사용자:배우는사람/문서:963~1,020행: 여신들과 남자들의 교합

963~1,020행: 여신들과 남자들의 교합 편집

OF GODDESSES AND MEN

[963] And now farewell, you dwellers on Olympus (올림포스 산) and you islands and continents and thou briny sea within. Now sing the company of goddesses, sweet-voiced Muses (무사: 제우스와 므네모시네의 아홉 딸, 문학 · 과학 · 예술의 여신들) of Olympus, daughter of Zeus who holds the aegis (아이기스: 이지스, 제우스의 방패), -- even those deathless one who lay with mortal men and bare children like unto gods.

데메테르와 이아시온의 자녀: 플루토스 편집

[969] Demeter (데메테르: 도데카테온, 올림포스 12신, 크로노스와 레아의 딸, 제우스의 네 번째 아내, 곡물과 수확의 여신), bright goddess, was joined in sweet love with the hero Iasion (이아시온: 제우스와 엘렉트라의 아들, 다르다노스의 형제) in a thrice-ploughed fallow in the rich land of Crete, and bare

- Plutus(플루토스: 이아시온과 데메테르의 아들, 부의 신), a kindly god who goes everywhere over land and the sea's wide back, and him who finds him and into whose hands he comes he makes rich, bestowing great wealth upon him.

Eirene with the infant Ploutos: Roman copy after Kephisodotos' votive statue, c. 370BCE, in the Agora, Athens - In Greek mythology, Iasion (Ἰασίων, gen.: Ἰασίωνος) or Iasus (Ἴασος, gen.: Ἰάσου) or Eetion (Ἠετίων) was usually the son of the nymph Electra and Zeus and brother of Dardanus, although other possible parentage included Zeus and Hemera or Corythus and Electra.

- Iasion founded the mystic rites on the island of Samothrace. With Demeter, he was the father of twin sons named Ploutos and Philomelus, and another son named Korybas.

- At the marriage of Cadmus and Harmonia, Iasion was lured by Demeter away from the other revelers. They had intercourse as Demeter lay on her back in freshly plowed furrow. When they rejoined the celebration, Zeus guessed what had happened because of the mud on Demeter's backside, and promptly killed Iasion with a thunderbolt.[1] [2] Some versions of this myth conclude with Iasion and the agricultural hero Triptolemus then becoming the Gemini constellation.

- Ploutos (Πλοῦτος, "Wealth"), usually Romanized as Plutus, was the god of wealth in ancient Greek religion and myth. He was the son of Demeter[3] and the demigod Iasion, with whom she lay in a thrice-ploughed field. In the theology of the Eleusinian Mysteries he was regarded as the Divine Child. His relation to the classical ruler of the underworld Plouton (Latin Pluto), with whom he is often conflated, is complex, as Pluto was also a god of riches.

카드모스와 하르모니아의 자녀: 이노 · 세멜레 · 아가우에 · 아우토노에 · 폴리도로스 편집

[975] And Harmonia (하르모니아: 아레스와 아프로디테의 딸, 혹은 제우스와 엘렉트라의 딸, 조화와 일치의 여신), the daughter of golden Aphrodite, bare to Cadmus (카드모스: 페니키아의 왕자, 그리스의 테베를 건설한 자)

- Ino (이노: 카드모스와 하르모니아의 딸) and

- Semele (세멜레: 인간, 후에 여신 티오네(Thyone)가 됨, 카드모스와 하르모니아의 딸, 디오니소스의 어머니) and

- fair-cheeked Agave (아가우에 또는 아가베: 카드모스와 하르모니아의 딸) and

- Autonoe (아우토노에: 카드모스와 하르모니아의 딸) whom long haired Aristaeus (아리스타이오스: 아폴론과 키레네의 아들) wedded, and

- Polydorus (폴리도로스: 카드모스와 하르모니아의 아들) also in rich-crowned Thebe.

Statue of Harmonia in the Harmony Society gardens in Old Economy Village, Pennsylvania.

- In Greek mythology, Harmonia (Ἁρμονία) is the immortal goddess of harmony and concord. Her Roman counterpart is Concordia, and her Greek opposite is Eris, whose Roman counterpart is Discordia.

- Origins

- According to one account, she is the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite; By yet another account, Harmonia was from Samothrace and was the daughter of Zeus and Electra, her brother Iasion being the founder of the mystic rites celebrated on the island. Finally, Harmonia is rationalized as closely allied to Aphrodite Pandemos, the love that unites all people, the personification of order and civic unity, corresponding to the Roman goddess Concordia.

- Almost always, Harmonia is the wife of Cadmus. With Cadmus, she was the mother of Ino, Polydorus, Autonoë, Agave and Semele. Their youngest[4] son was Illyrius.[5]

- Those who described Harmonia as a Samothracian related that Cadmus, on his voyage to Samothrace, after being initiated in the mysteries, perceived Harmonia, and carried her off with the assistance of Athena. When Cadmus was obliged to quit Thebes, Harmonia accompanied him. When they came to the Encheleans, they assisted them in their war against the Illyrians, and conquered the enemy. Cadmus then became king of the Illyrians, but afterwards he was turned into a serpent. Harmonia, in her grief stripped herself, then begged Cadmus to come to her. As she was embraced by the serpent Cadmus in a pool of wine, the gods then turned her into a serpent, unable to stand watching her in her dazed state.[6]

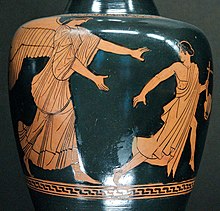

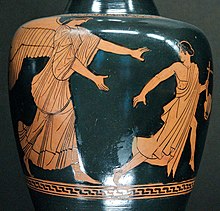

Pentheus torn apart by Agave and Ino. Attic red-figure lekanis (cosmetics bowl) lid, ca. 450-425 BCE (Louvre) - In Greek mythology Ino (/ˈaɪnoʊ/ Ἰνώ [iː'nɔː][7]) was a mortal queen of Thebes, who after her death and transfiguration was worshiped as a goddess under her epithet Leucothea, the "white goddess." Alcman called her "Queen of the Sea" (θαλασσομέδουσα),[8] which, if not hyperbole, would make her a doublet of Amphitrite.

- In her mortal self, Ino, the second wife of the Minyan king Athamas, the mother of Learches and Melicertes, daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia[9] and stepmother of Phrixus and Helle, was one of the three sisters of Semele, the mortal woman of the house of Cadmus who gave birth to Dionysus. The three sisters were Agave, Autonoë and Ino, who was a surrogate for the divine nurses of Dionysus: "Ino was a primordial Dionysian woman, nurse to the god and a divine maenad" (Kerenyi 1976:246).

- Maenads were reputed to tear their own children limb from limb in their madness. In the back-story to the heroic tale of Jason and the Golden Fleece, Phrixus and Helle, twin children of Athamas and Nephele, were hated by their stepmother, Ino. Ino hatched a devious plot to get rid of the twins, roasting all the crop seeds of Boeotia so they would not grow.[10] The local farmers, frightened of famine, asked a nearby oracle for assistance. Ino bribed the men sent to the oracle to lie and tell the others that the oracle required the sacrifice of Phrixus. Athamas reluctantly agreed. Before he was killed though, Phrixus and Helle were rescued by a flying golden ram sent by Nephele, their natural mother. Helle fell off the ram into the Hellespont (which was named after her, meaning Sea of Helle) and drowned, but Phrixus survived all the way to Colchis, where King Aeetes took him in and treated him kindly, giving Phrixus his daughter, Chalciope, in marriage. In gratitude, Phrixus gave the king the golden fleece of the ram, which Aeetes hung in a tree in his kingdom.

- Later, Ino raised Dionysus, her nephew, son of her sister Semele,[11] causing Hera's intense jealousy. In vengeance, Hera struck Athamas with insanity. Athamas went mad, slew one of his sons, Learchus, thinking he was a ram, and set out in frenzied pursuit of Ino. To escape him Ino threw herself into the sea with her son Melicertes. Both were afterwards worshipped as marine divinities, Ino as Leucothea ("the white goddess"), Melicertes as Palaemon. Alternatively, Ino was also stricken with insanity and killed Melicertes by boiling him in a cauldron, then took the cauldron and jumped into the sea with it. A sympathetic Zeus did not want Ino to die, and transfigured her and Melicertes as Leucothea and Palaemon.

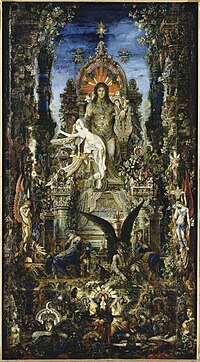

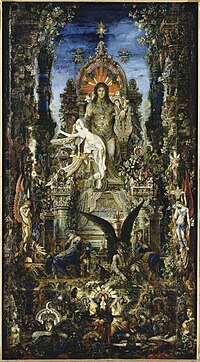

Jupiter and Semele (1894-95), by Gustave Moreau - Semele (/ˈsɛməliː/; Σεμέλη, Semelē), in Greek mythology, daughter of the Boeotian hero Cadmus and Harmonia, was the mortal mother[12] of Dionysus by Zeus in one of his many origin myths. The name "Semele", like other elements of Dionysiac cult (e.g., thyrsus and dithyramb), is not Greek[13] but Thraco-Phrygian,[14] derived from a PIE root meaning "earth".[15][16]

- It seems that certain elements of the cult of Dionysos and Semele were adopted by the Thracians from the local populations when they moved to Asia Minor, where they were named Phrygians.[17] These were transmitted later to the Greek colonists. Herodotus, who gives the account of Cadmus, estimates that Semele lived sixteen hundred years before his time, or around 2000 BCE[18] In Rome, the goddess Stimula was identified as Semele.

- In Greek mythology, Agave (/ˈæɡəvi/; Ἀγαύη, Agauē, "illustrious") was the daughter of Cadmus, the king and founder of the city of Thebes, Greece, and of the goddess Harmonia. Her sisters were Autonoë, Ino and Semele, and her brother was Polydorus.[19] She married Echion, one of the five Spartoi, and was the mother of Pentheus, a king of Thebes. She also had a daughter, Epirus. She was a Maenad, a follower of Dionysus (also known as Bacchus in Roman mythology).

- In Euripides' play, The Bacchae, Theban Maenads murdered King Pentheus after he banned the worship of Dionysus because he denied Dionysus' divinity. Dionysus, Pentheus' cousin, himself lured Pentheus to the woods, Pentheus wanting to see what he thought were the sexual activities of the women, where the Maenads tore him apart and his corpse was mutilated by his own mother, Agave. She, thinking he was a lion, carried his head on a stick back to Thebes, only realizing what had happened after meeting Cadmus.

- This murder also served as Dionysus' vengeance on Agave (and her sisters Ino and Autonoë). Semele, during her pregnancy with Dionysus, was destroyed by the sight of the splendor of Zeus. Her sisters spread the report that she had only endeavored to conceal unmarried sex with a mortal man, by pretending that Zeus was the father of her child, and said that her destruction was a just punishment for her falsehood. This calumny was afterwards most severely avenged upon Agave. For, after Dionysus, the son of Semele, had traversed the world, he came to Thebes and sent the Theban women mad, compelling them to celebrate his Dionysiac festivals on Mount Cithaeron. Pentheus, wishing to prevent or stop these riotous proceedings, was persuaded by a disguised Dionysus to go himself to Cithaeron, but was torn to pieces there by his own mother Agave, who in her frenzy believed him to be a wild lion.[20][21]

- For this transgression, according to Hyginus,[22] Agave was exiled from Thebes and fled to Illyria to marry King Lycotherses, and then killed him in order to gain the city for her father Cadmus. This account, however, is manifestly transplaced by Hyginus, and must have belonged to an earlier part of the story of Agave.[23]

- Other characters

- Agave is also the name of three more minor characters in Greek mythology.

- In Greek mythology, Autonoë (/ɔːˈtɒnoʊ.i/; Αὐτονόη) was a daughter of Cadmus, founder of Thebes, Greece, and the goddess Harmonia. She was the wife of Aristaeus and mother of Actaeon and possibly Macris.[30] In Euripides' play, The Bacchae, she and her sisters were driven into a bacchic frenzy by the god Dionysus (her nephew) when Pentheus, the king of Thebes, refused to allow his worship in the city. When Pentheus came to spy on their revels, Agave, the mother of Pentheus and Autonoë's sister, spotted him in a tree. They tore him to pieces.

- In Greek mythology, Polydorus (Πολύδωρος) was the eldest son of Cadmus and Harmonia and king of Thebes. His sisters were Semele, Ino, Agave, and Autonoë.

- Upon the death of Cadmus, Pentheus, the son of Echion and Agave, the daughter of Cadmus, ruled Thebes for a short time until Dionysus prompted Agave to kill Pentheus.[32] Polydorus then succeeded Pentheus as king of Thebes and married Nycteïs, the daughter of Nycteus. When their son Labdacus was still young, Polydorus died of unknown causes, leaving Nycteus as his regent.[33] In Pausanias's history, Polydorus' rule began when his father abdicated, but this is the only source for such a timeline.[34]

- Thebe (Θήβη) is a feminine name mentioned several times in Greek mythology, in accounts that imply multiple female characters, four of whom are said to have had three cities named Thebes after them:

- Thebe, daughter of Asopus and Metope,[35][36] who became wife of Zethus, and gave her name to Boeotian Thebes.[37] She is also said to have consorted with Zeus.[38]

- Thebe, daughter of Zeus and Iodame, given in marriage to Ogygus.[39]

- Thebe, daughter of Prometheus, and also a possible eponym of the Boeotian Thebes.[40]

- Thebe, daughter of Cilix and wife of Corybas (son of Cybele).[41]

- Thebe, eponym of Thebes, Egypt.[42] She was the daughter of either Nilus, Epaphus, Proteus, or Libys;[43] rare versions of the myth make her a consort of Zeus and mother of Aegyptus[39] or Heracles.[44]

- Thebe, daughter of the Pelasgian Adramys, the eponym of Adramyttium, or of the river god Granicus. She married Heracles, who named Hypoplacian Thebes after her.[45]

- Thebe, daughter of Zeus and Megacleite, sister of Locrus.[46]

크리사오르와 칼리오레의 자녀: 게리온 편집

[979] And the daughter of Ocean (오케아노스, 티탄, 거대한 강의 남신, 세계해의 남신, 우라노스와 가이아의 아들, 3000 오케아니스의 아버지), Callirrhoe (칼리로에: 나이아스, 물의 요정, 세 명의 남편: 크리사오르 · 닐로스 · 포세이돈) was joined in the love of rich Aphrodite (아프로디테: 미와 사랑의 여신, 비너스) with stout hearted Chrysaor (크리사오르: 포세이돈과 메두사의 아들, 페가수스의 형제) and bare a son who was the strongest of all men,

- Geryones (게리온: 크리사오르와 칼리로에의 아들, 메두사의 손자, 3개의 머리와 몸을 가진 괴물), whom mighty Heracles killed in sea-girt Erythea for the sake of his shambling oxen.

- In Greek mythology, Callirrhoe (Ancient Greek: Καλλιρρόη, meaning "Beautiful Flow," often written Callirrhoë) was a naiad. She was the daughter of Oceanus and Tethys.[47][48] She had three husbands, Chrysaor, Neilus and Poseidon. She was one of the three ancestors of the Tyrians, along with Abarbarea and Drosera.[49] Jupiter's moon Callirrhoe is named after her.

- Children

| Chrysaor | |

|---|---|

Khrysaor, son of the Gorgon at the pediment of the Temple of Artemis in Corfu | |

| Consort | Callirrhoe |

| Parents | Poseidon and Medusa |

| Siblings | Pegasus |

| Children | Geryon and Echidna |

- In Greek mythology, Chrysaor (Χρυσάωρ, Khrusaōr; English translation: "He who has a golden armament"), the brother of the winged horse Pegasus, was often depicted as a young man, the son of Poseidon and Medusa. Chrysaor and Pegasus were not born until Perseus chopped off Medusa's head.[57]

- Medusa, one of the Gorgon sisters, the most beautiful, and the only mortal one, offended Athena by lying with Poseidon in the Temple of Athena. As punishment, Athena turned her hair into snakes. Chrysaor and Pegasus were said to be born from the drops of Medusa's blood which fell in the sea; others say that they sprang from Medusa's neck as Perseus beheaded her, a "higher" birth (such as the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus). Chrysaor is said to have been king of Iberia (Andorra, Gibraltar, Spain, and Portugal).

Chrysaor, married to Callirrhoe, daughter of glorious Oceanus, was father to the triple-headed Geryon, but Geryon was killed by the great strength of Heracles at sea-circled Erytheis beside his own shambling cattle on that day when Heracles drove those broad-faced cattle toward holy Tiryns, when he crossed the stream of Okeanos and had killed Orthos and the oxherd Eurytion out in the gloomy meadow beyond fabulous Okeanos.

- In art Chrysaor's earliest appearance seems to be on the great pediment of the early 6th century BC Doric Temple of Artemis at Corfu, where he is shown beside his mother, Medusa.[출처 필요]

- In Greek mythology, Geryon /ˈdʒɪəriən/ or /ˈɡɛriən/[58] (Γηρυών; genitive: Γηρυόνος)[59] son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe and grandson of Medusa, was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides in the far west of the Mediterranean. A more literal-minded later generation of Greeks associated the region with Tartessos in southern Iberia.[60]

- Geryon was often described as a monster with human faces. According to Hesiod[61] Geryon had one body and three heads, whereas the tradition followed by Aeschylus gave him three bodies.[62] A lost description by Stesichoros said that he has six hands and six feet and is winged;[63] there are some mid-sixth-century Chalcidian vases portraying Geryon as winged. Some accounts state that he had six legs as well while others state that the three bodies were joined to one pair of legs. Apart from these bizarre features, his appearance was that of a warrior. He owned a two-headed hound named Orthrus, which was the brother of Cerberus, and a herd of magnificent red cattle that were guarded by Orthrus, and a herder Eurytion, son of Erytheia.[64]

티토노스와 에오스의 자녀: 멤논 · 에마티온 편집

[984] And Eos (에오스: 새벽의 여신, 테이아와 히페리온의 딸) bare to Tithonus (티토노스: 트로이 왕 라오메돈과 물의 요정 스트리모의 아들, 에오스의 연인)

- brazen-crested Memnon (멤논: 티토노스와 에오스의 아들), king of the Ethiopians, and the

- Lord Emathion (에마티온: 티토노스와 에오스의 아들).

- In Greek mythology, Ēōs (/ˈiːɒs/; Ἠώς, or Ἕως, Éōs, "dawn", 발음 [ɛːɔ̌ːs] or [éɔːs]; also Αὔως, Aýōs in Aeolic) is a Titaness and the goddess[65][출처 필요] of the dawn, who rose each morning from her home at the edge of the Oceanus.

- Lovers and children

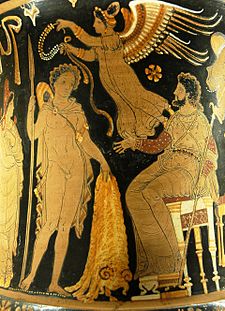

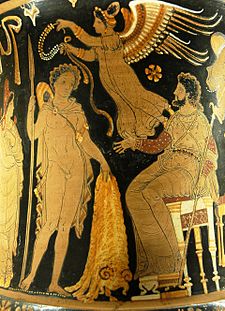

Eos in her chariot flying over the sea, red-figure krater from South Italy, 430–420 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlungen - According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, Eos consorted with the war god Ares and was thereupon cursed with unsatisfiable sexual desire by the jealous Aphrodite.[66] This caused her to abduct a number of handsome young men, most notably Cephalus, Tithonus, Orion and Cleitus. The good-looking Cleitus was made immortal by her.[67] She also asked for Tithonus to be made immortal, but forgot to ask for eternal youth, which resulted in him living forever as a helpless old man.[68]

Eos and the slain Memnon on an Attic red-figure cup, ca. 490–480 BCE, the so-called "Memnon Pietà" found at Capua (Louvre). - According to Hesiod[69] by Tithonus Eos had two sons, Memnon and Emathion. Memnon fought among the Trojans in the Trojan War and was slain. Her image with the dead Memnon across her knees, like Thetis with the dead Achilles are icons that inspired the Christian Pietà.

- The abduction of Cephalus had special appeal for an Athenian audience because Cephalus was a local boy,[70] and so this myth element appeared frequently in Attic vase-paintings and was exported with them. In the literary myths[71] Eos kidnapped Cephalus when he was hunting and took him to Syria. The second-century CE traveller Pausanias was informed that the abductor of Cephalus was Hemera, goddess of Day.[72] Although Cephalus was already married to Procris, Eos bore him three sons, including Phaeton and Hesperus, but he then began pining for Procris, causing a disgruntled Eos to return him to her — and put a curse on them. In Hyginus' report,[73] Cephalus accidentally killed Procris some time later after he mistook her for an animal while hunting; in Ovid's Metamorphoses vii, Procris, a jealous wife, was spying on him and heard him singing to the wind, but thought he was serenading his ex-lover Eos.

Eos pursues the reluctant Tithonos, who holds a lyre, on an Attic oinochoe of the Achilles Painter, ca. 470 BC–460 BCE (Louvre)

- In Greek mythology, Tithonus or Tithonos (Τιθωνός) was the lover of Eos, Titan[74] of the dawn, who was known in Roman mythology as Aurora. Tithonus was a Trojan by birth, the son of King Laomedon of Troy by a water nymph named Strymo (Στρυμώ). The mythology reflected by the fifth-century vase-painters of Athens envisaged Tithonus as a rhapsode, as the lyre in his hand, on an oinochoe of the Achilles Painter, ca. 470 BC–460 BCE (illustration) attests. Competitive singing, as in the Contest of Homer and Hesiod, is also depicted vividly in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo and mentioned in the two Hymns to Aphrodite.[75]

- Eos kidnapped Ganymede and Tithonus, both from the royal house of Troy, to be her lovers.[76] The mytheme of the goddess's mortal lover is an archaic one; when a role for Zeus was inserted, a bitter new twist appeared:[77] according to the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, when Eos asked Zeus to make Tithonus immortal,[78] she forgot to ask for eternal youth (218-38). Tithonus indeed lived forever

- "but when loathsome old age pressed full upon him, and he could not move nor lift his limbs, this seemed to her in her heart the best counsel: she laid him in a room and put to the shining doors. There he babbles endlessly, and no more has strength at all, such as once he had in his supple limbs." (Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite)

- In later tellings he eventually turned into a cicada, eternally living, but begging for death to overcome him.[79] In the Olympian system, the "queenly" and "golden-throned" Eos can no longer grant immortality to her lover as Selene had done, but must ask it of Zeus, as a boon.

- Eos bore Tithonus two sons, Memnon and Emathion. In the Epic Cycle that revolved around the Trojan War, Tithonus, who has travelled east from Troy into Assyria and founded Susa, is bribed to send his son Memnon to fight at Troy with a golden grapevine.[80] Memnon was called "King of the East" by Hesiod, but he was killed on the plain of Troy by Achilles. Aeschylus says in passing that Tithonus also had a mortal wife, named Cissia (otherwise unknown).

The so-called "Memnon pietà": The goddess Eos lifts up the body of her son Memnon (Attic red-figure cup, ca. 490–480 BC, from Capua, Italy) - In Greek mythology, Memnon (Greek: Mέμνων) was an Ethiopian king and son of Tithonus and Eos. As a warrior he was considered to be almost Achilles' equal in skill. During the Trojan War, he brought an army to Troy's defense. The death of Memnon echoes that of Hector, another defender of Troy whom Achilles also killed out of revenge for a fallen comrade, Patroclus. After Memnon's death, Zeus was moved by Eos' tears and granted him immortality. Memnon's death is related at length in the lost epic Aethiopis, composed after The Iliad circa the 7th century BC. Quintus of Smyrna records Memnon's death in Posthomerica. His death is also described in Philostratus' Imagines.

- In Greek mythology, the name Emathion (Ἠμαθίων) refers to four individuals.

- Ethiopian king

- Emathion was king of Aethiopia, the son of Tithonus and Eos, and brother of Memnon. Heracles killed him.

- Samothracian

- Emathion was king of Samothrace, was the son of Zeus and Electra (one of the Pleiades), brother to Dardanus, Iasion, Eetion, and (rarely) Harmonia. He sent soldiers to join Dionysus in his Indian campaigns.[83]

케팔로스와 에오스의 자녀: 파에톤 편집

And to Cephalus (케팔로스: 에오스의 연인) she (에오스) bare a splendid son,

- strong Phaethon (파에톤: 케팔로스와 에오스의 아들), a man like the gods, whom, when he was a young boy in the tender flower of glorious youth with childish thoughts, laughter-loving Aphrodite (아프로디테: 미와 사랑의 여신, 비너스) seized and caught up and made a keeper of her shrine by night, a divine spirit.

Cephalus and Eos, by Nicolas Poussin (circa 1630)

- Cephalus (Κέφαλος, Kephalos) is a name, used both for the hero-figure in Greek mythology and carried as a theophoric name by historical persons. The word kephalos is Greek for "head", perhaps used here because Cephalus was the founding "head" of a great family that includes Odysseus. It could be that Cephalus means the head of the sun who kills (evaporates) Procris (dew) with his unerring ray or 'javelin'. Cephalus was one of the lovers of the dawn goddess Eos.

이아손과 메테이아의 자녀: 메두스 편집

[993] And [Jason] the son of Aeson (이아손: 황금양모의 영웅, 아이손의 아들, 황금양모 원정대, 아르고나우타이) by the will of the gods led away from Aeetes (아이에테스: 헬리오스와 페르세이스의 아들, 콜키스의 왕), [Medea] the daughter of Aeetes (메데이아: 메데아, 메디아, 아이에테스와 아이디아의 딸, 마녀) the heaven-nurtured king, when he had finished the many grievous labours which the great king, over bearing Pelias (펠리아스: 이올코스의 왕, 이아손에게 황금양모를 찾아오게 보냄), that outrageous and presumptuous doer of violence, put upon him. But when the son of Aeson had finished them, he came to Iolcus (이올코스: 그리스 중부 테살리아에 있던 고대 도시) after long toil bringing the coy-eyed girl with him on his swift ship, and made her his buxom wife. And she was subject to Iason (이아손: 황금양모의 영웅, 아이손의 아들, 황금양모 원정대, 아르고나우타이), shepherd of the people, and bare

- a son Medeus (메두스: 이아손과 메데이아의 아들, 혹은 아이게우스와 메데이아의 아들) whom Cheiron (케이론 또는 키론: 켄타우로스, 현자, 수많은 영웅들의 스승) the son of Philyra (필리라: 오케아니드, 오케아노스와 테티스의 딸) brought up in the mountains. And the will of great Zeus was fulfilled.

- Iolcos (also known as Iolkos or Iolcus, Greek: Ιωλκός) is an ancient city, a modern village and a former municipality in Magnesia, Thessaly, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Volos, of which it is a municipal unit.[91] It is located in central Magnesia, north of the Pagasitic Gulf. Its land area is only 1.981 km². The municipal unit is divided into three communities with a total population of 2,071. Its Ágios Onoúfrios district has a land area of 0.200 km². The district has a population of 506 inhabitants.

- The municipal seat is the village of Áno Vólos (pop. 529). The small town of Anakasia (pop. 933) was the seat of the municipality of Iolkos. Anakasia has a school, a lyceum, a gymnasium, banks, a post office and a square (plateia). The only other villages are Ágios Onoúfrios (pop. 506), and Iolkós (103).

- Mythology

Pelias sends forth Jason, in an 1879 illustration from Stories from the Greek Tragedians by Alfred Church.

- According to ancient Greek mythology Aeson was the rightful king of Iolcos, but his half-brother Pelias usurped the throne. It was Pelias who sent Aeson's son Jason and his Argonauts to look for the Golden Fleece. The ship Argo set sail from Iolcos with a crew of fifty demigods and princes under Jason's leadership. Their mission was to reach Colchis in Aea at the eastern seaboard of the Black Sea and reclaim and bring back the Golden Fleece, a symbol of the opening of new trade routes. Along with the Golden Fleece Jason brought a wife, the sorceress Medea, king Aeetes' daughter, granddaughter of the Sun, niece of Circe, princess of Aea, and later queen of Iolcos, Corinth and Aea, and also murderer of her brother Absyrtus and her two sons from Jason, a tragic figure whose trials and tribulations were artfully dramatized in the much staged play by Euripides, Medea.

- Jason (Ἰάσων, Iásōn) was an ancient Greek mythological hero who was famous for his role as the leader of the Argonauts and their quest for the Golden Fleece. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea.

- Jason appeared in various literature in the classical world of Greece and Rome, including the epic poem Argonautica and the tragedy Medea. In the modern world, Jason has emerged as a character in various adaptations of his myths, such as the 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts and the 2000 TV miniseries of the same name.

- Jason has connections outside of the classical world, as he is seen as being the mythical founder of the city of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.

- Early years

- Family

- Jason's father is invariably Aeson, but there is great variation as to his mother's name. According to various authors, she could be:

- Jason was also said to have had a younger brother Promachus[100] and a sister Hippolyte, who married Acastus[102] (see Astydameia).

- Prosecution by Pelias

- Pelias (Aeson's half-brother) was very power-hungry, and he wished to gain dominion over all of Thessaly. Pelias was the product of a union between their shared mother, Tyro ("high born Tyro") the daughter of Salmoneus, and allegedly the sea god Poseidon. In a bitter feud, he overthrew Aeson (the rightful king), killing all the descendants of Aeson that he could. He spared his half-brother for unknown reasons. Alcimede I (wife of Aeson) already had an infant son named Jason whom she saved from being killed by Pelias, by having women cluster around the newborn and cry as if he were still-born. Alcimede sent her son to the centaur Chiron for education, for fear that Pelias would kill him — she claimed that she had been having an affair with him all along. Pelias, still fearful that he would one day be overthrown, consulted an oracle which warned him to beware of a man with one sandal.

- Many years later, Pelias was holding games in honor of the sea god and his alleged father, Poseidon, when Jason arrived in Iolcus and lost one of his sandals in the river Anauros ("wintry Anauros"), while helping an old woman to cross (the Goddess Hera in disguise). She blessed him for she knew, as goddesses do, what Pelias had up his sleeve. When Jason entered Iolcus (modern-day city of Volos), he was announced as a man wearing one sandal. Jason, knowing that he was the rightful king, told Pelias that and Pelias said, "To take my throne, which you shall, you must go on a quest to find the Golden Fleece." Jason happily accepted the quest.

- The Quest for the Golden Fleece

Jason bringing Pelias the Golden Fleece, Apulian red-figure calyx krater, ca. 340 BC–330 BC, Louvre

- Jason assembled a great group of heroes, known as the Argonauts after their ship, the Argo. The group of heroes included the Boreads (sons of Boreas, the North Wind) who could fly, Heracles, Philoctetes, Peleus, Telamon, Orpheus, Castor and Pollux, Atalanta, and Euphemus.

- The Isle of Lemnos

- The isle of Lemnos is situated off the Western coast of Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). The island was inhabited by a race of women who had killed their husbands. The women had neglected their worship of Aphrodite, and as a punishment the goddess made the women so foul in stench that their husbands could not bear to be near them. The men then took concubines from the Thracian mainland opposite, and the spurned women, angry at Aphrodite, killed all the male inhabitants while they slept. The king, Thoas, was saved by Hypsipyle, his daughter, who put him out to sea sealed in a chest from which he was later rescued. The women of Lemnos lived for a while without men, with Hypsipyle as their queen.

- During the visit of the Argonauts the women mingled with the men creating a new "race" called Minyae. Jason fathered twins with the queen. Heracles pressured them to leave as he was disgusted by the antics of the Argonauts. He had not taken part, which is truly unusual considering the numerous affairs he had with other women. [note 1]

- Cyzicus

- After Lemnos the Argonauts landed among the Doliones, whose king Cyzicus treated them graciously. He told them about the land beyond Bear Mountain, but forgot to mention what lived there. What lived in the land beyond Bear Mountain were the Gegeines which are a tribe of Earthborn giants with six arms and wore leather loincloths. While most of the crew went into the forest to search for supplies, the Gegeines saw that a few Argonauts were guarding the ship and raided it. Heracles was among those guarding the ship at the time and managed to kill most them until Jason and the others returned. Once some of the other Gegeines were killed, Jason and the Argonauts set sail.

- Sometime after their fight with the Gegeines, they sent some men to find food and water. Among these men was Heracles' servant Hylas who was gathering water while Heracles was out finding some wood to carve a new oar to replace the one that broke. The nymphs of the stream where Hylas was collecting were attracted to his good looks, and pulled him into the stream. Heracles returned to his Labors, but Hylas was lost forever. Others say that Heracles went to Colchis with the Argonauts, got the Golden Girdle of the Amazons and slew the Stymphalian Birds at that time.[출처 필요]

- The Argonauts departed, losing their bearings and landing again at the same spot that night. In the darkness, the Doliones took them for enemies and they started fighting each other. The Argonauts killed many of the Doliones, among them the king Cyzicus. Cyzicus' wife killed herself. The Argonauts realized their horrible mistake when dawn came and held a funeral for him.

- Phineas and the Harpies

- Soon Jason reached the court of Phineus of Salmydessus in Thrace. Zeus had sent the Harpies to steal the food put out for Phineas each day. Jason took pity on the emaciated king and killed the Harpies when they returned; in other versions, Calais and Zetes chase the Harpies away. In return for this favor, Phineas revealed to Jason the location of Colchis and how to pass the Symplegades, or The Clashing Rocks, and then they parted.

- The Symplegades

- The only way to reach Colchis was to sail through the Symplegades (Clashing Rocks), huge rock cliffs that came together and crushed anything that traveled between them. Phineas told Jason to release a dove when they approached these islands, and if the dove made it through, to row with all their might. If the dove was crushed, he was doomed to fail. Jason released the dove as advised, which made it through, losing only a few tail feathers. Seeing this, they rowed strongly and made it through with minor damage at the extreme stern of the ship. From that time on, the clashing rocks were forever joined leaving free passage for others to pass.

- The arrival in Colchis

Jason and the Snake - Jason arrived in Colchis (modern Black Sea coast of Georgia) to claim the fleece as his own. It was owned by King Aeetes of Colchis. The fleece was given to him by Phrixus. Aeetes promised to give it to Jason only if he could perform three certain tasks. Presented with the tasks, Jason became discouraged and fell into depression. However, Hera had persuaded Aphrodite to convince her son Eros to make Aeetes's daughter, Medea, fall in love with Jason. As a result, Medea aided Jason in his tasks. First, Jason had to plow a field with fire-breathing oxen, the Khalkotauroi, that he had to yoke himself. Medea provided an ointment that protected him from the oxen's flames. Then, Jason sowed the teeth of a dragon into a field. The teeth sprouted into an army of warriors (spartoi). Medea had previously warned Jason of this and told him how to defeat this foe. Before they attacked him, he threw a rock into the crowd. Unable to discover where the rock had come from, the soldiers attacked and defeated one another. His last task was to overcome the sleepless dragon which guarded the Golden Fleece. Jason sprayed the dragon with a potion, given by Medea, distilled from herbs. The dragon fell asleep, and Jason was able to seize the Golden Fleece. He then sailed away with Medea. Medea distracted her father, who chased them as they fled, by killing her brother Apsyrtus and throwing pieces of his body into the sea; Aeetes stopped to gather them. In another version, Medea lured Apsyrtus into a trap. Jason killed him, chopped off his fingers and toes, and buried the corpse. In any case, Jason and Medea escaped.

- The return journey

- On the way back to Iolcus, Medea prophesied to Euphemus, the Argo's helmsman, that one day he would rule Cyrene. This came true through Battus, a descendant of Euphemus. Zeus, as punishment for the slaughter of Medea's own brother, sent a series of storms at the Argo and blew it off course. The Argo then spoke and said that they should seek purification with Circe, a nymph living on the island of Aeaea. After being cleansed, they continued their journey home.

- Sirens

- Chiron had told Jason that without the aid of Orpheus, the Argonauts would never be able to pass the Sirens — the same Sirens encountered by Odysseus in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. The Sirens lived on three small, rocky islands called Sirenum scopuli and sang beautiful songs that enticed sailors to come to them, which resulted in the crashing of their ship into the islands. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew his lyre and played music that was more beautiful and louder, drowning out the Sirens' bewitching songs.

- Talos

- The Argo then came to the island of Crete, guarded by the bronze man, Talos. As the ship approached, Talos hurled huge stones at the ship, keeping it at bay. Talos had one blood vessel which went from his neck to his ankle, bound shut by only one bronze nail (as in metal casting by the lost wax method). Medea cast a spell on Talos to calm him; she removed the bronze nail and Talos bled to death. The Argo was then able to sail on.

- Jason returns

- Medea, using her sorcery, claimed to Pelias' daughters that she could make their father younger by chopping him up into pieces and boiling the pieces in a cauldron of water and magical herbs. She demonstrated this remarkable feat with a sheep, which leapt out of the cauldron as a lamb. The girls, rather naively, sliced and diced their father and put him in the cauldron. Medea did not add the magical herbs, and Pelias was dead.

- It should be noted that Thomas Bulfinch has an antecedent to the interaction of Medea and the daughters of Pelias. Jason, celebrating his return with the Golden Fleece, noted that his father was too aged and infirm to participate in the celebrations. He had seen and been served by Medea's magical powers. He asked Medea to take some years from his life and add them to the life of his father. She did so, but at no such cost to Jason's life. Pelias' daughters saw this and wanted the same service for their father. Pelias' son, Acastus, drove Jason and Medea into exile for the murder, and the couple settled in Corinth.

- Treachery of Jason

- In Corinth, Jason became engaged to marry Creusa (sometimes referred to as Glauce), a daughter of the King of Corinth, to strengthen his political ties. When Medea confronted Jason about the engagement and cited all the help she had given him, he retorted that it was not she that he should thank, but Aphrodite who made Medea fall in love with him. Infuriated with Jason for breaking his vow that he would be hers forever, Medea took her revenge by presenting to Creusa a cursed dress, as a wedding gift, that stuck to her body and burned her to death as soon as she put it on. Creusa's father, Creon, burned to death with his daughter as he tried to save her. Then Medea killed the two boys that she bore to Jason, fearing that they would be murdered or enslaved as a result of their mother's actions. When Jason came to know of this, Medea was already gone; she fled to Athens in a chariot sent by her grandfather, the sun-god Helios.

- Later Jason and Peleus, father of the hero Achilles, attacked and defeated Acastus, reclaiming the throne of Iolcus for himself once more. Jason's son, Thessalus, then became king.

- As a result of breaking his vow to love Medea forever, Jason lost his favor with Hera and died lonely and unhappy. He was asleep under the stern of the rotting Argo when it fell on him, killing him instantly.

- In literature

Jason with the Golden Fleece, Bertel Thorvaldsen's first masterpiece. - Though some of the episodes of Jason's story draw on ancient material, the definitive telling, on which this account relies, is that of Apollonius of Rhodes in his epic poem Argonautica, written in Alexandria in the late 3rd century BC.

- Another Argonautica was written by Gaius Valerius Flaccus in the late 1st century AD, eight books in length. The poem ends abruptly with the request of Medea to accompany Jason on his homeward voyage. It is unclear if part of the epic poem has been lost, or if it was never finished. A third version is the Argonautica Orphica, which emphasizes the role of Orpheus in the story.

- Jason is briefly mentioned in Dante's Divine Comedy in the poem Inferno. He appears in the Canto XVIII. In it, he is seen by Dante and his guide Virgil being punished in Hell's Eighth Circle (Bolgia 1) by being driven to march through the circle for all eternity while being whipped by devils. He is included among the panderers and seducers (possibly for his seduction and subsequent abandoning of Medea).

- The story of Medea's revenge on Jason is told with devastating effect by Euripides in his tragedy Medea.

- The mythical geography of the voyage of the Argonauts has been connected to specific geographic locations by Livio Stecchini[103] but his theories have not been widely adopted.

- Popular culture

- Jason appeared in the Hercules episode "Hercules and the Argonauts" voiced by William Shatner. He is shown to have been a student of Philoctetes and takes his advice to let Hercules travel with him.

- In The Heroes of Olympus story "The Lost Hero," there was a reference to the mythical Jason when Jason Grace and his friends encounter Medea.

Medea rejuvenates Aeson by Nicolas-André Monsiau.

- In Greek mythology, Aeson or Aison (Αἴσων) was the son of Cretheus and Tyro, who also had his brothers Pheres and Amythaon. Aeson was the father of Jason and Promachus with Polymele, the daughter of Autolycus.[104] Other sources say the mother of his children was Alcimede[105] or Amphinome.[106] Aeson's mother Tyro had two other sons, Neleus and Pelias, with the god of the sea Poseidon.[107]

- Pelias was power-hungry and he wished to gain dominion over all of Thessaly. To this end, he banished Neleus and Pheres and locked Aeson in the dungeons in Iolcus. Aeson sent Jason to Chiron to be educated while Pelias, afraid that he would be overthrown, was warned by an oracle to beware a man wearing one sandal.

- Many years later, Pelias was holding the Olympics in honor of Poseidon when Jason, rushing to Iolcus, lost one of his sandals in a river while helping Hera (Juno), in the form of an old woman, cross. When Jason entered Iolcus, he was announced as a man wearing one sandal. Paranoid, Pelias asked him what he (Jason) would do if confronted with the man who would be his downfall. Jason responded that he would send that man after the Golden Fleece. Pelias took that advice and sent Jason to retrieve the Golden Fleece.

- During Jason's absence, Pelias intended to kill Aeson. However, Aeson committed suicide by drinking bull's blood. His wife killed herself as well, and Pelias murdered their infant son Promachus.[108]

- Alternatively, he survived until Jason and his new wife, Medea, came back to Iolcus. She slit Aeson's throat, then put his corpse in a pot and Aeson came to life as a young man. She then told Pelias' daughters she would do the same for their father. They slit his throat and Medea refused to raise him, so Pelias stayed dead.[109]

Pelias sends forth Jason, in an 1879 illustration from Stories from the Greek Tragedians by Alfred Church.

- Pelias (Ancient Greek: Πελίας) was king of Iolcus in Greek mythology, the son of Tyro and Poseidon. His wife is recorded as either Anaxibia, daughter of Bias, or Phylomache, daughter of Amphion. He was the father of Acastus, Pisidice, Alcestis, Pelopia, Hippothoe, Amphinome, Evadne, Asteropeia, and Antinoe.[110]

- Tyro was married to Cretheus (with whom she had three sons, Aeson, Pherês, and Amythaon) but loved Enipeus, a river god. She pursued Enipeus, who refused her advances. One day, Poseidon, filled with lust for Tyro, disguised himself as Enipeus and from their union was born Pelias and Neleus, twin boys. Tyro exposed her sons on a mountain to die, but they were found by a herdsman who raised them as his own, as one story goes, or they were raised by a maid. When they reached adulthood, Pelias and Neleus found Tyro and killed their stepmother, Sidero, for having mistreated her. Sidero hid in a temple to Hera but Pelias killed her anyway, causing Hera's undying hatred of Pelias. Pelias was power-hungry and he wished to gain dominion over all of Thessaly. To this end, he banished Neleus and Pherês, and locked Aeson in the dungeons in Iolcus (by the modern city of Volos). While in the dungeons, Aeson married and had several children, most famously, Jason. Aeson sent Jason away from Iolcus in fear that Pelias would kill him as an heir to the throne. Jason grew in the care of Chiron the centaur, on Mount Pelium, to be educated while Pelias, paranoid that he would be overthrown, was warned by an oracle to beware a man wearing one sandal.[111]

- Many years later, Pelias was holding the Olympics and offered a sacrifice by the sea in honor of Poseidon. Jason, who was summoned with many others to take part in the sacrifice, lost one of his sandals in the flooded river Anaurus while rushing to Iolcus. In Virgil's Aeneid, Hera had disguised herself as an old woman, whom Jason was helping across the river when he lost his sandal. When Jason entered Iolcus, he was announced as a man wearing one sandal. Paranoid, Pelias asked Jason what he would do if confronted with the man who would be his downfall. Jason responded that he would send that man after the Golden Fleece. Pelias took Jason's advice and sent him to retrieve the Golden Fleece. It would be found at Colchis, in a grove sacred to Ares, the god of war. Though the Golden Fleece simply hung on an oak tree, this was a seemingly impossible task, as an ever-watchful dragon guarded it.[112]

- Jason made preparations by commanding the shipwright Argus to build a ship large enough for fifty men, which he would eventually call the Argo. These heroes who would join his quest were known as the Argonauts. Upon their arrival Jason requested the Golden Fleece from the King of Colchis, Aeëtes. Aeëtes demanded that Jason must first yoke a pair of fire-breathing bulls to a plough and sew the dragon’s mouth shut. Medea, daughter of Aeëtes, fell in love with Jason, and being endowed with magical powers, aided him in his completion of the difficult task. She cast a spell to put the dragon to sleep, enabling Jason to obtain the Golden Fleece from the oak tree. Jason, Medea, and the Argonauts fled Colchis and began their return journey to Thessaly.[113]

- During Jason's absence, Pelias thought the Argo had sunk, and this was what he told Aeson and Promachus, who committed suicide by drinking poison. However, it is unknown but possible that the two were both killed directly by Pelias. When Jason and Medea returned, Pelias still refused to give up his throne. Medea conspired to have Pelias' own daughters (Peliades) kill him. She told them she could turn an old ram into a young ram by cutting up the old ram and boiling it. During the demonstration, a live, young ram jumped out of the pot. Excited, the girls cut their father into pieces and threw them in a pot, in the expectation that he would emerge rejuvenated. Pelias, of course, did not survive. As he was now an accessory to a terrible crime, Jason was still not made king. Pelias' son Acastus later drove Jason and Medea to Corinth and so reclaimed the kingdom. An alternate telling of the story has Medea slitting the throat of Jason's father Aeson, who she then really does revive as a much younger man; Pelias' daughters then slit their father's throat after she promises to do the same for him, and she merely breaks her word and leaves him dead.

- In Greek mythology, Medus was the son of Medea. His father is generally agreed to be Aegeas, although Hesiod states that Jason fathered him and Cheiron raised him. Medus was driven from Athens to Colchis with his mother. Medea's father Aeetes was the former king of Colchis, and Aeetes's brother Perses ruled after his death; by some accounts Aeetes was murdered by Perses. Perses imprisoned Medus to protect his throne from any potential claimants. To free him, Medea impersonated a priestess and demanded he be given to her for sacrifice to appease the gods, as a plague was at the time being visited upon Colchis. Perses agreed, and was subsequently killed by the sacrificial blade in the hands of either Medus or his mother. Medus thus came to rule, and when he conquered a neighboring land it was named Media in honor of either Medus or Medea.

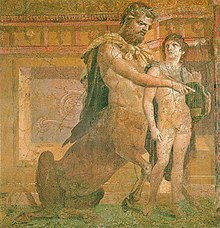

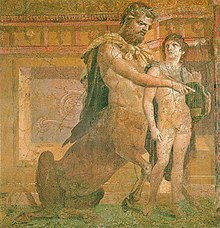

Chiron and Achilles in a fresco from Herculaneum (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples).

- In Greek mythology, Chiron /ˈkaɪrən/ (also Cheiron or Kheiron; Χείρων "hand"[114]) was held to be the superlative centaur among his brethren.

- History

- Like the satyrs, centaurs were notorious for being wild and lusty, overly indulgent drinkers and carousers, given to violence when intoxicated, and generally uncultured delinquents. Chiron, by contrast, was intelligent, civilized and kind, but he was not related directly to the other centaurs.[115] He was known for his knowledge and skill with medicine. According to an archaic myth[116] he was sired by Cronus when he had taken the form of a horse[117] and impregnated the nymph Philyra.[118] Chiron's lineage was different from other centaurs, who were born of sun and raincloud, rendered by Greeks of the Classic period as from the union of the king Ixion, consigned to a fiery wheel, and Nephele ("cloud"), which in the Olympian telling Zeus invented to look like Hera. Myths in the Olympian tradition attributed Chiron's uniquely peaceful character and intelligence to teaching by Apollo and Artemis in his younger days.

Amphora suggested to be Achilles riding Chiron. British Museum ref 틀:British-Museum-db.

- Chiron frequented Mount Pelion; there he married the nymph Chariclo who bore him three daughters, Hippe (also known as Melanippe (also the name of her daughter), the "Black Mare" or Euippe, "truly a mare"), Endeis, and Ocyrhoe, and one son Carystus.

- A great healer, astrologer, and respected oracle, Chiron was said to be the first among centaurs and highly revered as a teacher and tutor. Among his pupils were many culture heroes: Asclepius, Aristaeus, Ajax, Aeneas, Actaeon, Caeneus, Theseus, Achilles, Jason, Peleus, Telamon, Perseus, sometimes Heracles, Oileus, Phoenix, and in one Byzantine tradition, even Dionysus: according to Ptolemaeus Chennus of Alexandria, "Dionysius was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations."[119]

- Death

A lekythos depicting Chiron and Achilles

- His nobility is further reflected in the story of his death, as Prometheus sacrificed his life, allowing mankind to obtain the use of fire. Being the son of Cronus, a Titan, he was immortal and so could not die. So it was left to Heracles to arrange a bargain with Zeus to exchange Chiron's immortality for the life of Prometheus, who had been chained to a rock and left to die for his transgressions.[120] Chiron had been poisoned with an arrow belonging to Heracles that had been treated with the blood of the Hydra, or, in other versions, poison that Chiron had given to the hero when he had been under the honorable centaur’s tutelage. According to a Scholium on Theocritus,[121] this had taken place during the visit of Heracles to the cave of Pholus on Mount Pelion in Thessaly when he visited his friend during his fourth labour in defeating the Erymanthian Boar. While they were at supper, Heracles asked for some wine to accompany his meal. Pholus, who ate his food raw, was taken aback. He had been given a vessel of sacred wine by Dionysus sometime earlier, to be kept in trust for the rest of the centaurs until the right time for its opening. At Heracles' prompting, Pholus was forced to produce the vessel of sacred wine. The hero, gasping for wine, grabbed it from him and forced it open. Thereupon the vapours of the sacred wine wafted out of the cave and intoxicated the wild centaurs, led by Nessus, who had gathered outside. They attacked the cave with stones and fir trees. Heracles was forced to shoot many arrows (poisoned with the blood of the Hydra) to drive them back. During this assault, Chiron was hit in the thigh by one of the poisoned arrows. After the centaurs had fled, Pholus emerged from the cave to observe the destruction. Being of a philosophical frame of mind, he pulled one of the arrows from the body of a dead centaur and wondered how such a little thing as an arrow could have caused so much death and destruction. In that instant, he let slip the arrow from his hand and it dropped and hit him in the hoof, killing him instantly. This, however, is open to controversy, because Pholus shared the "civilized centaur" form with Chiron in some art images, and thus would have been immortal.

- Ironically, Chiron, the master of the healing arts, could not heal himself, so he willingly gave up his immortality. He was honoured with a place in the sky, identified by the Greeks as the constellation Centaurus.

- Chiron saved the life of Peleus when Acastus tried to kill him by taking his sword and leaving him out in the woods to be slaughtered by the centaurs. Chiron retrieved the sword for Peleus. Some sources speculate that Chiron was originally a Thessalian god, later subsumed into the Greek pantheon as a centaur.[출처 필요]

- Ovid relates[122] another version of Chiron's death. In this version both Chiron and his student (see below) Achilles are in the cave on Mt. Pelion with Hercules. When Chiron admires the weapons of the mighty hero, Achilles is tempted to touch them making one of the arrows fall and strike the left foot of the Centaur. Achilles cries, as he would for his father, as Chiron leaves for the skies.

- Students

The Education of Achilles, by Eugène Delacroix. - Among the students of Chiron are:

- Actaeon - Actaeon, who was bred by Chiron to be a hunter, is famous for his terrible death for he in the shape of a deer was devoured by his own dogs. The dogs, ignorant of what they had done, came to the cave of Chiron seeking their master, and the Centaur fashioned an image of Actaeon in order to soothe their grief.

- Peleus - Peleus, father of Achilles, was once rescued by Chiron: Acastus, son of Pelias, purified Peleus for having killed (undesignedly) his father-in-law Eurytion. However, Acastus' wife, Astydameia, fell in love with Peleus, and as he refused her she intrigued against him, telling Acastus that Peleus had attempted to rape her. Acastus would not kill the man he had purified, but took him to hunt on Mount Pelion. When Peleus had fallen asleep, Acastus deserted him, hiding his sword. On arising and looking for his sword, Peleus was caught by the centaurs and would have perished, if he had not been saved by Chiron, who also restored him his sword after having sought and found it. Chiron arranged the marriage of Peleus with Thetis,[126] bringing Achilles up for her. He also told Peleus how to conquer the Nereid Thetis who, changing her form, could prevent him from catching her. In other legends, it was Proteus who helped Peleus. When Peleus married Thetis, he received from Chiron an ashen spear, which Achilles took to the war at Troy. This spear is the same with which Achilles healed Telephus by scraping off the rust.

- The Precepts of Chiron

The Education of Achilles by Donato Creti, 1714 (Musei Civici d'Arte Antica, Bologna)

- A didactic poem, Precepts of Chiron, part of the traditional education of Achilles, was considered to be among Hesiod's works by some of the later Greeks, for example, the Romanized Greek traveller of the 2nd century CE, Pausanias,[127] who noted a list of Hesiod's works that were shown to him, engraved on an ancient and worn leaden tablet, by the tenders of the shrine at Helicon in Boeotia. But another, quite different tradition was upheld of Hesiod's works, Pausanias notes, which included the Precepts of Chiron. Apparently it was among works from Acharnae written in heroic hexameters and attached to the famous name of Hesiod, for Pausanias adds "Those who hold this view also say that Hesiod was taught soothsaying by the Acharnians." Though it has been lost, fragments in heroic hexameters that survive in quotations are considered to belong to it.[128] The common thread in the fragments, which may reflect in some degree the Acharnian image of Chiron and his teaching, is that it is expository rather than narrative, and suggests that, rather than recounting the inspiring events of archaic times as men like Nestor[129] or Glaucus[130] might do, Chiron taught the primeval ways of mankind, the gods and nature, beginning with the caution "First, whenever you come to your house, offer good sacrifices to the eternal gods". Chiron in the Precepts considered that no child should have a literary education until he had reached the age of seven.[131] A fragment associated with the Precepts concerns the span of life of the nymphs, in the form of an ancient number puzzle:

A chattering crow lives out nine generations of aged men, but a stag's life is four times a crow's, and a raven's life makes three stags old, while the phoenix outlives nine ravens, but we, the rich-haired Nymphs, daughters of Zeus the aegis-holder, outlive ten phoenixes."[132]

- In human terms, Chiron advises, "Decide no suit, until you have heard both sides speak".

- The Alexandrian critic Aristophanes of Byzantium (late 3rd-early 2nd century BCE) was the first to deny that the Precepts of Chiron was the work of Hesiod.[133]

- Philyra (Greek Φιλύρα "linden-tree") is the name of three distinct characters in Greek mythology.

- Oceanid

- Philyra was an Oceanid, a daughter of Oceanus and Tethys, the second oldest Oceanid according to Callimachus.[134] Chiron was her son by Cronus,[135][136] who chased her and consorted with her in the shape of a stallion, hence the half-human, half-equine shape of their offspring;[137][138] this was said to have taken place on Mount Pelion.[139] When she gave birth to her son, she was so disgusted by how he looked that she abandoned him at birth, and implored the gods to transform her into anything other than anthrpomorphic as she could not bear the shame of having had such a monstrous child; the gods changed her into a linden tree.[140][141] Yet in some versions Philyra and Chariclo, the wife of Chiron, nursed the young Achilles;[142][143] Chiron's dwelling on Pelion where his disciples were reared was known as "Philyra's cave".[144][145][146] Chiron was often referred to by the matronymic Philyrides or the like.[147][148][149][150][151]

- Two other sons of Cronos and Philyra may have been Dolops[152] and Aphrus, the ancestor and eponym of the Aphroi, i. e. the native Africans.[153]

아이아코스와 프사마테의 자녀: 포코스 편집

[1003] But of the daughters of Nereus (네레우스: 바다의 노인, 물과 바다의 남신, 폰토스와 가이아의 아들), the Old man of the Sea, Psamathe (프사메테, 네레이드, 모래여인) the fair goddess, was loved by Aeacus (아이아코스: 섬 나라 아이기나의 전설적인 왕, 제우스와 님프 이이기나의 아들, 미노스· 라다만티스와 함께 하데스의 재판관) through golden Aphrodite and bare

- Psamathe (Greek: Ψάμαθη, from ψάμαθος "sand of the sea-shore") was a Nereid in Greek mythology, i.e., one of the fifty daughters of Nereus and Doris. The goddess of sand beaches, Psamathe was the wife of Proteus[157] and the mother of Phocus by Aeacus.[158]

- This was also the name of the mortal mother of Linus by Apollo. This second Psamathe was the daughter of Crotopus, king of Argos, who, fearing her father, gave her infant son Linus to shepherds to be raised; after reaching adulthood, he was torn apart by the shepherd's dogs, and Psamathe was killed by her father, who would not believe that she had had intercourse with a god rather than a mortal. Apollo avenged her murder by sending a child-killing plague to Argos, which would not cease until the Argives, at the god's command, paid honors to Psamathe and Linus.[159] In an alternate version, the baby Linus was torn apart by the king's sheepdogs upon being exposed and Apollo sent Poene, the personification of punishment, upon the city. Poene would steal children from their mothers until Coroebus killed her.[160]

- Some translations of Ovid have the name as Psamanthe.[161]

| Greek underworld | |

|---|---|

| Residents | |

| Geography | |

| Famous inmates | |

| Visitors | |

- Aeacus (also spelled Eacus, Αἰακός) was a mythological king of the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf.

- He was son of Zeus and Aegina, a daughter of the river-god Asopus.[162] He was born on the island of Oenone or Oenopia, to which Aegina had been carried by Zeus to secure her from the anger of her parents, and whence this island was afterwards called Aegina.[163][164][165][166][167] According to some accounts Aeacus was a son of Zeus and Europa. Some traditions related that at the time when Aeacus was born, Aegina was not yet inhabited, and that Zeus changed the ants (μύρμηκες) of the island into men (Myrmidons) over whom Aeacus ruled, or that he made men grow up out of the earth.[163][168][169] Ovid, on the other hand, supposes that the island was not uninhabited at the time of the birth of Aeacus, and states that, in the reign of Aeacus, Hera, jealous of Aegina, ravaged the island bearing the name of the latter by sending a plague or a fearful dragon into it, by which nearly all its inhabitants were carried off, and that Zeus restored the population by changing the ants into men.[170][171][172]

Aeacus and Telamon by Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune.

- These legends seem to be a mythical account of the colonization of Aegina, which seems to have been originally inhabited by Pelasgians, and afterwards received colonists from Phthiotis, the seat of the Myrmidons, and from Phlius on the Asopus. Aeacus while he reigned in Aegina was renowned in all Greece for his justice and piety, and was frequently called upon to settle disputes not only among men, but even among the gods themselves.[173][174] He was such a favourite with the latter, that, when Greece was visited by a drought in consequence of a murder which had been committed, the oracle of Delphi declared that the calamity would not cease unless Aeacus prayed to the gods that it might.[163][175] Aeacus prayed, and it ceased in consequence. Aeacus himself showed his gratitude by erecting a temple to Zeus Panhellenius on mount Panhellenion,[176] and the Aeginetans afterwards built a sanctuary in their island called Aeaceum, which was a square place enclosed by walls of white marble. Aeacus was believed in later times to be buried under the altar in this sacred enclosure.[177]

- A legend preserved in Pindar relates that Apollo and Poseidon took Aeacus as their assistant in building the walls of Troy.[178] When the work was completed, three dragons rushed against the wall, and while the two of them which attacked those parts of the wall built by the gods fell down dead, the third forced its way into the city through the part built by Aeacus. Hereupon Apollo prophesied that Troy would fall through the hands of Aeacus's descendants, the Aeacidae.

- Aeacus was also believed by the Aeginetans to have surrounded their island with high cliffs to protect it against pirates.[179] Several other incidents connected with the story of Aeacus are mentioned by Ovid.[180] By Endeïs Aeacus had two sons, Telamon (father of Ajax and Teucer) and Peleus (father of Achilles), and by Psamathe a son, Phocus, whom he preferred to the two others, both of whom contrived to kill Phocus during a contest, and then fled from their native island.

- After his death, Aeacus became (along with the Cretan brothers Rhadamanthus and Minos) one of the three judges in Hades,[181][182] and according to Plato especially for the shades of Europeans.[183][184] In works of art he was represented bearing a sceptre and the keys of Hades.[163][185] Aeacus had sanctuaries both at Athens and in Aegina,[177][186][187] and the Aeginetans regarded him as the tutelary deity of their island.[188]

- In The Frogs (405 BC) by Aristophanes, Dionysus descends to Hades and announces himself as Heracles. Aeacus laments Heracles's theft of Cerberus and sentences Dionysus to Acheron and torment by hounds of Cocytus, Echidna, the Tartesian eel, and Tithrasian Gorgons.

- Alexander the Great traced his ancestry (through his mother) to Aeacus.

- In Greek mythology, Phocus (Φῶκος) was the name of the eponymous hero of Phocis.[189] Ancient sources relate of more than one figure of this name, and of these at least two are explicitly said to have had Phocis named after them. A scholiast on the Iliad distinguishes between two possible eponyms: Phocus the son of Aeacus and Psamathe, and Phocus the son of Poseidon and Pronoe.[190]

- Phocus, son of Aeacus

- Phocus of Aegina was the son of Aeacus and Psamathe. His mother, the Nereid goddess of sand beaches, transformed herself into a seal when she was ambushed by Aeacus, and was raped as a seal; conceived in the rape, Phocus' name means "seal".[88] According to Pindar, Psamathe gave birth to Phocus on the seashore.[191] By Asteria or Asterodia, Phocus had twin sons, Crisus and Panopeus.[192]

- Aeacus favored Phocus over Peleus and Telamon, his two sons with Endeïs. The Bibliotheca characterizes Phocus as a strong athlete, whose athletic ability caused his half-brothers to grow jealous. Their jealousy drove them to murder him during sport practice; Telamon, the stronger half-brother, threw a discus at Phocus' head, killing him. The brothers hid the corpse in a thicket, but Aeacus discovered the body and punished Peleus and Telamon by exiling them from Aegina. Telamon was sent to Salamis, where he became king after Cychreus, the reigning king, died without an heir, while Peleus went to Phthia, where he was purified by the Phthian King Eurythion.[88]

- However, the tradition varies with regards to the nature of Phocus' death. Other myths use the following as a means to describe Phocus' death:

- Telamon threw a quoit at his head.

- Telamon killed him with a spear while hunting.[193]

- Peleus killed him with a stone during a contest in pentathlon to please Endeis, as Phocus was her husband's son by a different woman.[194]

- Some authors simply mention that Peleus and Telamon killed Phocus out of envy, without giving any details.[195]

- Other sources say that whichever brother was responsible, it was an accident.

- John Tzetzes relates that Psamathe sent a wolf to avenge her son's death, but when the wolf began to devour Peleus' kine, Thetis changed it into stone.[196]

- According to Pausanias, Phocus visited the region that was later called Phocis shortly before his death, with the intent of settling there and gaining rule over the local inhabitants. During his stay there, he became friends with Iaseus: Pausanias describes a painting of Phocus giving his seal ring to Iaseus as a sign of friendship; the author notes that Phocus is portrayed as a youth while Iaseus looks older and has a beard.[197] Elsewhere, Pausanias mentions that Phocus' sons Crisus and Panopaeus emigrated to Phocis.[198]

- The tomb of Phocus was shown at Aegina beside the shrine of Aeacus.[194]

펠레오스와 테티스의 자녀: 아킬레우스 편집

And the silver-shod goddess Thetis (테티스, 네레이드, 아킬레우스의 어머니) was subject to Peleus (펠레우스: 아이기나의 왕 아이아코스의 아들, 텔라몬과 형제, 텔라몬과 함께 헤라클레스의 친구, 테티스와 결혼, 아킬레우스의 아버지) and brought forth

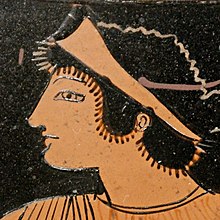

Head of Thetis from an Attic red-figure pelike, c. 510–500 BC - Louvre. -

- The following article is about the Greek lesser sea goddess of late myths. Thetis should not be confused with Themis, the embodiment of the laws of nature, but see the sea-goddess Tethys. For other uses, see Thetis (disambiguation).

- Silver-footed Thetis (Ancient Greek: Θέτις), disposer or "placer" (the one who places), is encountered in Greek mythology mostly as a sea nymph or known as the goddess of water, one of the fifty Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus. [199]

- When described as a Nereid in Classical myths, Thetis was the daughter of Nereus and Doris,[200] and a granddaughter of Tethys with whom she sometimes shares characteristics. Often she seems to lead the Nereids as they attend to her tasks. Sometimes she also is identified with Metis.

- Some sources argue that she was one of the earliest of deities worshipped in Archaic Greece, the oral traditions and records of which are lost. Only one written record, a fragment, exists attesting to her worship and an early Alcman hymn exists that identifies Thetis as the creator of the universe. Worship of Thetis as the goddess is documented to have persisted in some regions by historical writers such as Pausanias.

- In the Trojan War cycle of myth, the wedding of Thetis and the Greek hero Peleus is one of the precipitating events in the war, leading also to the birth of their child Achilles.

- Marriage to Peleus and the Trojan War

Thetis changing into a lioness as she is attacked by Peleus, Attic red-figured kylix by Douris, c. 490 BC from Vulci, Etruria - Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

- Zeus had received a prophecy that Thetis's son would become greater than his father, like Zeus had dethroned his father to lead the succeeding pantheon. In order to ensure a mortal father for her eventual offspring, Zeus and his brother Poseidon made arrangements for her to marry a human, Peleus, son of Aeacus, but she refused him.

- Proteus, an early sea-god, advised Peleus to find the sea nymph when she was asleep and bind her tightly to keep her from escaping by changing forms. She did shift shapes, becoming flame, water, a raging lioness, and a serpent.[201] Peleus held fast. Subdued, she then consented to marry him. Thetis is the mother of Achilles by Peleus, who became king of the Myrmidons.

- According to classical mythology, the wedding of Thetis and Peleus was celebrated on Mount Pelion, outside the cave of Chiron, and attended by the deities: there they celebrated the marriage with feasting. Apollo played the lyre and the Muses sang, Pindar claimed. At the wedding Chiron gave Peleus an ashen spear that had been polished by Athene and had a blade forged by Hephaestus. Poseidon gave him the immortal horses, Balius and Xanthus. Eris, the goddess of discord, had not been invited, however. In spite, she threw a golden apple into the midst of the goddesses that was to be awarded only "to the fairest." In most interpretations, the award was made during the Judgement of Paris and eventually occasioned the Trojan War.

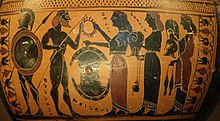

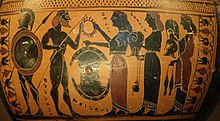

Thetis and attendants bring armor she had prepared for him to Achilles, an Attic black-figure hydria, c. 575–550 BC - Louvre. - In the later classical myths Thetis worked her magic on the baby Achilles by night, burning away his mortality in the hall fire and anointing the child with ambrosia during the day, Apollonius tells. When Peleus caught her searing the baby, he let out a cry.

- "Thetis heard him, and catching up the child threw him screaming to the ground, and she like a breath of wind passed swiftly from the hall as a dream and leapt into the sea, exceeding angry, and thereafter returned never again."

- In a variant of the myth, Thetis tried to make Achilles invulnerable by dipping him in the waters of the Styx (the river of Hades). However, the heel by which she held him was not touched by the Styx's waters, and failed to be protected. In the story of Achilles in the Trojan War in the Iliad, Homer does not mention this weakness of Achilles' heel. A similar myth of immortalizing a child in fire is connected to Demeter (compare the myth of Meleager). Some myths relate that because she had been interrupted by Peleus, Thetis had not made her son physically invulnerable. His heel, which she was about to burn away when her husband stopped her, had not been protected.

- Peleus gave the boy to Chiron to raise. Prophecy said that the son of Thetis would have either a long but dull life, or a glorious but brief life. When the Trojan War broke out, Thetis was anxious and concealed Achilles, disguised as a girl, at the court of Lycomedes. When Odysseus found that one of the girls at court was not a girl, but Achilles, he dressed as a merchant and set up a table of vanity items and jewellery and called to the group. Only Achilles picked up the golden sword that lay to one side, and Odysseus quickly revealed him to be male. Seeing that she could no longer prevent her son from realizing his destiny, Thetis then had Hephaestus make a shield and armor.

- When Achilles was killed by Paris, Thetis came from the sea with the Nereids to mourn him, and she collected his ashes in a golden urn, raised a monument to his memory, and instituted commemorative festivals.

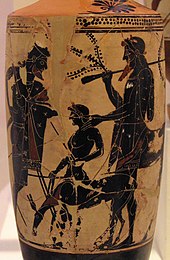

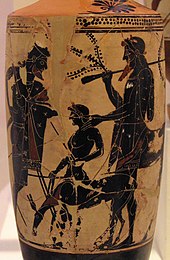

Peleus consigns Achilles to Chiron's care, white-ground lekythos by the Edinburgh Painter, ca. 500 BC, (National Archaeological Museum of Athens) - In Greek mythology, Peleus (/ˈpɛlˌjuːs/; Πηλεύς, Pēleus) was a hero whose myth was already known to the hearers of Homer in the late 8th century BC.[202] Peleus was the son of Aeacus, king of the island of Aegina,[203] and Endeïs, the oread of Mount Pelion in Thessaly;[204] he was the father of Achilles. He and his brother Telamon were friends of Heracles, serving in his expedition against the Amazons, his war against King Laomedon, and with him in the quest for the Golden Fleece. Though there were no further kings in Aegina, the kings of Epirus claimed descent from Peleus in the historic period.[205]

- Life myth

- Peleus and his brother Telamon killed their half-brother Phocus, perhaps in a hunting accident and certainly in an unthinking moment,[206] and fled Aegina to escape punishment. In Phthia, Peleus was purified by Eurytion and married Antigone, Eurytion's daughter, by whom he had a daughter, Polydora. Eurytion received the barest mention among the Argonauts (Peleus and Telamon were Argonauts themselves) "yet not together, nor from one place, for they dwelt far apart and distant from Aigina;"[207] but Peleus accidentally killed Eurytion during the hunt for the Calydonian Boar and fled from Phthia.

- Peleus was purified of the murder of Eurytion in Iolcus by Acastus. Astydameia, Acastus' wife, fell in love with Peleus but he scorned her. Bitter, she sent a messenger to Antigone to tell her that Peleus was to marry Acastus' daughter. As a result, Antigone hanged herself.

- Astydameia then told Acastus that Peleus had tried to rape her. Acastus took Peleus on a hunting trip and hid his sword then abandoned him right before a group of centaurs attacked. Chiron, the wise centaur, or, according to another source, Hermes, returned Peleus' sword with magical powers and Peleus managed to escape.[208] He pillaged Iolcus and dismembered Astydameia, then marched his army between the rended limbs. Acastus and Astydamia were dead and the kingdom fell to Jason's son, Thessalus.

- Marriage to Thetis

Peleus makes off with his prize bride Thetis, who has vainly assumed animal forms to escape him: Boeotian black-figure dish, ca. 500 BC–475 BC

- After Antigone's death, Peleus married the sea-nymph Thetis. He was able to win her with the aid of Proteus, who told Peleus how to overcome Thetis' ability to change her form.[209] Their wedding feast was attended by many of the Olympian gods. As a wedding present, Poseidon gave Peleus two immortal horses: Balius and Xanthus. During the feast, Eris produced the Apple of Discord, which started the quarrel that led to the Judgement of Paris and eventually to the Trojan War. The marriage of Peleus and Thetis produced seven sons, six of whom died in infancy. The only surviving son was Achilles.

- Peleus' son Achilles

- Thetis attempted to render her son Achilles invulnerable. In a familiar version, she dipped him in the River Styx, holding him by one heel, which remained vulnerable. In an early and less popular version of the story, Thetis anointed the boy in ambrosia and put him on top of a fire to burn away the mortal parts of his body. She was interrupted by Peleus and she abandoned both father and son in a rage, leaving his heel vulnerable. A nearly identical story is told by Plutarch, in his On Isis and Osiris, of the goddess Isis burning away the mortality of Prince Maneros of Byblos, son of Queen Astarte, and being likewise interrupted before completing the process.

- Peleus gave Achilles to the centaur Chiron, to raise on Mt. Pelion, which took its name from Peleus.

- In the Iliad, Achilles uses Peleus' immortal horses and also wields his father's spear.

Achilles and the Nereid Cymothoe: Attic red-figure kantharos from Volci (Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque nationale, Paris) - In Greek mythology, Achilles (Ἀχιλλεύς, Akhilleus, 발음 [akʰillěws]) was a Greek hero of the Trojan War and the central character and greatest warrior of Homer's Iliad. Achilles was said to be a demigod; his mother was the nymph Thetis, and his father, Peleus, was the king of the Myrmidons.

- Achilles’ most notable feat during the Trojan War was the slaying of the Trojan hero Hector outside the gates of Troy. Although the death of Achilles is not presented in the Iliad, other sources concur that he was killed near the end of the Trojan War by Paris, who shot him in the heel with an arrow. Later legends (beginning with a poem by Statius in the 1st century AD) state that Achilles was invulnerable in all of his body except for his heel. Because of his death from a small wound in the heel, the term Achilles' heel has come to mean a person's point of weakness.

- Birth

Thetis Dipping the Infant Achilles into the River Styx (ca. 1625), Peter Paul Rubens - Achilles was the son of the nymph Thetis and Peleus, the king of the Myrmidons. Zeus and Poseidon had been rivals for the hand of Thetis until Prometheus, the fore-thinker, warned Zeus of a prophecy that Thetis would bear a son greater than his father. For this reason, the two gods withdrew their pursuit, and had her wed Peleus.[210]

- As with most mythology, there is a tale which offers an alternative version of these events: in Argonautica (iv.760) Zeus' sister and wife Hera alludes to Thetis' chaste resistance to the advances of Zeus, that Thetis was so loyal to Hera's marriage bond that she coolly rejected him. Thetis, although a daughter of the sea-god Nereus, was also brought up by Hera, further explaining her resistance to the advances of Zeus.

The Education of Achilles (ca. 1772), by James Barry

- According to the Achilleid, written by Statius in the 1st century AD, and to no surviving previous sources, when Achilles was born Thetis tried to make him immortal, by dipping him in the river Styx. However, he was left vulnerable at the part of the body by which she held him, his heel[211] (see Achilles heel, Achilles' tendon). It is not clear if this version of events was known earlier. In another version of this story, Thetis anointed the boy in ambrosia and put him on top of a fire, to burn away the mortal parts of his body. She was interrupted by Peleus and abandoned both father and son in a rage.[212]

- However, none of the sources before Statius makes any reference to this general invulnerability. To the contrary, in the Iliad Homer mentions Achilles being wounded: in Book 21 the Paeonian hero Asteropaeus, son of Pelagon, challenged Achilles by the river Scamander. He cast two spears at once, one grazed Achilles' elbow, "drawing a spurt of blood".

- Also, in the fragmentary poems of the Epic Cycle in which we can find description of the hero's death, Cypria (unknown author), Aithiopis by Arctinus of Miletus, Little Iliad by Lesche of Mytilene, Iliou persis by Arctinus of Miletus, there is no trace of any reference to his general invulnerability or his famous weakness (heel); in the later vase paintings presenting Achilles' death, the arrow (or in many cases, arrows) hit his body.

- Achilles in the Trojan War