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl was a feathered serpent-god. In many Meso-American cultures, the serpent was regarded as a portal between two worlds. The tribes of Peru are said to have adored great snakes in the pre-Inca days and in Chile the Mapuche made a serpent figure in their deluge beliefs.

A Horned Serpent is a popular image in Northern American natives' mythology.

In one Native North American story, an evil serpent kills one of the gods' cousins, so the god kills the serpent in revenge, but the dying serpent unleashes a great flood. People first flee to the mountains and then, when the mountains are covered, they float on a raft until the flood subsides. The evil spirits that the serpent god controlled then hide out of fear.[20] The Mound Builders associated great mystical value to the serpent, as the Serpent Mound demonstrates, though we are unable to unravel the particular associations.

Snake worship in the Ancient Near East 편집

Snake cults were well established in Canaanite religion in the Bronze Age, for archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo,[21] one at Gezer,[22] one in the sanctum sanctorum of the Area H temple at Hazor,[23] and two at Shechem.[24]

In the surrounding region, serpent cult objects figured in other cultures. A late Bronze Age Hittite shrine in northern Syria contained a bronze statue of a god holding a serpent in one hand and a staff in the other.[25] In 6th-century Babylon, a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila.[26] At the Babylonian New Year's festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker and a goldsmith two images one of which "shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu".[27] At the tell of Tepe Gawra, at least seventeen Early Bronze Age Assyrian bronze serpents were recovered.[28]

Serpents in Judeo-Christian Mythology 편집

In the Hebrew Bible the serpent in the Garden of Eden lured Eve with the promise of forbidden knowledge, convincing her that despite God's warning, death would not be the result. The serpent is identified with wisdom: "Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made" (Genesis 3:1). There is no indication in Genesis that the Serpent was a deity in its own right, although it is one of only two cases of animals that talk in the Pentateuch, Balaam's ass being the other. Although the identity of the Serpent as Satan is implied in the Christian Book of Revelation,[29] in Genesis the Serpent is merely portrayed as a deceptive creature or trickster, promoting as good what God had directly forbidden, and particularly cunning in its deception. (Gen. 3:4–5 and 3:22)

The staff of Moses transformed into a snake and then back into a staff (Exodus 4:2–4). The Book of Numbers 21:6–9 provides an origin for an archaic copper serpent, Nehushtan by associating it with Moses. This copper snake according to the Biblical text is wrapped around a pole and used for healing. Book of Numbers 21:9 "And Moses made a snake of copper, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a snake had bitten any man, when he beheld the snake of brass, he lived."

When the reformer King Hezekiah came to the throne of Judah in the late 8th century BCE, "He removed the high places, broke the sacred pillars, smashed the idols, and broke into pieces the copper snake that Moses had made: for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it: and he called it Nehushtan."2 Kings 18:4.

In the Gospel of John 3:14–15, Jesus makes direct comparison between the raising up of the Son of Man and the act of Moses in raising up the serpent as a sign, using it as a symbol associated with salvation: "As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have eternal life".

Serpents in modern symbolism 편집

Modern medicine 편집

Snakes entwined the staffs both of Hermes (the caduceus) and of Asclepius, where a single snake entwined the rough staff. On Hermes' caduceus, the snakes were not merely duplicated for symmetry, they were paired opposites. (This motif is congruent with the phurba.) The wings at the head of the staff identified it as belonging to the winged messenger, Hermes, the Roman Mercury, who was the god of magic, diplomacy and rhetoric, of inventions and discoveries, the protector both of merchants and that allied occupation, to the mythographers' view, of thieves. It is however Hermes' role as psychopomp, the escort of newly-deceased souls to the afterlife, that explains the origin of the snakes in the caduceus since this was also the role of the Sumerian entwined serpent god Ningizzida, with whom Hermes has sometimes been equated.

In Late Antiquity, as the arcane study of alchemy developed, Mercury was understood to be the protector of those arts too and of arcane or occult "Hermetic' information in general. Chemistry and medicines linked the rod of Hermes with the staff of the healer Asclepius, which was wound with a serpent; it was conflated with Mercury's rod, and the modern medical symbol— which should simply be the rod of Asclepius— often became Mercury's wand of commerce. Another version is used in alchemy whereas the snake is crucified, known as Nicolas Flamel's caduceus. Art historian Walter J. Friedlander, in The Golden Wand of Medicine: A History of the Caduceus Symbol in Medicine (1992) collected hundreds of examples of the caduceus and the rod of Asclepius and found that professional associations were just somewhat more likely to use the staff of Asclepius, while commercial organizations in the medical field were more likely to use the caduceus.

Modern political propaganda 편집

Following the Christian context as a symbol for evil, serpents are sometimes featured in political propaganda. They were used to represent Jews in antisemitic propaganda. Snakes were also used to represent the evil side of drugs in such films as Narcotic[30] and Narcotics: Pit of Despair.[31]

See also 편집

- Dragon

- Dragons in Greek mythology

- Druids' glass

- Ethnoherpetology

- Genius loci

- Glycon

- Legend of the White Snake

- Nehushtan

- Reptilian humanoid

- Nahash

- Snakes in mythology

- Snakes in Chinese mythology

- Snake (zodiac)

- Snake worship

References 편집

- Burston, Daniel: 1994, "Freud, the Serpent & The Sexual Enlightenment of Children", International Forum of Psychoanalysis, vol. 3, pp. 205–219

- Joseph Campbell, Occidental Mythology: the Masks of God, 1964: Ch. 1, "The Serpent's Bride."

- John Bathurst Deane, The Worship of the Serpent, London : J. G. & F. Rivington, 1833. (alternative copy online at the Internet Archive)

- David P. Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 1992.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, 1896.

- Joseph Eddy Fontenrose, Python; a study of Delphic myth and its origins, 1959.

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, 1912. cf. Chapter IX, p. 329 especially, on the slaying of the Python.[32][33]

- Joseph Lewis Henderson and Maud Oakes, The Wisdom of the Serpent. The tribal initiation of the shaman, the archetype of the serpent, exemplifies the death of the self and a transcendent rebirth. Analytical psychology offers insights on the meaning of death symbolism and the serpent symbol.

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Cask of Amontillado, available in an online version at literature.org.

- Carl A. P. Ruck, Blaise Daniel Staples & Clark Heinrich, The Apples of Apollo: Pagan and Christian Mysteries of the Eucharist, 2001.

Notes 편집

- ↑ “Apollon, Python”. Apollon.uio.no. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《The Spiritual Technology of Ancient Egypt p223》. Books.google.com. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Savior, Satan, and Serpent: The Duality of a Symbol in the Scriptures”. Mimobile.byu.edu. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Monsen, Frederick. 《Festivals of the Hopi, and dancing and expression in all their national ceremonies》 (PDF).

- ↑ Hilda Roderick, Ellis Davidson (1988). 《Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions》. U.K.: Manchester University Press.

- ↑ “Myths Encyclopedia Serpents and Snakes”. Mythencyclopedia.com. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ 《The American journal of urology and sexology p 72》. 1984년 1월 1일. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Barton, SO "Midrash Rabba to Genesis", sec 20, p.93

- ↑ Her Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi Srivastava: "Meta Modern Era", pages 233-248. Vishwa Nirmala Dharma; first edition, 1995. ISBN 978-81-86650-05-9

- ↑ 《Vergil Aeneid 2.471》.

- ↑ 《Nicander Alexipharmaca 521》.

- ↑ 《Pliny Natural History 9.5》.

- ↑ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.13.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1971) [1968]. Walter F. Vella, 편집. 《The Indianized states of Southeast Asia》. translated by Susan Brown Cowing. Honolulu: Research Publications and Translations Program of the Institute of Advanced Projects, East-West Center, University of Hawaii. 48쪽. ISBN 0-7081-0140-2.

- ↑ Tossa, Wajuppa and Phra 'Ariyānuwat. 《Tossa, Wajuppa and Phra 'Ariyānuwat》. Cranbury, NJ: Bucknell University Press London. ISBN 0-8387-5306-X.

- ↑ Segal, Charles M. (1998). 《Aglaia: the poetry of Alcman, Sappho, Pindar, Bacchylides, and Corinna》. Rowman & Littlefield. 91쪽. ISBN 0-8476-8617-5. 필요 이상의 변수가 사용됨:

|author=및|last=(도움말) - ↑ “Lucian of Samosata : Alexander the False Prophet”. Tertullian.org. 2001년 8월 31일. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Jell-Bahlsen 1997, p. 105

- ↑ Chesi 1997, p. 255

- ↑ “Great Serpent and the Great Flood”. Indians.org. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ Gordon Loud, Megiddo II: Plates plate 240: 1, 4, from Stratum X (dated by Loud 1650–1550 BCE) and Statum VIIB (dated 1250–1150 BCE), noted by Karen Randolph Joines, "The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult" Journal of Biblical Literature 87.3 (September 1968:245-256) p. 245 note 2.

- ↑ R.A.S. Macalister, Gezer II, p. 399, fig. 488, noted by Joiner 1968:245 note 3, from the high place area, dated Late Bronze Age.

- ↑ Yigael Yadin et al. Hazor III-IV: Plates, pl. 339, 5, 6, dated Late Bronze Age II (Yadiin to Joiner, in Joiner 1968:245 note 4).

- ↑ Callaway and Toombs to Joiner (Joiner 1968:246 note 5).

- ↑ Maurice Viera, Hittite Art (London, 1955) fig. 114.

- ↑ Leonard W. King, A History of Babylon, p. 72.

- ↑ Pritchard ANET, 331, noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 8.

- ↑ E.A. Speiser, Excavations at Tepe Gawra: I. Levels I-VIII, p. 114ff., noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 9.

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0121587/

- ↑ “Narcotics: Pit of Despair (Part I) : Marshall (Mel) : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive”. Archive.org. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ “Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, Page 424”. Lib.uchicago.edu. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

- ↑ “EOS”. Lib.uchicago.edu. 2012년 12월 7일에 확인함.

External links 편집

- The caduceus vs the staff of Asclepius

- Dr Robert T. Mason, "The Divine serpent in myth and legend," 1999

- Links to further serpent myth

- Nagas and Serpents

- Snakes of the bible and the koran

- Jesus Our Serpent

- Scientific American – Offerings to a Stone Snake Provide the Earliest Evidence of Religion by J. R. Minkel 01/12/06

- Ophiolatreia – The Rites and mysteries connected with the origin, rise, and development of serpent worship in various parts of the world (1889)

- Depictions of Nagas (serpents) at Angkor in Cambodia

- Anthropology.net Rotherwas Ribbon – A Bronze Age Site ‘Unique In Europe’ 04/07/07

- Discovery News – Snake Cults Dominated Early Arabia 17/05/07

- The Genesis Factor, Stephan A. Hoeller, PhD 1997.

- Freud, the Serpent and the Sexual Enlightenment of Children by Daniel Burston

- Venus and a cosmic serpent among the Baruyas of Papua-New Guinea

Category:Dragons

Category:Greek legendary creatures

Category:Legendary serpents

Category:Matriarchy

Category:Symbols

Serpent (Bible) 편집

The serpent (נחש, nachash) occurs in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. The symbol of a serpent or snake played important roles in religious and cultural life of ancient Egypt, Canaan, Mesopotamia, and Greece. The serpent was a symbol of evil power and chaos from the underworld as well as a symbol of fertility, life, and healing.[2] Nachash, Hebrew for "snake", is also associated with divination, including the verb-form meaning to practice divination or fortune-telling. In the Hebrew Bible, Nachash occurs in the Torah to identify the serpent in Eden. Throughout the Hebrew Bible, it is also used in conjunction with saraph to describe vicious serpents in the wilderness. Tanniyn, a form of dragon-monster, also occurs throughout the Hebrew Bible. As in the Exodus, the staffs of Moses and Aaron are turned into serpents, a nachash for Moses, a tanniyn for Aaron. In the New Testament, the Book of Revelation makes use of Serpent several times to identify Satan, the Dragon an ancient Serpent (Rev.12:9; 20:2).

Hebrew Bible 편집

In the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Genesis refers to a serpent who was responsible for the Fall of Man (Gen 3:1-20). Serpent is also used to describe sea monsters. Examples of these identifications are in the Book of Isaiah where a reference is made to a serpent-like Leviathan (Isaiah 27:1), and in the Book of Amos where a serpent resides at the bottom of the sea (Amos 9:3). Serpent figuratively describes biblical places such as Egypt (Jer.46:22), and the city of Dan (Gen.49:17). The prophet Jeremiah also compares the King of Babylon to a serpent (Jer.51:34).

Serpent in Eden 편집

In the Book of Genesis, the Serpent is portrayed as a deceptive creature or trickster, who promotes as good what God had forbidden, and shows particular cunning in its deception. (cf. Gen. 3:4–5 and 3:22) The serpent appears in the Garden of Eden who tempts Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and denies that death will be a result. The Serpent has the ability to speak and to reason: "Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made" (Genesis 3:1). There is no indication in the Book of Genesis that the Serpent was a deity in its own right, although it is one of only two cases of animals that talk in the Pentateuch (Balaam's donkey being the other).

The Hebrew word nahash is used to identify the creature that appears in Genesis 3, in the Garden of Eden. God placed Adam in the Garden to tend it (Genesis 2:15), but he has warned Adam <Genesis 2:16> not to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, "or you will die". (Genesis 3:3, NIV) The serpent tells Eve that this is untrue, and that if she and the man eat the fruit they will have knowledge and will not die. So Adam and Eve eat the fruit, but the knowledge they gain is loss of childlike innocence, and they are banished from the Garden. The Snake is punished for its role in their fall by being made to crawl on its belly in the dust, from where it continues to bite the heel of man. According to the Rabbinical tradition, the serpent represents sexual desire.[1][3]

The serpent of Genesis plays the role of trickster, a speaking animal which even shares knowledge with God which is hidden from man. As with other trickster-figures, the gift it brings is double-edged: Adam and Eve gain knowledge, but lose Eden. The choice of a venomous snake for this role seems to arise from Near Eastern traditions associating snakes with danger and death, magic and secret knowledge, rejuvenation, immortality, and sexuality. It is also possible that the association of the snake with the nude goddess in Canaanite iconography lies behind the scene in the Garden between the reptile and naked Eve, "Mother of all life",[4] the "Great Mother Goddess of the Canaanites"[5] Qetesh.

Debate about the Serpent in Eden is whether it should be viewed figuratively or as a literal animal. Voltaire, drawing on Socinian influences, wrote: "It was so decidedly a real serpent, that all its species, which had before walked on their feet, were condemned to crawl on their bellies. No serpent, no animal of any kind, is called Satan, or Belzebub, or Devil, in the Pentateuch."[6]

20th Century scholars such as W. O. E. Oesterley (1921) were cognisant of the differences between the role of the Edenic serpent in the Hebrew Bible and any connection with "ancient serpent" in the New Testament.[7] Modern historiographers of Satan such as Henry Ansgar Kelly (2006) and Wray and Mobley (2007) speak of the "evolution of Satan",[8] or "development of Satan".[9]

Fiery serpents 편집

Fiery serpent m.n. (히브리어: 'שָׂרָף, 현대 히브리어: saraph, 티베리아 히브리어: sä·räf', "fiery", "fiery serpent", "seraph", "seraphim") occurs in the Torah, or Pentateuch, to describe a species of vicious snakes whose poison burns upon contact. According to Wilhelm Gesenius, saraph corresponds to the Sanskrit sarpa, serpent; sarpin, reptile (from the root srip, serpere).[10] These "burning serpents"(YLT) infested the great and terrible place of the desert wilderness (Num.21:4-9; Deut.8:15). The Hebrew word for "poisonous" literally means "fiery", "flaming" or "burning", as the burning sensation of a snake bite on human skin, a metaphor for the fiery anger of God (Numbers 11:1).[11]

The Book of Isaiah expounds on the description of these fiery serpents as "flying saraphs"(YLT), or flying dragons,[10] in the land of trouble and anguish (Isaiah 30:6). Isaiah indicates that these saraphs are comparable to vipers,(YLT) worse than ordinary serpents (Isaiah 14:29).[12] The prophet Isaiah also sees a vision of seraphim, in the Temple itself: but these are divine agents, with wings and human faces, and are probably not to be interpreted as serpent-like so much as flame-like.[4]

Serpent of bronze 편집

In the Book of Numbers, while Moses was in the wilderness, he mounted a serpent of bronze on a pole that functioned as a cure against the bite of the "seraphim", the "burning ones" (Numbers 21:4-9). The phrase in Num.21:9, "a serpent of bronze," is a wordplay as "serpent" (nehash) and “bronze” (nehoshet) are closely related in Hebrew, nehash nehoshet.[2]

Mainstream scholars suggest that the image of the fiery serpent served to function like that of a magical amulet. Magic amulets or charms were used in the ancient Near East[13] to practice a healing ritual known as sympathetic magic in an attempt to ward off, heal or reduce the impact of illness and poisons.[2] Copper and bronze serpent figures have been recovered, showing that the practice was widespread.[13] A Christian interpretation would be that the bronze serpent served as a symbol for each individual Israelite to take their confession of sin and the need for God’s deliverance to heart. Confession of sin and forgiveness was both a community and an individual responsibility. The plague of serpents remained an ongoing threat to the community and the raised bronze serpent was an ongoing reminder to each individual for the need to turn to the healing power of God.[2] It has also been proposed that the bronze serpent was a type of intermediary between God and the people[13] that served as a test of obedience, in the form of free judgment,[14] standing between the dead who were not willing to look to God’s chosen instrument of healing, and the living who were willing and were healed.[15] Thus, this instrument bore witness to the sovereign power of Yahweh even over the dangerous and sinister character of the desert.[14]

In 2 Kings 18:4, a bronze serpent, alleged to be the one Moses made, was kept in Jerusalem's Temple[2] sanctuary.[12] The Israelites began to worship the object as an idol or image of God, by offering sacrifices and burning incense to it, until Hezekiah was made King. Hezekiah referred to it as Nehushtan[16] and had tore it down. Scholars have debated the nature of the relationship between the Mosaic bronze serpent and Hezekiah’s Nehushtan, but traditions happen to link the two.[2]

New Testament 편집

Serpent in the Gospels 편집

In the Gospel of Matthew, John the Baptist calls the Pharisees and Saducees, who were visiting him, a "brood of vipers" (Matthew 3:7). Jesus also uses this imagery, observing: "Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of Gehenna?" (Matthew 23:33). Alternatively, Jesus also presents the snake with a less negative connotation when sending out the Twelve Apostles. Jesus exhorted them, "Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves" (Matthew 10:16). Wilhelm Gesenius notes that even amongst the ancient Hebrews, the serpent was a symbol of wisdom.[17]

In the Gospel of John, Jesus made mention of the Mosaic serpent when he foretold his crucifixion to a Jewish teacher.[15] Jesus compared the act of raising up the Mosaic serpent on a pole, with the raising up of the Son of Man on a cross (John 3:14–15).[18] Main: Nehushtan#Significance in Christianity

Temptation of the Christ 편집

In the temptation of Christ, the Devil cites Psalm 91:11–12 with, "for it is written, He shall give his angels charge concerning thee: and in [their] hands they shall bear thee up, lest at any time thou dash thy foot against a stone." (Matthew 4:6) Then he cuts off before the prophetic verse 13 of Psalms 91, "Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon (tanniyn)[20] shalt thou trample under feet." (Psalm 91:13 KJV)[21]

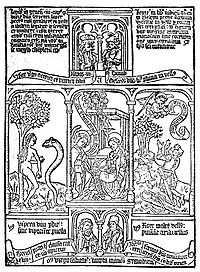

The Serpent m.n. (히브리어: תַּנִּין, 현대 히브리어: tanniyn, 티베리아 히브리어: tan·nēn', "dragon", "serpent", "whale", "sea monster") in Psalm 91:13 is identified as Satan by Christians:[22] "super aspidem et basiliscum calcabis conculcabis leonem et draconem" in the Latin Vulgate, literally "The asp and the basilisk you will trample under foot; you will tread on the lion and the dragon". This passage is commonly interpreted by Christians, as a reference to Christ defeating and triumphing over Satan. The passage led to the Late Antique and Early Medieval iconography of Christ treading on the beasts, in which two beasts are often shown, usually the lion and snake or dragon, and sometimes four, which are normally the lion, dragon, asp (snake) and basilisk (which was depicted with varying characteristics) of the Vulgate. All represented the devil, as explained by Cassiodorus and Bede in their commentaries on Psalm 91.[23] The serpent is often shown curled round the foot of the cross in depictions of the Crucifixion of Jesus from Carolingian art until about the 13th century; often it is shown as dead. The Crucifixion was regarded as the fulfillment of God's curse on the Serpent in Genesis 3:15. Sometimes it is pierced by the cross and in one ivory is biting Christ's heel, as in the curse.[24]

Ancient serpent 편집

Serpent m.n. (Greek: ὄφις;[25] Trans: Ophis, /o'-fēs/; "snake", "serpent") occurs in the Book of Revelation as the ancient serpent[26] or old serpent(YLT) used to describe the dragon,[20:2] Satan[27] the Adversary,(YLT) who is the Devil.[12:9, 20:2] This serpent is depicted as a red seven-headed dragon having ten horns, each housed with a diadem. The serpent battles Michael the Archangel in a War in Heaven which results in this devil being cast out to the earth. While on earth, he pursues the Woman of the Apocalypse. Unable to obtain her, he wages war with the rest of her seed (Revelation 12:1-18). He who has the key to the abyss and a great chain over his hand, binds the serpent for a thousand years. The serpent is then cast into the abyss and sealed within until he is released (Revelation 20:1-3).

In Christian tradition, the "ancient serpent" is commonly identified with the Genesis' Serpent and as Satan. This identification redefined the Hebrew Bible's concept of Satan ("the Adversary", a member of the Heavenly Court acting on behalf of God to test Job's faith), so that Satan/Serpent became a part of a divine plan stretching from Creation to Christ and the Second Coming.[28]

Serpents in biblical mythology 편집

In the oldest story ever written, the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh loses the power of immortality, stolen by a snake.[29] The serpent was a widespread figure in the mythology of the Ancient Near East. Ouroboros is an ancient symbol of a serpent eating its own tail that represents the perpetual cyclic renewal of life,[30] the eternal return, and the cycle of life, death and rebirth, leading to immortality.

Archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo,[31] one at Gezer,[32] one in the sanctum sanctorum of the Area H temple at Hazor,[33] and two at Shechem.[34] In the surrounding region, a late Bronze Age Hittite shrine in northern Syria contained a bronze statue of a god holding a serpent in one hand and a staff in the other.[35] In sixth-century Babylon, a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila.[36] At the Babylonian New Year festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker and a goldsmith two images one of which "shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu".[37] At the tell of Tepe Gawra, at least seventeen Early Bronze Age Assyrian bronze serpents were recovered.[38] The Sumerian fertility god Ningizzida was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head, eventually becoming a god of healing and magic.

Religious views of the Serpent in the post-Biblical period 편집

Jewish views 편집

The first Jewish source to connect the serpent with the devil may be Wisdom of Solomon.[39] The subject is more developed in Apocalypse of Moses (Vita Adae et Evae) where the devil works with the serpent.[40]

Christian views 편집

In traditional Christianity, a connection between the Serpent and Satan is strongly made, and Genesis 3:14-15 where God curses the serpent, is seen in that light: "And the LORD God said unto the serpent, Because thou hast done this, thou art cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life / And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel" (KJV).

Following the imagery of chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation, Bernard of Clairvaux had called Mary the "conqueror of dragons", and she was long to be shown crushing a snake underfoot, also a reference to her title as the "New Eve".[41]

A limited modern Christian association of religion with snakes is the snake handling ritual practiced in a small number of churches in the U.S., usually characterized as rural and Pentecostal. Practitioners quote the Bible to support the practice, especially the closing verses of the Gospel according to Mark:

- "And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." (Mark 16:17–18)

See also 편집

- Snakes in mythology

- Serpent (symbolism)

- Ethnoherpetology

- Staff of Moses

- Staff of Aaron

- Staff of Asclepius

- Staff of Mercury & Staff of Hermes (Caduceus)

- Caduceus as a symbol of medicine

- Nehushtan

- Satan;Devil;Lucifer

- Fall of Man

- Temptation

- Snake worship

- Church of God with Signs Following

- Ophites

- Naassenes

Footnotes 편집

- ↑ 가 나 The American journal of urology and sexology p 72

- ↑ 가 나 다 라 마 바 Olson 1996, 136쪽

- ↑ Barton, SO "Midrash Rabba to Genesis", sec 20, p.93

- ↑ 가 나 Toorn 1998, 746–7쪽

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Gorton 1824, 22쪽

- ↑ Oesterley Immortality and the Unseen World: a study in Old Testament religion (1921) "... moreover, not only an accuser, but one who tempts to evil. With the further development of Satan as the arch-fiend and head of the powers of darkness we are not concerned here, as this is outside the scope of the Old Testament."

- ↑ "The idea of Zoroastrian influence on the evolution of Satan is in limited favor among scholars today, not least because the satan figure is always subordinate to God in Hebrew and Christian representations, and Angra Mainyu ..."-Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2006). 《Satan : a biography》 1판. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 360쪽. ISBN 978-0-521-84339-3.

- ↑ Mobley, T.J. Wray, Gregory (2005). 《The birth of Satan : tracing the devil's biblical roots》. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6933-0.

- ↑ 가 나 Gesenius, Wilhelm & Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1893). 《Genenius's Hebrew and Chaldee lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures》. J. Wiley & Sons. dccxcv쪽.

- ↑ Olson 1996, 135쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Noth 1968, 156쪽

- ↑ 가 나 다 Thomas Nelson 2008, 172쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Noth 1968, 157쪽

- ↑ 가 나 Olson 1996, 137쪽

- ↑ Joines, Karen Randolph (1968). 《The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult》. JOBL, 87. 245, note 1쪽.

- ↑ Gesenius, Wilhelm & Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1893). 《Genenius's Hebrew and Chaldee lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures》. J. Wiley & Sons. dccxcvi쪽.

- ↑ C. H. Spurgeon, "The Mysteries of the Brazen Serpent", 1857

- ↑ The basilisk and the weasel by Wenceslas Hollar

- ↑ Strong's Concordance: H8577

- ↑ Whittaker, H.A. Studies in the Gospels "Matthew 4" Biblia, Cannock 1996

- ↑ Psalm 91 in the Hebrew/Protestant numbering, 90 in the Greek/Catholic liturgical sequence - see Psalms#Numbering

- ↑ Hilmo, Maidie. Medieval images, icons, and illustrated English literary texts: from Ruthwell Cross to the Ellesmere Chaucer, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004, p. 37, ISBN 0-7546-3178-8, ISBN 978-0-7546-3178-1, google books

- ↑ Schiller, I, pp. 112–113, and many figures listed there. See also Index.

- ↑ Strong's Concordance: G3789

- ↑ From the Greek: ἀρχαῖος, archaios (är-khī'-os) - Strong's Concordance Number G744

- ↑ Σατανᾶς, Satanas, (sä-tä-nä's) - of Aramaic origin corresponding to Σατάν (G4566) - Strong's Concordance Number G4567

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ↑ Storytelling, the Meaning of Life, and The Epic of Gilgamesh

- ↑ Mathematical Symbols and Scientific Icons

- ↑ Gordon Loud, Megiddo II: Plates plate 240: 1, 4, from Stratum X (dated by Loud 1650–1550 BC) and Statum VIIB (dated 1250-1150 BC), noted by Karen Randolph Joines, "The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult" Journal of Biblical Literature 87.3 (September 1968:245-256) p. 245 note 2.

- ↑ R.A.S. Macalister, Gezer II, p. 399, fig. 488, noted by Joiner 1968:245 note 3, from the high place area, dated Late Bronze Age.

- ↑ Yigael Yadin et al. Hazor III-IV: Plates, pl. 339, 5, 6, dated Late Bronze Age II (Yadiin to Joiner, in Joiner 1968:245 note 4).

- ↑ Callaway and Toombs to Joiner (Joiner 1968:246 note 5).

- ↑ Maurice Viera, Hittite Art (London, 1955) fig. 114.

- ↑ Leonard W. King, A History of Babylon, p. 72.

- ↑ Pritchard ANET, 331, noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 8.

- ↑ E.A. Speiser, Excavations at Tepe Gawra: I. Levels I-VIII, p. 114ff., noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 9.

- ↑ Alfred von Rohr Sauer, Concordia Theological Monthly 43 (1972): "The Wisdom of Solomon deserves to be remembered for the fact that it is the first tradition to identify the serpent of Gen. 3 with the devil: 'Through the devil's envy death entered the world' (2:24)".

- ↑ The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Expansions of the "Old ... James H. Charlesworth - 1985 "He seeks to destroy men's souls (Vita 17:1) by disguising himself as an angel of light (Vita 9:1, 3; 12:1; ApMos 17:1) to put into men "his evil poison, which is his covetousness" (epithymia, ..."

- ↑ Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, p. 108 & fig. 280, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 853312702

References 편집

- Toorn, editors: Bob Becking, Pieter W. van der Horst, Karel van der (1998). 《Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible (DDD)》 2., extensively rev.판. Leiden: Brill. 746–7쪽. ISBN 978-90-04-11119-6.

- Gorton, John G (1824). A+philosophical+dictionary+1824&hl=en&ei=UharTsamDIOWiALVvrH6Cg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false 《A philosophical dictionary, from the French of M. De Voltaire》 Vol. 4판. London: C. H. Reynell. 22쪽. 필요 이상의 변수가 사용됨:

|author=및|last=(도움말) - Thomas Nelson (2008). 《The chronological study Bible : New King James version.》. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson. 172쪽. ISBN 978-0-7180-2068-2. 필요 이상의 변수가 사용됨:

|author=및|last=(도움말) - Noth, Martin (1968). 《Numbers: A Commentary》 Issue 613, Vol. 7판. Westminster John Knox Press. 155–8쪽. ISBN 978-0-664-22320-5.

- Olson, Dennis T. (1996). 《Numbers》. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 135–8쪽. ISBN 978-0-8042-3104-6.

Category:Adam and Eve

Category:Garden of Eden

Category:Deities in the Hebrew Bible

Category:Talking animals in mythology

Category:Christian mythology

Category:Christian terms

Category:Jewish mythology

Category:New Testament words and phrases

Category:Legendary serpents

Category:Seven in the Book of Revelation

Flying serpent 편집

Flying serpent may refer to:

- Fiery flying serpent, an entity mentioned in the Bible

- Flying serpent (asterism), an asterism in a Chinese constellation

- The Flying Serpent, a 1946 film directed by Sam Newfield

See also 편집

Fiery flying serpent 편집

The fiery flying serpent is a creature mentioned in the Book of Isaiah (30:6).

Isaiah 편집

- Isaiah 14:29: "Do not rejoice, all you of Philistia, because the rod that struck you is broken; for out of the serpent's roots will come a viper, and its offspring will be a fiery flying serpent."

- Isaiah 30:6: "The burden against the beasts of the South. Through a land of trouble and anguish, from which came the lioness and the lion, the viper and the fiery flying serpent, they will carry their riches on the backs of young donkeys, and their treasures on the humps of camels, to a people who shall not profit;"

References to "fiery serpents" lacking a mention of flight can be found in several places in the Hebrew Bible.

- Deuteronomy 8:15 "Who led thee through that great and terrible wilderness, wherein were fiery serpents, and scorpions, and drought, where there was no water; who brought thee forth water out of the rock of flint;"

- Numbers 21:6-8 "(6) And the LORD sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died. (7) Therefore the people came to Moses, and said, We have sinned, for we have spoken against the LORD, and against thee; pray unto the LORD, that he take away the serpents from us. And Moses prayed for the people. (8) And the LORD said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live." This symbol, the Nehushtan, is similar to the ancient Greek Rod of Asklepios (frequently confused with the caduceus) and is frequently cited as an instance of the same archetype.

Book of Mormon 편집

- The Book of Mormon: 1Nephi 17:41 "...he sent fiery flying serpents among them; and after they were bitten he prepared a way that they might be healed;"

Herodotus 편집

In the History of Herodotus, Book 2, Herodotus describes flying winged serpents.

References 편집

Category:Animals in religion

Category:Dragons

Category:Animals in mythology

Category:Legendary serpents

Fiery serpents 편집

| This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. 사용자:배우는사람/틀:No footnotes |

A Fiery Serpent (also known as a snake-Lubac, Letun, Letuchy, Litavets, Maniac, nalyot, ognyanny and prelestnik) is an evil entity common to Slavic mythology, which presents itself as an anthropomorphic snake demon.

Description 편집

The Fiery Serpent generally resembles a glowing, fiery rocket, a flaming broom, or a ball of blue fire. According to the mythology, it is an evil spirit that reveals itself at night. The serpent has been portrayed as a spirit that presents itself as the form of a lost love to widows or women grieving the loss of a lover. In their grief, and their desperation to be rejoined with their lost love, women do not recognize the serpent and become convinced that their lover has returned.

The fiery serpent lacks the ability to hear and speak properly. It is told that those who are visited by the serpent experience weight loss, exhibit signs of insanity and eventually commit suicide.

Myths about the fiery serpent 편집

According to Eastern Ukrainian legends, whilst traveling, the fiery serpent throws beautiful gifts to grieving women and villagers, including beads, rings and handkerchiefs.

The serpent is often represented in Slavic folk tales as entering a person's house through the chimney. The serpent may bring gifts of gold - but those gifts turn to horse manure at sunrise. In addition, victims of the serpent often experience hallucinations, including visions of supernatural torment, such as suckling on breasts which excrete blood rather than milk. The fiery serpent has no spinal cord and cannot correctly pronounce certain words. For example, instead of "Jesus Christ," the serpent may say "Sus Christ", or "Chudoroditsa," in place of "Bogoroditsa" (mother of God), the woman who gave birth to a miracle.

If a child is born out of a relationship with the serpent, then that child is believed to be born with black skin, with hooves instead of feet, eyes without eyelids and a cold body. Such a child is fated to live a very short life.

Sources of information 편집

Myths about the fiery serpent are found in Serbian epic songs in Russian bylinas, fairy tales and conspiracies, as well as the hagiographic Story of Peter and Fevronia of Murom, which is based on folk material.

The origin of the image 편집

Visible manifestations of a fiery serpent show fireballs flying deviated or horizontal, which can be seen rushing through the air in the form of long, wide ribbons of red sparks. The image of a flying dragon was associated with signs of temporary insanity, depression, or hallucinations - particularly in women who have lost their loved ones.

Fiery serpents in the literature 편집

The image of a fiery serpent was described by the Russian poet Afanasy Afanasievich Fet in his ballad, "Snake", written in 1847.

References 편집

- М. Забылин «Русский народ, его обычаи, обряды, предания, суеверия и поэзия», — М: Амрита, 2011, С. 204—205. ISBN 978-5-413-00397-8

- Е. Е. Левкиевская «Мифы русского народа», — М: Астрель, 2011, С. 442—445. ISBN 978-5-271-24693-7

- «Славянская мифология. Энциклопедический словарь» (издание РАН), — М, Эллис Лак, 1995, С. 283—284. ISBN 5-7195-0057-X

Category:Slavic legendary creatures

Category:Russian mythology

Category:Magic (paranormal)