사용자:배우는사람/문서:Chapter I - The Gods Of Egypt (1-17)

Chapter I - The Gods Of Egypt 편집

[Page 1] The Greek historian Herodotus affirms1) that the Egyptians were “beyond measure scrupulous (세심한) in all matters appertaining to religion,” and he made this statement after personal observation of the care which they displayed in the performance of religious ceremonies, the aim and object of which was to do honour to the gods, and of the obedience which they showed to the behests (명령) of the priests who transmitted to them commands which they declared to be, and which were accepted as, authentic revelations of the will of the gods. From the manner in which this writer speaks it is clear that he had no doubt about what he was saying, and that he was recording a conviction which had become settled in his mind.

1) ii. 64.

He was fully conscious that the Egyptians worshipped a large number of animals, and birds, and reptiles, with a seriousness and earnestness which must have filled the cultured Greek with astonishment, yet he was not moved to give expression to words of scorn as was Juvenal,2) for Herodotus perceived that beneath the acts of apparently [Page 2] foolish and infatuated (심취한) worship there existed a sincerity which betokened (징조이다) a firm and implicit belief which merited (받을 만하다) the respect of thinking men.

2)

“Quis nescit, Volusi Bithynice, qualia demens

Aegyptus portenta colat ? crocodilon adorat

Pars haec, ilia pavet saturam serpentibus ibin.

Effigies sacri nitet aurea cercopitbeci,

Dimidio magicae resonant ubi Memnone chordae

Atque vetus Thebe centum jacet obruta portis.

Illic aeluros, hie piscem fluminis, illic

Oppida tota canem venerantur, nemo Dianam.

Porrum efc caepe nefas violare et frangere inorsu :

O sanctas gentes, quibus haec nascuntur in hortis

Numina ! Lanatis animalibus abstinet omnis

Mensa, nefas illic fetum ingulare capellae :

Carnibus humanis vesci licet.”

—Satire, xv. 1—13.

That the crocodile, ibis, dog-headed ape, and fish of various kinds were venerated in Egypt is true enough; they were not, however, venerated in dynastic times as animals, but as the abodes of gods. In certain localities peculiar sanctity was attributed to the leek (리크) and onion, as Juvenal suggests, but neither vegetable was an object of worship in the country generally; and there is no monumental (기념물에 나타난) evidence to show that the eating of human flesh was practised, for it is now known that even the predynastic Egyptians did not eat the flesh of the dead and gnaw (물어뜯다) their bones, as was once rashly (무분별하게) asserted. Juvenal’s statements are only partly true, and some of them are on a par with (같은) that of a learned Indian who visited England, and wrote a book on this country after his return to Bombay. Speaking of the religion of the English he declared that they were all idolators, and to prove this assertion he gave a list of churches in which he had seen a figure of a lamb in the sculpture work over and about the altar, and in prominent places elsewhere in the churches. The Indian, like Juvenal, and Cicero also, seems not to have understood that many nations have regarded animals as symbols of gods and divine powers, and still do so.

Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late 1st and early 2nd century AD, author of the Satires. The details of the author's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD fix his terminus post quem (earliest date of composition).

In accord with the manner of Lucilius—the originator of the genre of Roman satire—and within a poetic tradition that also included Horace and Persius, Juvenal wrote at least 16 poems in dactylic hexameter covering an encyclopedic range of topics across the Roman world. While the Satires are a vital source for the study of ancient Rome from a vast number of perspectives, their hyperbolic, comedic mode of expression makes the use of statements found within them as simple fact problematic. At first glance the Satires could be read as a critique of pagan Rome, perhaps ensuring their survival in Christian monastic scriptoria, a bottleneck in preservation when the large majority of ancient texts were lost.

데키무스 유니우스 유베날리스(라틴어: Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis 데키무스 유니우스 유웨날리스[*])는 1세기 후반에서 2세기 초반에 활동한 고대 로마의 시인이다. 도미티아누스 황제를 비롯해 수많은 황제들과 로마의 귀족들, 당시의 사회상에 대한 통렬하지만 유쾌한 풍자시로 유명하며 당시의 라틴 문학은 물론 후대의 풍자작가들에 많은 영향을 끼쳤다.

유베날리스의 생애에 대하여는 확실한 근거를 가진 사료가 별로 없다. 그에 관한 전기도 상당수는 유베날리스가 죽은 지 오랜 시간이 지난후에 쓰여진것으로 보인다. 단지 그의 풍자시에서 단편적으로 유베날리스의 삶을 유추할 수 있다.

유베날리스의 풍자시집은 모두 16편으로 알려져있고 다섯권의 책으로 나뉘어 있다.

- 제1권 : 풍자시 1-5 편

- 제2권 : 풍자시 6편

- 제3권 : 풍자시 7-9편

- 제4권 : 풍자시 10-12편

- 제5권 : 풍자시 13-16편 (풍자시 16편은 미완성인채로 남아있음)

Antiquity Of Religious Observances 편집

It would be wrong to imagine that the Egyptians were the only people of antiquity who were scrupulous beyond measure in religious matters, for we know that the Babylonians, both Sumerian and Semitic, were devoted worshippers of their gods, and that they possessed a very old and complicated system of religion; but there is good reason for thinking that the Egyptians were more scrupulous than their neighbours in religious matters, and that they always bore the character of being an extremely religious nation.

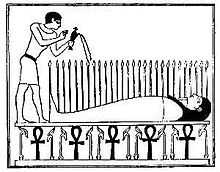

The evidence of the monuments of the Egyptians proves that from the earliest to the latest period of their history the observance of religious festivals and the performance of religious duties in connexion with the worship of the gods absorbed a very large part of the time and energies of the nation, and if we take into consideration the funeral ceremonies and services commemorative (기념하는) of the dead which were performed by them at the tombs, a casual visitor to Egypt who did not know how to look below the surface might be pardoned for (...에 대해 용서를 구하다) declaring that the [Page 3] Egyptians were a nation of men who were wholly given up to the worship of beasts and the cult of the dead.

Divine Origin Of Kings 편집

The Egyptians, however, acted in a perfectly logical manner, for they believed that they were a divine nation, and that they were ruled by kings who were themselves gods incarnate; their earliest kings, they asserted, were actually gods, who did not disdain (업신여기다) to live upon earth, and to go about and up and down through it, and to mingle with men. Other ancient nations were content to believe that they had been brought into being by the power of their gods operating upon matter, but the Egyptians believed that they were the issue of the great God who created the universe, and that they were of directly divine origin.

When the gods ceased to reign in their proper persons upon earth, they were succeeded by a series of demi-gods, who were in turn succeeded by the Manes, and these were duly (적절한 절차에 따라) followed by kings in whom was enshrined (소중히 간직하다) a divine nature with characteristic attributes. When the physical or natural body of a king died, the divine portion of his being, i.e., the spiritual body, returned to its original abode with the gods, and it was duly worshipped by men upon earth as a god and with the gods.

This happy result was partly brought about by the performance of certain ceremonies, which were at first wholly magical, but later partly magical and partly religious, and by the recital (낭송) of appropriate words uttered in the duly (적절한 절차에 따라) prescribed tone and manner, and by the keeping of festivals at the tombs at stated seasons when the appointed offerings were made, and the prayers for the welfare of the dead were said. From the earliest times the worship of the gods went hand in hand with the deification of dead kings and other royal personages, and the worship of departed monarchs from some aspects may be regarded as meritorious (칭찬할 만한) as the worship of the gods.

From one point of view Egypt was as much a land of gods as of men, and the inhabitants of the country wherein the gods lived and moved naturally devoted a considerable portion of their time upon earth to the worship of divine beings and of their ancestors who had departed to the land of the gods. In the matter of religion, and all that appertains thereto (그것에 관련된), the Egyptians were a “peculiar people,” and in all ages they have exhibited a tenacity (지속적인) of belief [Page 4] and a conservatism which distinguish them from all the other great nations of antiquity.

In ancient Roman religion, the Manes or Di Manes are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the Lares, Lemures, Genii, and Di Penates as deities (di) that pertained to domestic, local, and personal cult. They belonged broadly to the category of di inferi, "those who dwell below,"[1] the undifferentiated collective of divine dead.[2] The Manes were honored during the Parentalia and Feralia in February.

Number And Variety Of Gods 편집

But the Egyptians were not only renowned for their devotion to religious observances, they were famous as much for the variety as for the number of their gods. Animals, birds, fishes, and reptiles were worshipped by them in all ages, but in addition to these they adored the great powers of nature as well as a large number of beings with which they peopled the heavens, the air, the earth, the sky, the sun, the moon, the stars, and the water. In the earliest times the predynastic Egyptians, in common with (~와 마찬가지로) every half-savage people, believed that all the various operations of nature were the result of the actions of beings which were for the most part unfriendly to man.

홍수와 범람 편집

The inundation which rose too high and flooded the primitive village, and drowned their cattle, and destroyed their stock of grain, was regarded as the result of the working of an unfriendly and unseen power; and when the river rose just high enough to irrigate the land which had been prepared, they either thought that a friendly power, which was stronger than that which caused the destroying flood, had kept the hostile power in check (억제하다), or that the spirit of the river was on that occasion pleased with them.

정령 편집

They believed in the existence of spirits of the air, and in spirits of mountain, and stream, and tree, and all these had to be propitiated (달래다) with gifts, or cajoled (발라맞추다) and wheedled (구슬리다) into bestowing their favour and protection upon their suppliants (탄원자, 애원자).

God And "gods" And Angels 편집

neteru · neter 편집

It is very unfortunate that the animals, and the spirits of natural objects, as well as the powers of nature, were all grouped together by the Egyptians and were described by the word neteru, which, with considerable inexactness, we are obliged to translate by “gods.” There is no doubt that at a very early period in their predynastic history the Egyptians distinguished between great gods and little gods, just as they did between friendly gods and hostile gods, but either their poverty of expression, or the inflexibility of their language, prevented them from making a distinction apparent in writing, and thus it happens that in dynastic times, when a lofty conception of monotheism prevailed among the priesthood, the scribe found [Page 5] himself obliged to call both God and the lowest of the beings that were supposed to possess some attribute of divinity by one and the same name, i.e., neter.

Definition

| "Deity" in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

or

or

nṯr "god"[3] | ||||||||||

nṯr.t "goddess"[3] | ||||||||||

The beings in ancient Egyptian tradition who might be labeled as deities are difficult to count. Egyptian texts list the names of many deities whose nature is unknown and make vague, indirect references to other gods who are not even named.[4] The Egyptologist James P. Allen estimates that more than 1,400 deities are named in Egyptian texts,[5] whereas his colleague Christian Leitz says there are "thousands upon thousands" of gods.[6]

The Egyptian terms for these beings were nṯr, "god", and its feminine form nṯrt, "goddess".[7] Scholars have tried to discern the original nature of the gods by proposing etymologies for these words, but none of these suggestions has gained acceptance, and the terms' origin remains obscure. The hieroglyphs that were used as ideograms and determinatives in writing these words show some of the characteristics that the Egyptians connected with divinity.[8] The most common of these signs is a flag flying from a pole; similar objects were placed at the entrances of temples, representing the presence of a deity, throughout ancient Egyptian history. Other such hieroglyphs include a falcon, reminiscent of several early gods who were depicted as falcons, and a seated male or female deity.[9] The feminine form could also be written with an egg as determinative, connecting goddesses with creation and birth, or with a cobra, reflecting the use of the cobra to depict many female deities.[8]

The Egyptians distinguished nṯrw, "gods", from rmṯ, "people", but the meanings of the Egyptian and the English terms do not match perfectly. The term nṯr may have applied to any being that was in some way outside the sphere of everyday life.[10] Deceased humans were called nṯr because they were considered to be like the gods,[11] whereas the term was rarely applied to many of Egypt's lesser supernatural beings, which modern scholars often call "demons".[6] Egyptian religious art also depicts places, objects, and concepts in human form. These personified ideas range from deities that were important in myth and ritual to obscure beings, only mentioned once or twice, that may be little more than metaphors.[12]

Confronting these blurred distinctions between gods and other beings, scholars have proposed various definitions of a "deity". One widely accepted definition,[6] suggested by Jan Assmann, says that a deity has a cult, is involved in some aspect of the universe, and is described in mythology or other forms of written tradition.[13] According to a different definition, by Dimitri Meeks, nṯr applied to any being that was the focus of ritual. From this perspective, "gods" included the king, who was called a god after his coronation rites, and deceased souls, who entered the divine realm through funeral ceremonies. Likewise, the preeminence of the great gods was maintained by the ritual devotion that was performed for them across Egypt.[14]

Muḥammadan And Syrian Angels 편집

Other nations of antiquity found a way out of the difficulty of grouping all classes of divine beings by one name by inventing series of orders of angels, to each of which they gave names and assigned various duties in connexion with the service of the Deity.

코란의 천사 편집

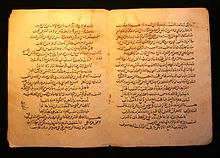

Thus in the Ḳurʻan (Sura xxxv.) it is said that God maketh the angels His messengers and that they are furnished with two, or three, or four pairs of wings, according to their rank and importance; the archangel Gabriel is said to have been seen by Muhammad the Prophet with six hundred pairs of wings!

Surah Initiator (Faater) Pickthall In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. |

Surah Initiator (Faater) Ahmed Ali In the name of Allah, most benevolent, ever-merciful. |

|

| Qur'an 35:1 | Praise be to Allah, the Creator of the heavens and the earth, Who appointeth the angels messengers having wings two, three and four. He multiplieth in creation what He will. Lo! Allah is Able to do all things. | ALL PRAISE BE to God, the originator of the heavens and the earth, who appointed angels as His messengers, with wings, two, three and four. He adds what He pleases to His creation. He has certainly power over everything. |

코란의 천사들의 의무 편집

The duties of the angels, according to the Muhammadans, were of various kinds.

- Thus nineteen angels are appointed to take charge of hell fire (Sura lxxiv.);

- eight are set apart to support God’s throne on the Day of Judgment (Sura lxix.);

- several tear the souls of the wicked from their bodies with violence, and several take the souls of the righteous from their bodies with gentleness and kindness (Sura lxxix.);

- two angels are ordered to accompany every man on earth, the one to write down his good actions and the other his evil deeds, and these will appear with him at the Day of Judgment, the one to lead him before the Judge, and the other to bear witness either for or against him (Sura 1.).

이슬람교의 천사 편집

Muhammadan theologians declare that

- the angels are created of a simple substance of light, and that

- they are endowed with life, and speech, and reason;

- they are incapable of sin,

- they have no carnal desire,

- they do not propagate their species, and

- they are not moved by the passions of wrath and anger;

- their obedience is absolute.

- Their meat is the celebrating of the glory of God,

- their drink is the proclaiming of His holiness,

- their conversation is the commemorating (기념하다) of God, and

- their pleasure is His worship.

Curiously enough, some are said to have the form of animals.

이슬람교의 4대천사 편집

Four of the angels are Archangels, viz.

- Michael,

- Gabriel,

- Azrael,

- and Israfel,

and they possess special powers, and special duties are assigned to them. These four are superior to all the human race, with the exception of the Prophets and Apostles, but the angelic nature is held to be inferior to human nature because all the angels were commanded to worship [Page 6] Adam (Sura ii.).

Angels (ملائكة malāʾikah; singular: ملاك malāk) are heavenly beings mentioned many times in the Quran and hadith. Unlike humans or jinn, they have no free will and therefore can do only what God orders them to do. An example of a task they carry out is testing individuals by granting them abundant wealth and curing their illness.[15] Believing in angels is one of the six Articles of Faith in Islam. Just as humans are made of clay, and jinn are made of smokeless fire, angels are made of light.[16]

Angel hierarchy

There is no standard hierarchical organization in Islam that parallels the division into different "choirs" or spheres, as hypothesized and drafted by early medieval Christian theologians. Most[누가?] Islamic scholars agree that this is an unimportant topic in Islam, simply because angels have a simple existence in obeying God already, especially since such a topic has never been directly addressed in the Quran. However, it is clear that there is a set order or hierarchy that exists between angels, defined by the assigned jobs and various tasks to which angels are commanded by God. Some scholars suggest that Islamic angels can be grouped into fourteen categories as follows, of which numbers two-five are considered archangels. Not all angels are known by Muslims however, the Quran and hadith only mentions a few by name. Due to varied methods of translation from Arabic and the fact that these angels also exist in Christian contexts and the Bible, several of their Christian and phonetic transliteral names are listed:

- Jibrail/Jibril (Judeo-Christian, Gabriel), the angel of revelation, who is said to be the greatest of the angels. Jibrail is the archangel responsible for revealing the Quran to Muhammad, verse by verse. Jibrail is widely known as the angel who communicates with (all of) the prophets and also for coming down with God's blessings during the night of Laylat al-Qadr ("The Night of Power").

Israfil or Israafiyl (Judeo-Christian, Raphael), is an archangel in Islam who will blow the trumpet twice at the end of time. According to the hadith, Israfil is the angel responsible for signaling the coming of Qiyamah (Judgment Day) by blowing a horn. The blowing of the trumpet is described in many places in the Quran. It is said that the first blow will bring all to attention. The second will end all life,[17] while the third blow will bring all human beings back to life again to meet their Lord for their final judgement.[18]

- Mikail (Judeo-Christian, Michael),[19] who provides nourishments for bodies and souls. Mikail is often depicted as the archangel of mercy who is responsible for bringing rain and thunder to Earth. He is also responsible for the rewards doled out to good people in this life.

- 'Azrael/'Azraaiyl also known as Malak al-maut (Judeo-Christian, Azrael), the angel of death. He is responsible for parting the soul from the body. He is only referred as malak al-maut, meaning angel of death, in the Quran.[20]

Azrael is the Archangel of Death in some traditions. He is also the angel of retribution in Islamic theology and Sikhism. The name Azrael is an English form of the Arabic name ʿIzrāʾīl (عزرائيل) or Azra'eil (عزرایل), the name traditionally attributed to the angel of death in some sects of Islam and Sikhism, as well as some Hebrew lore.[21][22] The Qur'an never uses this name, rather referring to Malak al-Maut (which translates directly as angel of death). Also spelt Izrail, Azrin, Izrael, Azriel, Azrail, Ezraeil, Azraille, Azryel, Ozryel, or Azraa-eel, the Chambers English dictionary uses the spelling Azrael. The name literally means Whom God Helps,[21] in an adapted form of Hebrew.

Background

Depending on the outlook and precepts of various religions in which he is a figure, Azrael may be portrayed as residing in the Third Heaven.[23] In one of his forms, he has four faces and four thousand wings, and his whole body consists of eyes and tongues, the number of which corresponds to the number of people inhabiting the Earth. He will be the last to die, recording and erasing constantly in a large book the names of men at birth and death, respectively.[24]

In Judaism

In Jewish mysticism, he is commonly referred to as "Azriel," not "Azrael." The Zohar (a holy book of the Jewish mystical tradition of Kabbalah), presents a positive depiction of Azriel. The Zohar says that Azriel receives the prayers of faithful people when they reach heaven, and also commands legions of heavenly angels. Accordingly, Azriel is associated with the South and is considered to be a high-ranking commander of God's angels. (Zohar 2:202b)

In Christianity

There is no reference to Azrael in the bible, and he is not considered a canonical character within Christianity. However, a story from Folk-lore of the Holy Land: Moslem, Christian and Jewish by J. E. Hanauer tells of a soldier with a gambling addiction avoiding Azrael. Because the soldier goes to Jesus and asks for help, then later must see Jesus and repent to be allowed back in Heaven, this is seen as a Christian account of Azrael. However, it does not specify whether Azrael is an angel of death, or an angel of punishment in this story.

In Islam

In some cultures and sects, Azrael (also pronounced as ʿIzrāʾīl /Azriel) is the name referring to the Angel of Death by some Arabic speakers. The name is mentioned in a few Muslim books but is argued by some Muslims as having no basis of reference.[출처 필요] Along with Jibrīl, Mīkhā'īl, Isrāfīl and other angels, the Angel of Death is believed by Muslims to be one of the archangels.[25] The Qur'an states that the angel of death takes the soul of every person and returns it to God.[26] However, the Qur'an makes it clear that only God knows when and where each person will be taken by death,[27] thus making it clear that the Angel of Death has no power of his own. Several Muslim traditions recount meetings between the Angel of Death and the prophets, the most famous being a conversation between the Angel of Death and Moses.[25] He watches over the dying, separates the soul from the body, and receives the spirits of the dead in Muslim belief. Rather than merely representing death personified, the Angel of Death is usually described in Islamic sources as subordinate to the will of God "with the most profound reverence."[28] However, there is no reference within the Qur'an or any Islamic teachings giving the angel of death the name of Azrael.

Some have also disputed the usage of the name Azrael as it's not used in the Qur'an itself.[출처 필요] However, the same can be said about many Prophets and Angels, many of whom aren't mentioned by name in the Qur'an.

Riffian (Berber) men of Morocco had the custom of shaving the head but leaving a single lock of hair on either the crown, left, or right side of the head, so that the angel Azrael is able "to pull them up to heaven on the Last Day."[29]

In Sikhism

In Sikh scriptures written byGuru Nanak Dev Ji, God (Waheguru) sends Azrael to people who are unfaithful and unrepentant for their sins. Azrael appears on Earth in human form and hits sinful people on the head with his scythe to kill them and extract their souls from their bodies. He then brings their souls to hell, and makes sure that they get the punishment that Waheguru decrees once he judges them. This would portray him as more of an avenging angel, or angel of retribution, rather than a simple angel of death. It is unknown which story of Azrael this view is taken from. [30]

Israfil ({{{2}}}, Alternate Spelling: Israfel , Meaning: The Burning One [31] ), is the angel of the trumpet in Islam,[32] though unnamed in the Qur'an. Along with Mikhail, Jibrail and Izra'il, he is one of the four Islamic archangels.[31] Israfil will blow the trumpet from a holy rock in Jerusalem to announce the Day of Resurrection.[33] The trumpet is constantly poised at his lips, ready to be blown when God so orders. In Judeo-Christian biblical literature, Raphael is the counterpart of Isrāfīl.[33] Isrāfīl is usually conceived as having a huge, hairy body that is covered with mouths and tongues and that reaches from the seventh heaven to the throne of God. One wing protects his body, another shields him from God, while the other two extend east and west. He is overcome by sorrow and tears three times every day and every night at the sight of Hell. It is said that Isrāfīl tutored Muhammad for three years in the duties of a prophet before he could receive the Qurʾān.[33]

In religious tradition

Although the name "Israfel" does not appear in the Quran, mention is repeatedly made of an unnamed trumpet-angel assumed to identify this figure:

- "And the trumpet shall be blown, so all those that are in the heavens and all those that are in the earth shall swoon, except Allah; then it shall be blown again, then they shall stand up awaiting." —Qur'an (39.68).

In Islamic tradition he is said to have been sent, along with the other three Islamic archangels, to collect dust from the four corners of the earth,[34] although only Izra'il succeeded in this mission.[35] It was from this dust that Adam was formed.틀:Verify credibility

Israfil has been associated with a number of other angelic names not pertaining to Islam, including Uriel,[36] Sarafiel[37] and Raphael.[38]

Certain sources indicate that, created at the beginning of time, Israfil possesses four wings, and is so tall as to be able to reach from the earth to the pillars of Heaven.[34] A beautiful angel who is a master of music, Israfil sings praises to God in a thousand different languages, the breath of which is used to inject life into hosts of angels who add to the songs themselves.[31]

According to Sunni traditions reported by Imam Al-Suyuti, the Ghawth or Qutb, who is regarded among Sufis as the highest person in the rank of siddiqun (saints), is someone who has a heart that resembles that of Archangel Israfil, signifying the loftiness of this angel. The next in rank are the saints who are known as the Umdah or Awtad, amongst whom the highest ones have their hearts resembling that of Angel Michael, and the rest of the lower ranking saints having the heart of Jibreel or Gabriel, and that of the previous prophets before the Prophet Muhammad. The earth is believed to always have one of the Qutb.[39]

In 19th-century Occultism

Israfil appears in cabbalistic lore as well as 19th-century Occultism. He was referenced in the title of Aleister Crowley's Liber Israfil, formerly Liber Anubis, a ritual which in its original form was written and utilized by members of the Golden Dawn. This is a ritual designed to invoke the Egyptian god, Thoth,[40] the deity of wisdom, writing, and magic who figures large in the Hermetica attributed to Hermes Trismegistus upon which modern practitioners of Alchemy and Ceremonial Magic draw.

In literature

- Israfil is the subject and title of a poem by Edgar Allan Poe, used for the exotic effect of the name:

- In Heaven a spirit doth dwell

- Whose heart-strings are a lute;

- None sing so wildly well

- As the angel Israfil,

- And the giddy stars (so legends tell),

- Ceasing their hymns, attend the spell

- Of his voice, all mute.

- Israfil appears as a character in the book Heavenly Discourse by C. E. S. Wood.

- Israfil is a character in the Remy Chandler book series - specifically the book A kiss before the Apocalypse - by Thomas E. Sniegoski. In that series he plays the part of the Angel of Death.

- Israfil appears as an angelic character in the Sheri S. Tepper book - "Beauty".

See also

- Angel

- Archangel

- Angels in Islam - an article on Angles in Islam

- Seraph

- Eschatology

- Resurrection

이슬람교의 천사와 이집트 하급신들의 유사성 편집

The above and many other characteristics might be cited in proof that the angels of the Muḥammadans possess much in common with the inferior gods of the Egyptians, and though many of the conceptions of the Arabs on this point were undoubtedly borrowed from the Hebrews and their writings, a great many must have descended to them from their own early ancestors.

시리아의 천사 체계: 3위 9등급 체계 편집

Closely connected with these Muḥammadan theories, though much older, is the system of angels which was invented by the Syrians. In this we find the angels divided into nine classes and three orders, upper, middle, and lower.

- The upper order is composed of

- Cherubim,

- Seraphim, and

- Thrones ;

- the middle order of

- Lords,

- Powers, and

- Rulers; and

- the lower order of

- Principalities,

- Archangels, and

- Angels.

The middle order receives revelations from those above them, and the lower order are the ministers who wait upon created things.

시리아의 천사 체계의 최고위 천사: 가브리엘 편집

The highest and foremost among the angels is Gabriel, who is the mediator between God and His creation. The Archangels in this system are described as a “swift operative motion,” which has dominion over every living thing except man; and the Angels are a motion which has spiritual knowledge of everything that is on earth and in heaven.3)

3) See my edition of the Book of the Bee, by Solomon of Al-Baṣra. Oxford, 1886, pp. 9-11.

시리아의 천사 체계의 기원과 이집트 하급신과의 유사성 편집

The Syrians, like the Muḥammadans, borrowed largely from the writings of the Hebrews, in whose theological system angels played a very prominent part. In the Syrian system also the angels possess much in common with the inferior gods of the Egyptians.

Hebrew Angels Or "gods" 편집

이집트 하급신의 성격 편집

The inferior gods of the Egyptians

- were supposed to suffer from many of the defects of mortal beings, and

- they were even thought to grow old and to die, and the same ideas about the angels were held by Muḥammadans and Hebrews.

이슬람의 천사의 성격 편집

According to the former (이슬람교), the angels will perish when heaven, their abode, is made to pass away at the Day of Judgment.

유대교의 천사의 성격 편집

According to the latter (유대교), one of the two great classes of angels, i.e., those which were created on the fifth day of creation, is mortal; on the other hand, the angels which were created on the second day of creation [Page 7] endure for ever, and these may be fitly compared with the unfailing and unvarying powers of nature which were personified and worshipped by the Egyptians; of the angels which perish, some spring from fire, some from water, and some from wind.

유대교의 천사의 하이어라키: 10등급 편집

The angels are grouped into ten classes, i.e.,

- the Erêlîm,

- the Îshîm,

- the Bĕnê Elôhîm,

- the Malachîm,

- the Ḥaslimalîm,

- the Tarshîshîm,

- the Shislianîm,

- the Cherûbîm,

- the Ophannîm,

- and the Serâphim;4)

among these were divided all the duties connected with the ordering (정리, 배치) of the heavens and the earth, and they, according to their position and importance, became the interpreters of the Will of the Deity.

4) See the chapter “Was die Judeu von den guten Engeln lehren” in Eisenmenger, Entdeckten Judenthums, vol. ii. p. 370 ff.

Angels in Judaism (angel: מַלְאָךְ mal’āḵ, plural mal’āḵīm) appear throughout the Hebrew Bible, Talmud, Rabbinic literature, and traditional Jewish liturgy. They are categorized in different hierarchies.

Maimonides

Maimonides, in his Mishneh Torah or Yad ha-Chazakah: Yesodei ha-Torah, counts ten ranks of angels in the Jewish angelic hierarchy, beginning from the highest:

| Rank | Angel | Notes |

| 1 | Chayot HaKodesh | See Ezekiel chs. 1 and 10 |

| 2 | Ophanim | See Ezekiel chs. 1 and 10 |

| 3 | Erelim | See Isaiah 33:7 |

| 4 | Hashmallim | See Ezekiel 1:4 |

| 5 | Seraphim | See Isaiah 6 |

| 6 | Malakim | Messengers, angels |

| 7 | Elohim | "Godly beings" |

| 8 | Bene Elohim | "Sons of Godly beings" |

| 9 | Cherubim | See Talmud Hagigah 13b |

| 10 | Ishim | "manlike beings", see Genesis 18:2, Daniel 10:5 |

Kabbalah

| The Sephirot in Jewish Kabbalah | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Category:Sephirot | ||

According to the Kabbalah as described by the Golden Dawn there are ten archangels, each commanding one of the choir of angels and corresponding to one of the Sephirot. It is similar to the Jewish angelic hierarchy.

| Rank | Choir of Angels | Translation | Archangel | Sephirah |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hayot Ha Kodesh | Holy Living Ones | Metatron | Keter |

| 2 | Ophanim | Wheels | Raziel | Chokmah |

| 3 | Erelim | Brave ones[41] | Tzaphkiel | Binah |

| 4 | Hashmallim | Glowing ones, Amber ones[42] | Tzadkiel | Chesed |

| 5 | Seraphim | Burning Ones | Khamael | Gevurah |

| 6 | Malakim | Messengers, angels | Raphael | Tipheret |

| 7 | Elohim | Godly Beings | Uriel | Netzach |

| 8 | Bene Elohim | Sons of Elohim | Michael | Hod |

| 9 | Cherubim | [43] | Gabriel | Yesod |

| 10 | Ishim | Men (man-like beings, phonetically similar to "fires") | Sandalphon | Malkuth |

셈족 신화와 이집트 신화의 관련성 편집

A comparison of the passages in Rabbinic literature which describe these and similar matters connected with the angels, spirits, etc., of ancient Hebrew mythology with Egyptian texts shows that both the Egyptians and Jews possessed many ideas in common, and all the evidence goes to prove that the latter borrowed from the former in the earliest period.

In comparatively late historical times the Egyptians introduced into their company of gods a few deities from Western Asia, but these had no effect in modifying the general character either of their religion or of their worship. The subject of comparative Egyptian and Semitic mythology is one which has yet to be worked thoroughly, not because it would supply us with the original forms of Egyptian myths and legends, but because it would show what modifications such things underwent when adopted by Semitic peoples, or at least by peoples who had Semitic blood in their veins.

Some would compare Egyptian and Semitic mythologies on the ground that the Egyptians and Semites were kinsfolk (친척들), but it must be quite clearly understood that this is pure assumption, and is only based on the statements of those who declare that the Egyptian and Semitic languages are akin. Others again have sought to explain the mythology of the Egyptians by appeals to Aryan mythology, and to illustrate the meanings of important Egyptian words in religious texts by means of Aryan etymologies, but the results are wholly unsatisfactory, and they only serve to show the futility (무용) [Page 8] of comparing the mythologies of two peoples of different race occupying quite different grades in the ladder of civilization.

The Oldest Gods Of Egypt 편집

It cannot be too strongly insisted on that all the oldest gods of Egypt are of Egyptian origin, and that the fundamental religious beliefs of the Egyptians also are of Egyptian origin, and that both the gods and the beliefs date from predynastic times, and have nothing whatever to do with the Semites or Aryans of history.

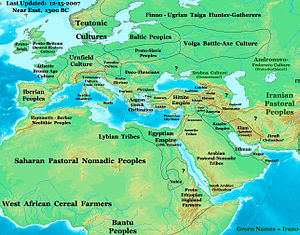

Of the origin of the Egyptian of the Palaeolithic and early Neolithic Periods, we, of course, know nothing, but it is tolerably certain that the Egyptian of the latter part of the Neolithic Period was indigenous to North-East Africa, and that a very large number of the great gods worshipped by the dynastic Egyptian were worshipped also by his predecessor in predynastic times. The conquerors of the Egyptians of the Neolithic Period who, with good reason, have been assumed to come from the East and to have been more or less akin to the Proto-Semites, no doubt brought about certain modifications in the worship of those whom they had vanquished (완파하다), but they could not have succeeded in abolishing the various gods in animal and other forms which were worshipped throughout the length and breadth (…의 전체에 걸쳐) of the country, for these continued to be venerated (공경[숭배]하다) until the time of the Ptolemies.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom (/ˌtɒləˈmeɪ.ɪk/; Πτολεμαϊκὴ βασιλεία, Ptolemaïkḕ Basileía)[44] was a Hellenistic kingdom in Egypt. It was ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty that Ptolemy I Soter founded after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC—which ended with the death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman conquest in 30 BC.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom was founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter, who declared himself Pharaoh of Egypt and created a powerful Hellenistic dynasty that ruled an area stretching from southern Syria to Cyrene and south to Nubia. Alexandria became the capital city and a center of Greek culture and trade. To gain recognition by the native Egyptian populace, they named themselves the successors to the Pharaohs. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome. Hellenistic culture continued to thrive in Egypt throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods until the Muslim conquest.

| History of Egypt | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This article is part of a series | ||||||||||

| Prehistoric Egypt pre–3100 BC | ||||||||||

| Ancient Egypt | ||||||||||

| Early Dynastic Period 3100–2686 BC | ||||||||||

| Old Kingdom 2686–2181 BC | ||||||||||

| 1st Intermediate Period 2181–2055 BC | ||||||||||

| Middle Kingdom 2055–1650 BC | ||||||||||

| 2nd Intermediate Period 1650–1550 BC | ||||||||||

| New Kingdom 1550–1069 BC | ||||||||||

| 3rd Intermediate Period 1069–664 BC | ||||||||||

| Late Period 664–332 BC | ||||||||||

| Classical Antiquity | ||||||||||

| Achaemenid Egypt 525–332 BC | ||||||||||

| Ptolemaic Egypt 332–30 BC | ||||||||||

| Roman & Byzantine Egypt 30 BC–641 AD | ||||||||||

| Sassanid Egypt 621–629 | ||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| Arab Egypt 641–969 | ||||||||||

| Fatimid Egypt 969–1171 | ||||||||||

| Ayyubid Egypt 1171–1250 | ||||||||||

| Mamluk Egypt 1250–1517 | ||||||||||

| Early Modern | ||||||||||

| Ottoman Egypt 1517–1867 | ||||||||||

| French occupation 1798–1801 | ||||||||||

| Egypt under Muhammad Ali 1805–1882 | ||||||||||

| Khedivate of Egypt 1867–1914 | ||||||||||

| Modern Egypt | ||||||||||

| British occupation 1882–1953 | ||||||||||

| Sultanate of Egypt 1914–1922 | ||||||||||

| Kingdom of Egypt 1922–1953 | ||||||||||

| Republic 1953–present | ||||||||||

The history of Ancient Egypt spans the period from the early predynastic settlements of the northern Nile Valley to the Roman conquest in 30 BC. The Pharaonic Period is dated from around 3200 BC, when Lower and Upper Egypt became a unified state, until the country fell under Greek rule in 332 BC.

Chronology

- Note

- For alternative 'revisions' to the chronology of Egypt, see Egyptian chronology.

Egypt's history is split into several different periods according to the ruling dynasty of each pharaoh. The dating of events is still a subject of research. The conservative dates are not supported by any reliable absolute date for a span of about three millennia. The following is the list according to conventional Egyptian chronology.

- Predynastic Period (Prior to 3100 BC)

- Protodynastic Period (Approximately 3100 - 3000 BC)

- Early Dynastic Period (1st–2nd Dynasties)

- Old Kingdom (3rd–6th Dynasties)

- First Intermediate Period (7th–11th Dynasties)

- Middle Kingdom (12th–13th Dynasties)

- Second Intermediate Period (14th–17th Dynasties)

- New Kingdom (18th–20th Dynasties)

- Third Intermediate Period (21st–25th Dynasties) (also known as the Libyan Period)

- Late Period (26th–31st Dynasties)

Neolithic Egypt

Neolithic period

The Nile has been the lifeline for Egyptian culture since nomadic hunter-gatherers began living along the Nile during the Pleistocene. Traces of these early people appear in the form of artifacts and rock carvings along the terraces of the Nile and in the oases. To the Egyptians the Nile meant life and the desert meant death, though the desert did provide them protection from invaders.

Along the Nile, in the 12th millennium BC, a grain-grinding culture using the earliest type of sickle blades had been replaced by another culture of hunters, fishers, and gathering people using stone tools. Evidence also indicates human habitation and cattle herding in the southwestern corner of Egypt, near the Sudan border, before 8000 BC. But according to Barbara Barich the idea of an independent bovine domestication event in Africa must be abandoned because subsequent evidence gathered over a period of thirty years has failed to corroborate this.[45] In light of this the oldest known domesticated bovine remains in Africa are from the Fayum c. 4400 BC.[46] Geological evidence and computer climate modeling studies suggest that natural climate changes around 8000 BC began to desiccate the extensive pastoral lands of northern Africa, eventually forming the Sahara (c.2500 BC).

Continued desiccation forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile more permanently and forced them to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle. However, the period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little in the way of archaeological evidence.

Predynastic period

The Nile Valley of Egypt was basically uninhabitable until the work of clearing and irrigating the land along the banks of the river was started.[47] However it appears that this clearance and irrigation was largely under way by about 6000 BC. By that time, society in the Nile Valley was already engaged in organized agriculture and the construction of large buildings in the Nile Valley.[48] At this time, Egyptians in the southwestern corner of Egypt were herding cattle and also constructing large buildings. Mortar was in use by 4000 BC. The people of the Nile Valley and on delta were self-sufficient and were raising barley and emmer (an early variety of wheat) and stored it in pits lined with reed mats.[49] They raised cattle, goats and pigs and they wove linens and baskets.[50] The Predynastic Period continues through this time, variously held to begin with the Naqada culture.

Between 5500 and 3100 BC, during Egypt's Predynastic Period, small settlements flourished along the Nile, whose delta empties into the Mediterranean Sea. By 3300 BC, just before the first Egyptian dynasty, Egypt was divided into two kingdoms, known as Upper Egypt, Ta Shemau, to the south, and Lower Egypt, Ta Mehu, to the north.[51] The dividing line was drawn roughly in the area of modern Cairo.

The Tasian culture was the next to appear in Upper Egypt. This group is named for the burials found at Der Tasa, a site on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. The Tasian culture group is notable for producing the earliest blacktop-ware, a type of red and brown pottery which has been painted black on its top and interior.[52]

The Badarian Culture, named for the Badari site near Der Tasa, followed the Tasian culture, however similarities between the two have led many to avoid differentiating between them at all. The Badarian Culture continued to produce the kind of pottery called Blacktop-ware (although its quality was much improved over previous specimens), and was assigned the Sequence Dating numbers between 21 and 29.[53] The significant difference, however, between the Tasian and Badarian culture groups which prevents scholars from completely merging the two together is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone, and thus are chalcolithic settlements, while the Tasian sites are still Neolithic, and are considered technically part of the Stone Age.[53]

The Amratian culture is named after the site of el-Amra, about 120 km south of Badari. El-Amra was the first site where this culture group was found unmingled with the later Gerzean culture group; however, this period is better attested at the Naqada site, thus it is also referred to as the Naqada I culture.[54] Black-topped ware continued to be produced, but white cross-line ware, a type of pottery which was decorated with close parallel white lines crossed by another set of close parallel white lines, began to be produced during this time. The Amratian period falls between S.D. 30 and 39 in Petrie's Sequence Dating system.[55] Trade between Upper and Lower Egypt was attested at this time, as newly excavated objects indicate. A stone vase from the north was found at el-Amra, and copper, which is not present in Egypt, was apparently imported from the Sinai, or perhaps from Nubia. Obsidian[56] and an extremely small amount of gold[55] were both definitively imported from Nubia during this time. Trade with the oases was also likely.[56]

The Gerzean Culture, named after the site of Gerza, was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation for Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture was largely an unbroken development out of Amratian Culture, starting in the delta and moving south through upper Egypt; however, it failed to dislodge Amratian Culture in Nubia.[57] Gerzean culture coincided with a significant drop in rainfall,[57] and farming produced the vast majority of food.[57] With increased food supplies, the populace adopted a much more sedentary lifestyle, and the larger settlements grew to cities of about 5,000 residents.[57] It was in this time that the city dwellers started using mud brick to build their cities.[57] Copper instead of stone was increasingly used to make tools[57] and weaponry.[58] Silver, gold, lapis, and faience were used ornamentally,[59] and the grinding palettes used for eye-paint since the Badarian period began to be adorned with relief carvings.[58]

Dynastic Egypt

|

Dynasties of Ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

|

Early dynastic period

The historical records of ancient Egypt begin with Egypt as a unified state, which occurred sometime around 3150 BC. According to Egyptian tradition Menes, thought to have unified Upper and Lower Egypt, was the first king. This Egyptian culture, customs, art expression, architecture, and social structure was closely tied to religion, remarkably stable, and changed little over a period of nearly 3000 years.

Egyptian chronology, which involves regnal years, began around this time. The conventional Egyptian chronology is the chronology accepted during the twentieth century, but it does not include any of the major revision proposals that also have been made in that time. Even within a single work, archaeologists often will offer several possible dates or even several whole chronologies as possibilities. Consequently, there may be discrepancies between dates shown here and in articles on particular rulers or topics related to ancient Egypt. There also are several possible spellings of the names. Typically, Egyptologists divide the history of pharaonic civilization using a schedule laid out first by Manetho's Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) that was written during the Ptolemaic era, during the third century BC.

Prior to the unification of Egypt, the land was settled with autonomous villages. With the early dynasties, and for much of Egypt's history thereafter, the country came to be known as the Two Lands. The rulers established a national administration and appointed royal governors.

According to Manetho, the first king was Menes, but archeological findings support the view that the first pharaoh to claim to have united the two lands was Narmer (the final king of the Protodynastic Period). His name is known primarily from the famous Narmer Palette, whose scenes have been interpreted as the act of uniting Upper and Lower Egypt.

Funeral practices for the elite resulted in the construction of mastaba tombs, which later became models for subsequent Old Kingdom constructions such as the Step pyramid.

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as spanning the period of time when Egypt was ruled by the Third Dynasty through to the Sixth Dynasty (2686 BC – 2134 BC). The royal capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom was located at Memphis, where Djoser established his court. The Old Kingdom is perhaps best known, however, for the large number of pyramids, which were constructed at this time as pharaonic burial places. For this reason, the Old Kingdom is frequently referred to as "the Age of the Pyramids." The first notable pharaoh of the Old Kingdom was Djoser (2630–2611 BC) of the Third Dynasty, who ordered the construction of a pyramid (the Step Pyramid) in Memphis' necropolis, Saqqara.

It was in this era that formerly independent ancient Egyptian states became known as nomes, ruled solely by the pharaoh. Subsequently the former rulers were forced to assume the role of governors or otherwise work in tax collection. Egyptians in this era worshiped their pharaoh as a god, believing that he ensured the annual flooding of the Nile that was necessary for their crops.

The Old Kingdom and its royal power reached their zenith under the Fourth Dynasty. Sneferu, the dynasty's founder, is believed to have commissioned at least three pyramids; while his son and successor Khufu erected the Great Pyramid of Giza, Sneferu had more stone and brick moved than any other pharaoh. Khufu (Greek Cheops), his son Khafra (Greek Chephren), and his grandson Menkaura (Greek Mycerinus), all achieved lasting fame in the construction of their pyramids. To organize and feed the manpower needed to create these pyramids required a centralized government with extensive powers, and Egyptologists believe the Old Kingdom at this time demonstrated this level of sophistication. Recent excavations near the pyramids led by Mark Lehner have uncovered a large city which seems to have housed, fed and supplied the pyramid workers. Although it was once believed that slaves built these monuments, a theory based on the biblical Exodus story, study of the tombs of the workmen, who oversaw construction on the pyramids, has shown they were built by a corvée of peasants drawn from across Egypt. They apparently worked while the annual Nile flood covered their fields, as well as a very large crew of specialists, including stone cutters, painters, mathematicians and priests.

The Fifth Dynasty began with Userkhaf (starting c. 2495 BC) and was marked by the growing importance of the cult of sun god Ra. Consequently less efforts were devoted to the construction of pyramid complexes than during the 4th dynasty and more to the construction of sun temples in Abusir. The decoration of pyramid complexes grew more elaborate during the dynasty and its last king, Unas, was the first to have the pyramid texts inscribed in his pyramid. Egypt's expanding interests in trade goods such as ebony, incense such as myrrh and frankincense, gold, copper and other useful metals compelled the ancient Egyptians to navigate of the open seas. Evidence from the pyramid of Sahure, second king of the dynasty, shows that a regular trade existed with the Syrian cost to procure cedar wood. Pharaohs also launched expeditions to the famed Land of Punt, possibly in modern day Ethiopia and Somalia, for ebony, ivory and aromatic resins.

During the sixth dynasty (2345–2181 BC), the power of pharaohs gradually weakened in favor of powerful nomarchs (regional governors). These no longer belonged to the royal family and their charge became hereditary, thus creating local dynasties largely independent from the central authority of the pharaoh. Internal disorders set in during the incredibly long reign of Pepi II (2278–2184 BC) towards the end of the dynasty. His death, certainly well past that of his intended heirs, might have created succession struggles and the country slipped into civil wars mere decades after the close of Pepi II's reign. The final blow came when a severe drought affected the region which resulted from a drastic drop in precipitation during the 22nd century BC, producing consistently low Nile flood levels.[60] The result was the collapse of the Old Kingdom followed by decades of famine and strife.

First Intermediate Period

After the fall of the Old Kingdom came a roughly 200-year stretch of time known as the First Intermediate Period, which is generally thought to include a relatively obscure set of pharaohs running from the end of the Sixth to the Tenth, and most of the Eleventh Dynasty. Most of these were likely local monarchs who did not hold much power outside of their own limited domain, and none held power over the whole of Egypt.

While there are next to no official records covering this period, there are a number of fictional texts known as Lamentations from the early period of the subsequent Middle Kingdom that may shed some light on what happened during this period. Some of these texts reflect on the breakdown of rule, others allude to invasion by "Asiatic bowmen". In general the stories focus on a society where the natural order of things in both society and nature was overthrown.

It is also highly likely that it was during this period that all of the pyramid and tomb complexes were robbed. Further lamentation texts allude to this fact, and by the beginning of the Middle Kingdom mummies are found decorated with magical spells that were once exclusive to the pyramid of the kings of the sixth dynasty.

By 2160 BC a new line of pharaohs (the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties) consolidated Lower Egypt from their capital in Herakleopolis Magna. A rival line (the Eleventh Dynasty) based at Thebes reunited Upper Egypt and a clash between the two rival dynasties was inevitable. Around 2055 BC the Theban forces defeated the Heracleopolitan Pharaohs, reunited the Two Lands. The reign of its first pharaoh, Mentuhotep II marks the beginning of the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Fourteenth Dynasty, roughly between 2030 BC and 1640 BC.

The period comprises two phases, the 11th Dynasty, which ruled from Thebes and the 12th Dynasty onwards which was centered around el-Lisht. These two dynasties were originally considered to be the full extent of this unified kingdom, but historians now[61] consider the 13th Dynasty to at least partially belong to the Middle Kingdom.

The earliest pharaohs of the Middle Kingdom traced their origin to a nomarch of Thebes, "Intef the Great, son of Iku", who is mentioned in a number of contemporary inscriptions. However, his immediate successor Mentuhotep II is considered the first pharaoh of this dynasty.

An inscription carved during the reign of Wahankh Intef II shows that he was the first of this dynasty to claim to rule over the whole of Egypt, a claim which brought the Thebeans into conflict with the rulers of Herakleopolis Magna, the Tenth Dynasty. Intef undertook several campaigns northwards, and captured the important nome of Abydos.

Warfare continued intermittently between the Thebean and Heracleapolitan dynasties until the 14th regnal year of Nebhetepra Mentuhotep II, when the Herakleopolitans were defeated, and the Theban dynasty began to consolidate their rule. Mentuhotep II is known to have commanded military campaigns south into Nubia, which had gained its independence during the First Intermediate Period. There is also evidence for military actions against Palestine. The king reorganized the country and placed a vizier at the head of civil administration for the country.

Mentuhotep IV was the final pharaoh of this dynasty, and despite being absent from various lists of pharaohs, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat that record expeditions to the Red Sea coast and to quarry stone for the royal monuments. The leader of this expedition was his vizier Amenemhat, who is widely assumed to be the future pharaoh Amenemhet I, the first king of the 12th Dynasty. Amenemhet is widely assumed by some Egyptologists to have either usurped the throne or assumed power after Mentuhotep IV died childless.

Amenemhat I built a new capital for Egypt, known as Itjtawy, thought to be located near the present-day el-Lisht, although the chronicler Manetho claims the capital remained at Thebes. Amenemhat forcibly pacified internal unrest, curtailed the rights of the nomarchs, and is known to have at launched at least one campaign into Nubia. His son Senusret I continued the policy of his father to recapture Nubia and other territories lost during the First Intermediate Period. The Libyans were subdued under his forty-five year reign and Egypt's prosperity and security were secured.

Senusret III (1878 BC – 1839 BC) was a warrior-king, leading his troops deep into Nubia, and built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish Egypt's formal boundaries with the unconquered areas of its territory. Amenemhet III (1860 BC – 1815 BC) is considered the last great pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom.

Egypt's population began to exceed food production levels during the reign of Amenemhat III, who then ordered the exploitation of the Fayyum and increased mining operations in the Sinaï desert. He also invited Asiatic settlers to Egypt to labor on Egypt's monuments. Late in his reign the annual floods along the Nile began to fail, further straining the resources of the government. The Thirteenth Dynasty and Fourteenth Dynasty witnessed the slow decline of Egypt into the Second Intermediate Period in which some of the Asiatic settlers of Amenemhat III would grasp power over Egypt as the Hyksos.

Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when Ancient Egypt once again fell into disarray between the end of the Middle Kingdom, and the start of the New Kingdom. This period is best known as the time the Hyksos (an Asiatic people) made their appearance in Egypt, the reigns of its kings comprising the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties.

The Thirteenth Dynasty proved unable to hold onto the long land of Egypt, and a provincial ruling family located in the marshes of the western Delta at Xois broke away from the central authority to form the Fourteenth Dynasty. The splintering of the land accelerated after the reign of the Thirteenth Dynasty king Neferhotep I.

The Hyksos first appear during the reign of the Thirteenth Dynasty pharaoh Sobekhotep IV, and by 1720 BC took control of the town of Avaris. The outlines of the traditional account of the "invasion" of the land by the Hyksos is preserved in the Aegyptiaca of Manetho, who records that during this time the Hyksos overran Egypt, led by Salitis, the founder of the Fifteenth Dynasty. In the last decades, however, the idea of a simple migration, with little or no violence involved, has gained some support.[62] Under this theory, the Egyptian rulers of 13th Dynasty were unable to stop these new migrants from travelling to Egypt from Asia because they were weak kings who were struggling to cope with various domestic problems including possibly famine.

The Hyksos princes and chieftains ruled in the eastern Delta with their local Egyptian vassals. The Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty rulers established their capital and seat of government at Memphis and their summer residence at Avaris.

The Hyksos kingdom was centered in the eastern Nile Delta and Middle Egypt and was limited in size, never extending south into Upper Egypt, which was under control by Theban-based rulers. Hyksos relations with the south seem to have been mainly of a commercial nature, although Theban princes appear to have recognized the Hyksos rulers and may possibly have provided them with tribute for a period.

Around the time Memphis fell to the Hyksos, the native Egyptian ruling house in Thebes declared its independence from the vassal dynasty in Itj-tawy and set itself up as the Seventeenth Dynasty. This dynasty was to prove the salvation of Egypt and would eventually lead the war of liberation that drove the Hyksos back into Asia. The two last kings of this dynasty were Tao II the Brave and Kamose. Ahmose I completed the conquest and expulsion of the Hyksos from the delta region, restored Theban rule over the whole of Egypt and successfully reasserted Egyptian power in its formerly subject territories of Nubia and Canaan.[63] His reign marks this beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom period.

New Kingdom

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

Eighteenth Dynasty

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known Pharaohs ruled at this time. Hatshepsut was a pharaoh at this time. Hatshepsut is unusual as she was a female pharaoh, a rare occurrence in Egyptian history. She was an ambitious and competent leader, extending Egyptian trade south into present-day Somalia and north into the Mediterranean. She ruled for twenty years through a combination of widespread propaganda and deft political skill. Her co-regent and successor Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success. Late in his reign he ordered her name hacked out from her monuments. He fought against Asiatic people and was the most successful of Egyptian pharaohs. Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak including the Luxor temple which consisted of two pylons, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Ma'at.

Nineteenth Dynasty

Ramesses I reigned for two years and was succeeded by his son Seti I. Seti I carried on the work of Horemheb in restoring power, control, and respect to Egypt. He also was responsible for creating the temple complex at Abydos.

Arguably Ancient Egypt's power as a nation-state peaked during the reign of Ramesses II ("the Great") of the 19th Dynasty. He reigned for 67 years from the age of 18 and carried on his immediate predecessor's work and created many more splendid temples, such as that of Abu Simbel on the Nubian border. He sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by 18th Dynasty Egypt. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II and was caught in history's first recorded military ambush. Ramesses II was famed for the huge number of children he sired by his various wives and concubines; the tomb he built for his sons (many of whom he outlived) in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt.

His immediate successors continued the military campaigns, though an increasingly troubled court complicated matters. Ramesses II was succeeded by his son Merneptah and then by Merenptah's son Seti II. Seti II's throne seems to have been disputed by his half-brother Amenmesse, who may have temporarily ruled from Thebes. Upon his death, Seti II son Siptah, who may have been afflicted with polio during his life, was appointed to the throne by Chancellor Bay, an Asiatic commoner who served as vizier behind the scenes. At Siptah's early death, the throne was assumed by Twosret, the dowager queen of Seti II (and possibly Amenmesse's sister). A period of anarchy at the end of Twosret's short reign saw a native reaction to foreign control leading to the execution of the chancellor, and placing Setnakhte on the throne, establishing the Twentieth Dynasty.

Twentieth Dynasty

The last "great" pharaoh from the New Kingdom is widely regarded to be Ramesses III, the son of Setnakhte who reigned three decades after the time of Ramesses II. In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea People, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. He claimed that he incorporated them as subject people and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. He was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[64]

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned.[65] Something in the air prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC.[66] One proposed cause is the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland, but the dating of that event remains in dispute.

Following Ramesses III's death there was endless bickering between his heirs. Three of his sons would go on to assume power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption. The power of the last pharaoh, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the effective defacto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death. Smendes would eventually found the Twenty-First dynasty at Tanis.

Third Intermediate Period

After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor Smendes ruled from the city of Tanis in the north, while the High Priests of Amun at Thebes had effective rule of the south of the country, whilst still nominally recognizing Smendes as king.[67] In fact, this division was less significant than it seems, since both priests and pharaohs came from the same family. Piankh, assumed control of Upper Egypt, ruling from Thebes, with the northern limit of his control ending at Al-Hibah. (The High Priest Herihor had died before Ramesses XI, but also was an all-but-independent ruler in the latter days of the king's reign.) The country was once again split into two parts with the priests in Thebes and the Pharaohs at Tanis. Their reign seems to be without any other distinction, and they were replaced without any apparent struggle by the Libyan kings of the Twenty-Second Dynasty.

Egypt has long had ties with Libya, and the first king of the new dynasty, Shoshenq I, was a Meshwesh Libyan, who served as the commander of the armies under the last ruler of the Twenty-First Dynasty, Psusennes II. He unified the country, putting control of the Amun clergy under his own son as the High Priest of Amun, a post that was previously a hereditary appointment. The scant and patchy nature of the written records from this period suggest that it was unsettled. There appear to have been many subversive groups, which eventually led to the creation of the Twenty-Third Dynasty, which ran concurrent with the latter part of the Twenty-Second Dynasty. The country was reunited by the Twenty-Second Dynasty founded by Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC), who descended from Meshwesh immigrants, originally from Ancient Libya. This brought stability to the country for well over a century. After the reign of Osorkon II the country had again splintered into two states with Shoshenq III of the Twenty-Second Dynasty controlling Lower Egypt by 818 BC while Takelot II and his son (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt.

After the withdrawal of Egypt from Nubia at the end of the New Kingdom, a native dynasty took control of Nubia. Under king Piye, the Nubian founder of Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, the Nubians pushed north in an effort to crush his Libyan opponents ruling in the Delta. Piye managed to attain power as far as Memphis. His opponent Tefnakhte ultimately submitted to him, but he was allowed to remain in power in Lower Egypt and founded the short-lived Twenty-Fourth Dynasty at Sais. The Kushite kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and political instability and defeated the combined might of several native-Egyptian rulers such as Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, and Tefnakht of Sais. Piye established the Nubian Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and appointed the defeated rulers to be his provincial governors. He was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa. Taharqa reunited the "Two lands" of Northern and Southern Egypt and created an empire that was as large as it had been since the New Kingdom. The 25th dynasty ushered in a renaissance period for Ancient Egypt.[68] Religion, the arts, and architecture were restored to their glorious Old, Middle, and New Kingdom forms. Pharaohs, such as Taharqa, built or restored temples and monuments throughout the Nile valley, including at Memphis, Karnak, Kawa, Jebel Barkal, etc.[69] It was during the 25th dynasty that the Nile valley saw the first widespread construction of pyramids (many in modern Sudan) since the Middle Kingdom.[70] [71] [72]

The international prestige of Egypt declined considerably by this time. The country's international allies had fallen under the sphere of influence of Assyria and from about 700 BC the question became when, not if, there would be war between the two states. Taharqa's reign and that of his successor, Tanutamun, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians against whom there were numerous victories, but ultimately Thebes was occupied and Memphis sacked.

Late Period

From 671 BC on, Memphis and the Delta region became the target of many attacks from the Assyrians, who expelled the Nubians and handed over power to client kings of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Psamtik I was the first to be recognized as the king of the whole of Egypt, and he brought increased stability to the country during a 54-year reign from the new capital of Sais. Four successive Saite kings continued guiding Egypt successfully and peacefully from 610-526 BC, keeping the Babylonians away with the help of Greek mercenaries.

By the end of this period a new power was growing in the Near East: Persia. The pharaoh Psamtik III had to face the might of Persia at Pelusium; he was defeated and briefly escaped to Memphis, but ultimately was captured and then executed.

Persian domination

Achaemenid Egypt can be divided into three eras: the first period of Persian occupation when Egypt became a satrapy, followed by an interval of independence, and the second and final period of occupation.

The Persian king Cambyses assumed the formal title of Pharaoh, called himself Mesuti-Re ("Re has given birth"), and sacrificed to the Egyptian gods. He founded the Twenty-seventh dynasty. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.

Cambyses' successors Darius I the Great and Xerxes pursued a similar policy, visited the country, and warded off an Athenian attack. It is likely that Artaxerxes I and Darius II visited the country as well, although it is not attested in our sources, and did not prevent the Egyptians from feeling unhappy.

During the war of succession after the reign of Darius II, which broke out in 404, they revolted under Amyrtaeus and regained their independence. This sole ruler of the Twenty-eighth dynasty died in 399, and power went to the Twenty-ninth dynasty. The Thirtieth Dynasty was established in 380 BC and lasted until 343 BC. Nectanebo II was the last native king to rule Egypt.

Artaxerxes III (358–338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief period (343–332 BC). In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and then the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

Ptolemaic dynasty

In 332 BC Alexander III of Macedon conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians. He was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. He visited Memphis, and went on a pilgrimage to the oracle of Amun at the Oasis of Siwa. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun. He conciliated the Egyptians by the respect which he showed for their religion, but he appointed Greeks to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Persian Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander never returned to Egypt.

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death. Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV. However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322 BC-301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of King. As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life.[73][74] Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome.

Indigenous Beliefs 편집

정복자들의 종교는 토착 종교에 크게 영향을 미치지 못하였다 편집

The conquerors of the Egyptians of the Neolithic Period who, with good reason, have been assumed to come from the East and to have been more or less akin to the Proto-Semites, no doubt brought about certain modifications in the worship of those whom they had vanquished (완파하다), but they could not have succeeded in abolishing the various gods in animal and other forms which were worshipped throughout the length and breadth (…의 전체에 걸쳐) of the country, for these continued to be venerated (공경[숭배]하다) until the time of the Ptolemies.

We have at present no means of knowing how far the religious beliefs of the conquerors influenced the conquered peoples of Egypt, but viewed in the light of well-ascertained facts it seems tolerably certain that no great change took place in the views which the indigenous peoples held concerning their gods as the result of the invasion of foreigners, and that if any foreign gods were introduced into the company of indigenous, predynastic gods, they were either quickly assimilated to or wholly absorbed by them.

이집트 신들은 이집트 역사 전반에서 대체로 변화없이 계속되었다 편집

Speaking generally, the gods of the Egyptians remained unchanged throughout all the various periods of the history of Egypt, and the minds of the people seem always to have had a tendency towards the maintenance of old forms of worship, and to the preservation of the ancient texts in which such forms were prescribed and old beliefs were enshrined (…에 명시되어 있는). The Egyptians never forgot the ancient gods of the country, and it is typical of the spirit of conservatism which they displayed in most things that even in the Roman [Page 9] Period (Roman & Byzantine Egypt 30 BC–641 AD) pious folk among them were buried with the same prayers and with the same ceremonies that had been employed at the burial of Egyptians nearly five thousand years before.

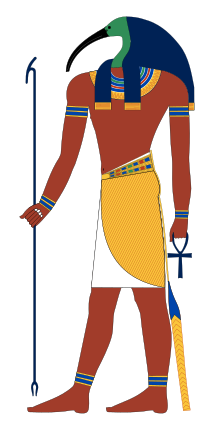

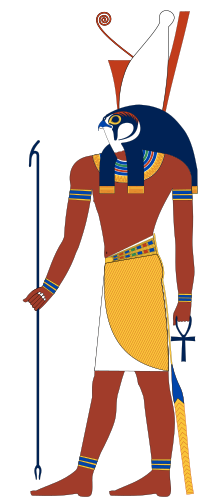

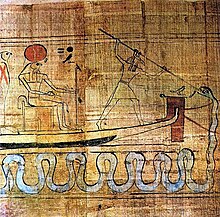

아누비스 · 토트 · 오시리스 · 호루스 편집