사용자:배우는사람/문서:Nimrod

Nimrod (/ˈnɪm.rɒd/,[1] 히브리어: נִמְרוֹדֿ, 현대 히브리어: Nimrod, 티베리아 히브리어: Nimrōḏ ܢܡܪܘܕ نمرود), king of Shinar, was, according to the Book of Genesis and Books of Chronicles, the son of Cush and great-grandson of Noah. He is depicted in the Tanakh as a man of power in the earth, and a mighty hunter. Extra-biblical traditions associating him with the Tower of Babel led to his reputation as a king who was rebellious against God. Several Mesopotamian ruins were given Nimrod's name by 8th-century Arabs[2] (see Nimrud).

Biblical account 편집

The first mention of Nimrod is in the Table of Nations.[2] He is described as the son of Cush, grandson of Ham, and great-grandson of Noah; and as "a mighty one on the earth" and "a mighty hunter before God". This is repeated in the First Book of Chronicles 1:10, and the "Land of Nimrod" used as a synonym for Assyria or Mesopotamia, is mentioned in the Book of Micah 5:6:

- And they shall waste the land of Assyria with the sword, and the land of Nimrod in the entrances thereof: thus shall he deliver us from the Assyrian, when he cometh into our land, and when he treadeth within our borders.

Genesis says that the "beginning of his kingdom" (reshit memelketo) was the towns of "Babel, Uruk, Akkad and Calneh in the land of Shinar" (Mesopotamia) — understood variously to imply that he either founded these cities, ruled over them, or both. Owing to an ambiguity in the original Hebrew text, it is unclear whether it is he or Asshur who additionally built Nineveh, Resen, Rehoboth-Ir and Calah (both interpretations are reflected in various English versions). (Genesis 10:8–12) (Genesis 10:8-12; 1 Chronicles 1:10, Micah 5:6). Sir Walter Raleigh devoted several pages in his History of the World (c. 1616) to reciting past scholarship regarding the question of whether it had been Nimrod or Ashur who built the cities in Assyria.[3]

Traditions and legends 편집

In Hebrew and Christian tradition, Nimrod is traditionally considered the leader of those who built the Tower of Babel in the land of Shinar,[4] though the Bible never actually states this. Nimrod's kingdom included the cities of Babel, Erech, Accad, and Calneh, all in Shinar. (Ge 10:10) Therefore it was likely under his direction that the building of Babel and its tower began; in addition to Flavius Josephus, this is also the view found in the Talmud (Chullin 89a, Pesahim 94b, Erubin 53a, Avodah Zarah 53b), and later midrash such as Genesis Rabba. Several of these early Judaic sources also assert that the king Amraphel, who wars with Abraham later in Genesis, is none other than Nimrod himself.

Judaic interpreters as early as Philo and Yochanan ben Zakai (1st century AD) interpreted "a mighty hunter before the Lord" (Heb. : לפני יהוה, lit. "in the face of the Lord") as signifying "in opposition to the Lord"; a similar interpretation is found in Pseudo-Philo, as well as later in Symmachus. Some rabbinic commentators have also connected the name Nimrod with a Hebrew word meaning 'rebel'. In Pseudo-Philo (dated ca. AD 70), Nimrod is made leader of the Hamites; while Joktan as leader of the Semites, and Fenech as leader of the Japhethites, are also associated with the building of the Tower.[5] Versions of this story are again picked up in later works such as Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius (7th century AD).

The Book of Jubilees mentions the name of "Nebrod" (the Greek form of Nimrod) only as being the father of Azurad, the wife of Eber and mother of Peleg (8:7). This account would thus make him an ancestor of Abraham, and hence of all Hebrews.

Josephus wrote:

"Now it was Nimrod who excited them to such an affront and contempt of God. He was the grandson of Ham, the son of Noah, a bold man, and of great strength of hand. He persuaded them not to ascribe it to God, as if it were through his means they were happy, but to believe that it was their own courage which procured that happiness. He also gradually changed the government into tyranny, seeing no other way of turning men from the fear of God, but to bring them into a constant dependence on his power. He also said he would be revenged on God, if he should have a mind to drown the world again; for that he would build a tower too high for the waters to reach. And that he would avenge himself on God for destroying their forefathers.

Now the multitude were very ready to follow the determination of Nimrod, and to esteem it a piece of cowardice to submit to God; and they built a tower, neither sparing any pains, nor being in any degree negligent about the work: and, by reason of the multitude of hands employed in it, it grew very high, sooner than any one could expect; but the thickness of it was so great, and it was so strongly built, that thereby its great height seemed, upon the view, to be less than it really was. It was built of burnt brick, cemented together with mortar, made of bitumen, that it might not be liable to admit water. When God saw that they acted so madly, he did not resolve to destroy them utterly, since they were not grown wiser by the destruction of the former sinners; but he caused a tumult among them, by producing in them diverse languages, and causing that, through the multitude of those languages, they should not be able to understand one another. The place wherein they built the tower is now called Babylon, because of the confusion of that language which they readily understood before; for the Hebrews mean by the word Babel, confusion…"

An early Arabic work known as Kitab al-Magall or the Book of Rolls (part of Clementine literature) states that Nimrod built the towns of Hadâniûn, Ellasar, Seleucia, Ctesiphon, Rûhîn, Atrapatene, Telalôn, and others, that he began his reign as king over earth when Reu was 163, and that he reigned for 69 years, building Nisibis, Raha (Edessa) and Harran when Peleg was 50. It further adds that Nimrod "saw in the sky a piece of black cloth and a crown." He called upon Sasan the weaver and commanded him to make him a crown like it, which he set jewels on and wore. He was allegedly the first king to wear a crown. "For this reason people who knew nothing about it, said that a crown came down to him from heaven." Later, the book describes how Nimrod established fire worship and idolatry, then received instruction in divination for three years from Bouniter, the fourth son of Noah.[6]

In the Recognitions (R 4.29), one version of the Clementines, Nimrod is equated with the legendary Assyrian king Ninus, who first appears in the Greek historian Ctesias as the founder of Nineveh. However, in another version, the Homilies (H 9.4-6), Nimrod is made to be the same as Zoroaster.

The Syriac Cave of Treasures (ca. 350) contains an account of Nimrod very similar to that in the Kitab al-Magall, except that Nisibis, Edessa and Harran are said to be built by Nimrod when Reu was 50, and that he began his reign as the first king when Reu was 130. In this version, the weaver is called Sisan, and the fourth son of Noah is called Yonton.

Jerome, writing ca. 390, explains in Hebrew Questions on Genesis that after Nimrod reigned in Babel, "he also reigned in Arach [Erech], that is, in Edissa; and in Achad [Accad], which is now called Nisibis; and in Chalanne [Calneh], which was later called Seleucia after King Seleucus when its name had been changed, and which is now in actual fact called Ctesiphon." However, this traditional identification of the cities built by Nimrod in Genesis is no longer accepted by modern scholars, who consider them to be located in Sumer, not Syria.

The Ge'ez Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan (ca. 5th century) also contains a version similar to that in the Cave of Treasures, but the crown maker is called Santal, and the name of Noah's fourth son who instructs Nimrod is Barvin.

However, Ephrem the Syrian (306-373) relates a contradictory view, that Nimrod was righteous and opposed the builders of the Tower. Similarly, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (date uncertain) mentions a Jewish tradition that Nimrod left Shinar and fled to Assyria, because he refused to take part in building the Tower — for which God rewarded him with the four cities in Assyria, to substitute for the ones in Babel.

Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer (c. 833) relates the Jewish traditions that Nimrod inherited the garments of Adam and Eve from his father Cush, and that these made him invincible. Nimrod's party then defeated the Japhethites to assume universal rulership. Later, Esau (grandson of Abraham), ambushed, beheaded, and robbed Nimrod. These stories later reappear in other sources including the 16th century Sefer haYashar, which adds that Nimrod had a son named Mardon who was even more wicked.[7]

In the History of the Prophets and Kings by the 9th century Muslim historian al-Tabari, Nimrod has the tower built in Babil, Allah destroys it, and the language of mankind, formerly Syriac, is then confused into 72 languages. Another Muslim historian of the 13th century, Abu al-Fida, relates the same story, adding that the patriarch Eber (an ancestor of Abraham) was allowed to keep the original tongue, Hebrew in this case, because he would not partake in the building. The 10th-century Muslim historian Masudi recounts a legend making the Nimrod who built the tower to be the son of Mash, the son of Aram, son of Shem, adding that he reigned 500 years over the Nabateans. Later, Masudi lists Nimrod as the first king of Babylon, and states that he dug great canals and reigned 60 years. Still elsewhere, he mentions another king Nimrod, son of Canaan, as the one who introduced astrology and attempted to kill Abraham.

In Armenian legend, the ancestor of the Armenian people, Hayk, defeated Nimrod (sometimes equated with Bel) in a battle near Lake Van.

In the Hungarian legend of the Enchanted Stag (more commonly known as the White Stag [Fehér Szarvas] or Silver Stag), King Nimród (aka Ménrót and often described as "Nimród the Giant" or "the giant Nimród", descendant of one of Noah's "most wicked" sons, Kam - references abound in traditions, legends, several religions and historical sources to persons and nations bearing the name of Kam or Kám, and overwhelmingly, the connotations are negative), is the first person referred to as forefather of the Hungarians. He, along with his entire nation, is also the giant responsible for the building of the Tower of Babel - construction of which was supposedly started by him 201 years after the event of the Great Flood (see biblical story of Noah's Ark &c.). After the catastrophic failure (through God's will) of that most ambitious endeavour and in the midst of the ensuing linguistic cacophony, Nimród the giant moved to the land of Evilát, where his wife, Enéh gave birth to twin brothers Hunor and Magyar (aka Magor). Father and sons were, all three of them, prodigious hunters, but Nimród especially is the archetypal, consummate, legendary hunter and archer. Both the Huns' and Magyars' historically attested skill with the recurve bow and arrow are attributed to Nimród. (Simon Kézai, personal "court priest" of King László Kún, in his Gesta Hungarorum, 1282-85. This tradition can also be found in over twenty other medieval Hungarian chronicles, as well as a German one, according to Dr Antal Endrey in an article published in 1979).

The twin sons of King Nimród, Hunor and Magor, each with 100 warriors, followed the White Stag through the Meotis Marsh, where they lost sight of the magnificent animal. Hunor and Magor found the two daughters of King Dul of the Alans, together with their handmaidens, whom they kidnapped. Hungarian legends held Hunor and Magyar (aka Magor) to be ancestors of the Huns and the Magyars (Hungarians), respectively. According to the Miholjanec legend, Stephen V of Hungary had in front of his tent a golden plate with the inscription: "Attila, the son of Bendeuci, grandson of the great Nimrod, born at Engedi: By the Grace of God King of the Huns, Medes, Goths, Dacians, the horrors of the world and the scourge of God."

The evil Nimrod vs. the righteous Abraham 편집

The Bible does not mention any meeting between Nimrod and Abraham, although a confrontation between the two is said to have taken place, according to several Jewish and Islamic traditions. Some stories bring them both together in a cataclysmic collision, seen as a symbol of the confrontation between Good and Evil, and/or as a symbol of monotheism against polytheism. On the other hand, some Jewish traditions say only that the two men met and had a discussion.[12]

According to K. van der Toorn; P. W. van der Horst, this tradition is first attested in the writings of Pseudo-Philo.[8] The story is also found in the Talmud, and in rabbinical writings in the Middle Ages.[9]

In some versions (as in Flavius Josephus), Nimrod is a man who sets his will against that of God. In others, he proclaims himself a god and is worshipped as such by his subjects, sometimes with his consort Semiramis worshipped as a goddess at his side. (See also Ninus.)

A portent in the stars tells Nimrod and his astrologers of the impending birth of Abraham, who would put an end to idolatry. Nimrod therefore orders the killing of all newborn babies. However, Abraham's mother escapes into the fields and gives birth secretly. At a young age, Abraham recognizes God and starts worshiping Him. He confronts Nimrod and tells him face-to-face to cease his idolatry, whereupon Nimrod orders him burned at the stake. In some versions, Nimrod has his subjects gather wood for four whole years, so as to burn Abraham in the biggest bonfire the world had ever seen. Yet when the fire is lit, Abraham walks out unscathed.

In some versions, Nimrod then challenges Abraham to battle. When Nimrod appears at the head of enormous armies, Abraham produces an army of gnats which destroys Nimrod's army. Some accounts have a gnat or mosquito enter Nimrod's brain and drive him out of his mind (a divine retribution which Jewish tradition also assigned to the Roman Emperor Titus, destroyer of the Temple in Jerusalem).

In some versions, Nimrod repents and accepts God, offering numerous sacrifices that God rejects (as with Cain). Other versions have Nimrod give to Abraham, as a conciliatory gift, the slave Eliezer, whom some accounts describe as Nimrod's own son. (The Bible also mentions Eliezer as Abraham's majordomo, though not making any connection between him and Nimrod.)

Still other versions have Nimrod persisting in his rebellion against God, or resuming it. Indeed, Abraham's crucial act of leaving Mesopotamia and settling in Canaan is sometimes interpreted as an escape from Nimrod's revenge. Accounts considered canonical place the building of the Tower many generations before Abraham's birth (as in the Bible, also Jubilees); however in others, it is a later rebellion after Nimrod failed in his confrontation with Abraham. In still other versions, Nimrod does not give up after the Tower fails, but goes on to try storming Heaven in person, in a chariot driven by birds.

The story attributes to Abraham elements from the story of Moses' birth (the cruel king killing innocent babies, with the midwives ordered to kill them) and from the careers of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego who emerged unscathed from the fire. Nimrod is thus given attributes of two archetypal cruel and persecuting kings - Nebuchadnezzar and Pharaoh. Some Jewish traditions also identified him with Cyrus whose birth according to Herodotus was accompanied by portents which made his grandfather try to kill him.

A confrontation is also found in the Islamic Qur'an, between a king, not mentioned by name, and the Prophet Ibrahim (Arabic version of "Abraham"). Muslim commentators assign Nimrod as the king based on Jewish sources. In Ibrahim's confrontation with the king, the former argues that Allah (God) is the one who gives life and gives death. The king responds by bringing out two people sentenced to death. He releases one and kills the other as a poor attempt at making a point that he also brings life and death. Ibrahim refutes him by stating that Allah brings the Sun up from the East, and so he asks the king to bring it from the West. The king is then perplexed and angered.

Whether or not conceived as having ultimately repented, Nimrod remained in Jewish and Islamic tradition an emblematic evil person, an archetype of an idolater and a tyrannical king. In rabbinical writings up to the present, he is almost invariably referred to as "Nimrod the Evil" (נמרוד הרשע)"

The story of Abraham's confrontation with Nimrod did not remain within the confines of learned writings and religious treatises, but also conspicuously influenced popular culture. A notable example is "Quando el Rey Nimrod" ("When King Nimrod"), one of the most well-known folksongs in Ladino (the Judeo-Spanish language), apparently written during the reign of King Alfonso X of Castile. Beginning with the words: "When King Nimrod went out to the fields/ Looked at the heavens and at the stars/He saw a holy light in the Jewish quarter/A sign that Abraham, our father, was about to be born", the song gives a poetic account of the persecutions perpetrated by the cruel Nimrod and the miraculous birth and deeds of the savior Abraham.[10]

Text of the Midrash Rabba version 편집

The following version of the Abraham vs. Nimrod confrontation appears in the Midrash Rabba, a major compilation of Jewish Scriptural exegesis. The part relating to Genesis, in which this appears (Chapter 38, 13), is considered to date from the sixth century.

|

נטלו ומסרו לנמרוד. אמר לו: עבוד לאש. אמר לו אברהם: ואעבוד למים, שמכבים את האש? אמר לו נמרוד: עבוד למים! אמר לו: אם כך, אעבוד לענן, שנושא את המים? אמר לו: עבוד לענן! אמר לו: אם כך, אעבוד לרוח, שמפזרת עננים? אמר לו: עבוד לרוח! אמר לו: ונעבוד לבן אדם, שסובל הרוחות? אמר לו: מילים אתה מכביר, אני איני משתחוה אלא לאוּר - הרי אני משליכך בתוכו, ויבא אלוה שאתה משתחוה לו ויצילך הימנו! היה שם הרן עומד. אמר: מה נפשך, אם ינצח אברהם - אומַר 'משל אברהם אני', ואם ינצח נמרוד - אומַר 'משל נמרוד אני'. כיון שירד אברהם לכבשן האש וניצול, אמרו לו: משל מי אתה? אמר להם: משל אברהם אני! נטלוהו והשליכוהו לאור, ונחמרו בני מעיו ויצא ומת על פני תרח אביו. וכך נאמר: וימת הרן על פני תרח אביו. (בראשית רבה ל"ח, יג) |

(...) He [Abraham] was given over to Nimrod. [Nimrod] told him: Worship the Fire! Abraham said to him: Shall I then worship the water, which puts off the fire! Nimrod told him: Worship the water! [Abraham] said to him: If so, shall I worship the cloud, which carries the water? [Nimrod] told him: Worship the cloud! [Abraham] said to him: If so, shall I worship the wind, which scatters the clouds? [Nimrod] said to him: Worship the wind! [Abraham] said to him: And shall we worship the human, who withstands the wind? Said [Nimrod] to him: You pile words upon words, I bow to none but the fire - in it shall I throw you, and let the God to whom you bow come and save you from it! |

Historical interpretations 편집

Historians and mythographers have long tried to find links between Nimrod and attested historical figures. No king named Nimrod is to be found anywhere in the ancient and extensive Mesopotamian records, including the Assyrian King List, nor the king lists of the Sumerians, Akkadian Empire, Babylonia or Chaldea.

Nimrod as Euechoios · Euechoros · Enmerkar 편집

The Christian Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (c. AD 260/265 – 339/340) as early as the early 4th century, noting that the Chaldean historian Berossus in the 3rd century BC had stated that the first king after the flood was Euechoios of Chaldea, identified him with Nimrod. George Syncellus (c. 800) also had access to Berossus, and he too identified Euechoios with the biblical Nimrod.

More recently, Sumerologists have suggested [the same identifiation] additionally connecting both this Euechoios, and the king of Babylon and grandfather of Gilgamos who appears in the oldest copies of Aelian (c. 200 AD) as Euechoros, with the name of the founder of Uruk known from cuneiform sources as Enmerkar.[11]

Berosos /bəˈrɒsəs/ or Berossus (name possibly derived from /bəˈroʊsəs/; Akkadian: Bēl-rē'ušunu, "Bel is their shepherd"; Βήρωσσος)[12] was a Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer, a priest of Bel Marduk[13] and astronomer who wrote in the Koine Greek language, and who was active at the beginning of the 3rd century BC. Versions of two excerpts of his writings survive, at several removes from the original.

Life and work

Using ancient Babylonian records and texts that are lost to us, Berossus published the Babyloniaca (hereafter, History of Babylonia) in three books some time around 290-278 BC, by the patronage[14] of the Macedonian/Seleucid king, Antiochus I Soter (during the third year of Antiochus I, according to Diodorus Siculus[15]). Certain astrological fragments recorded by Pliny the Elder, Censorinus, Flavius Josephus, and Marcus Vitruvius Pollio are also attributed to Berossus, but are of unknown provenance, or indeed are uncertain as to where they might fit into his History. Vitruvius credits him with the invention of the semi-circular sundial hollowed out of a cubical block.[16] A statue of him was erected in Athens, perhaps attesting to his fame and scholarship as historian and astronomer-astrologer.

A separate work, Procreatio, is attributed to him by the Latin commentaries on Aratus, Commentariorium in Aratum Reliquiae, but there is not any proof of this connection. However, a direct citation (name and title) is rare in antiquity, and it may have referred to Book 1 of his History.

He was born during or before Alexander the Great's reign over Babylon (330-323 BC), with the earliest date suggested as 340 BC. According to Vitruvius's work de Architectura, he relocated eventually to the island of Kos off the coast of Asia Minor and established a school of astrology there,[17] by the patronage of the king of Egypt. However, scholars have questioned whether it would have been possible to work under the Seleucids and then relocate to a region experiencing Ptolemaic control late in life. It is not known when he died.

History of Babylonia

Versions at several removes of the remains of Berossos' lost Babyloniaca are given by two later Greek epitomes that were used by the Christian Eusebius of Caesarea for his Chronological Canons, the Greek manuscripts of which have been lost, but which can be largely recovered by the Latin translation and continuation of Jerome and a surviving Armenian translation.[18][19] The reasons why Berossus wrote the History have not survived, though contemporaneous Greek historians generally did give reasons for the publication of their own histories. It is suggested that it was commissioned by Antiochus I, perhaps desiring a history of one of his newly-acquired lands, or by the Great Temple priests, seeking justification for the worship of Marduk in Seleucid lands. Pure history writing per se was not a Babylonian concern, and Josephus testifies to Berossus' reputation as an astrologer.[20] The excerpts quoted relate mythology and history that relates to Old Testament concerns. As historian and archaeologist W.G. Lambert observes: "Of course Berossus may have written other works which are not quoted by Josephus and Eusebius because they lacked any Biblical interest".[20] Lambert finds some statements in the Latin writers so clearly erroneous that it renders doubtful whether the writers had first-hand knowledge of Berossus' text.

Transmission and reception

Berossus' work was not popular during the Hellenistic period. The usual account of Mesopotamian history was Ctesias of Cnidus's Persica, while most of the value of Berossus was considered to be his astrological writings. Most pagan writers probably never read the History directly, and seem to have been dependent on Posidonius of Apamea (135-50 BC), who cited Berossos in his works. While Poseidonius's accounts have not survived, the writings of these tertiary sources do: Vitruvius Pollio (a contemporary of Caesar Augustus), Pliny the Elder (d. 79 AD), and Seneca the Younger (d. 65 AD). Seven later pagan writers probably transmitted Berossus via Poseidonius through an additional intermediary. They were Aetius (1st or 2nd century AD), Cleomedes (second half of 2nd century AD.), Pausanias (c. 150 AD), Athenaeus (c. 200 AD), Censorinus (3rd century AD), and an anonymous Latin commentator on the Greek poem Phaenomena by Aratus of Soloi (ca. 315-240/39 BC).

Jewish and Christian references to Berossus probably had a different source, either Alexander Polyhistor (c. 65 BC.) or Juba II of Mauretania (c. 50 BC-20 AD) Polyhistor's numerous works included a history of Assyria and Babylonia, while Juba wrote On the Assyrians, both using Berossus as their primary sources. Josephus' records of Berossus include some of the only extant narrative material, but he is likely dependent on Alexander Polyhistor,[출처 필요] even if he did give the impression that he had direct access to Berossus. The fragments of the Babylonaica found in three Christian writers' works are probably dependent on Alexander or Juba (or both). They are Tatianus of Syria (2nd century AD), Theophilus Bishop of Antioch (180 AD), and Titus Flavius Clemens (ca. 200 AD).

Like Poseidonius, neither Alexander's or Juba's works have survived. However, their material on Berossus was recorded by Abydenus (2nd or 3rd century AD) and Sextus Julius Africanus (early 3rd century AD). Their work is also lost, possibly considered too long, but Eusebius Bishop of Caesaria (ca. 260-340 AD), in his work the Chronicon preserved some of their accounts. The Greek text of the Chronicon is also now lost to us but there is an ancient Armenian translation[21] (500-800 AD) of it, and portions are quoted in Georgius Syncellus's Ecloga Chronographica (ca. 800-810 AD). Nothing of Berossus survives in Jerome's Latin translation of Eusebius. Eusebius' other mentions of Berossus in Praeparatio Evangelica are derived from Josephus, Tatianus, and another inconsequential source (the last cite contains only, "Berossus the Babylonian recorded Naboukhodonosoros in his history.").

Christian writers after Eusebius are probably reliant on him, but include Pseudo-Justinus (3rd–5th century), Hesychius of Alexandria (5th century), Agathias (536–582), Moses of Chorene (8th century), an unknown geographer of unknown date, and the Suda (Byzantine dictionary from the 10th century). Thus, what little of Berossus remains is very fragmentary and indirect. The most direct source of material on Berossus is Josephus, received from Alexander Polyhistor. Most of the names in his king-lists and most of the potential narrative content have been lost or completely mangled as a result. Only Eusebius and Josephus preserve narrative material, and both had agendas. Eusebius was looking to construct a consistent chronology across different cultures,[21]틀:Primary source-inline while Josephus was attempting to refute the charges that there was a civilization older than that of the Jews.[출처 필요] However, the ten ante-diluvian kings were preserved by Christian apologists interested in the long lifespans of the kings were similar to the long lifespans of the ante-diluvian ancestors in the story of Genesis.

Sources and content

The Armenian translation of Eusebius and Syncellus' transmission (Chronicon and Ecloga Chronographica respectively) both record Berossus' use of "public records" and it is possible that Berossus catalogued his sources. This did not make him reliable, only that he was careful with the sources and his access to priestly and sacred records allowed him to do what other Babylonians could not. What we have of ancient Mesopotamian myth is somewhat comparable with Berossus, though the exact integrity with which he transmitted his sources is unknown because much of the literature of Mesopotamia has not survived. What is clear is that the form of writing he used was dissimilar to actual Babylonian literature, writing as he did in Greek.

Book 1 fragments are preserved in Eusebius and Syncellus above, and describe the Babylonian creation account and establishment of order, including the defeat of Thalatth (Tiamat) by Bel (Marduk). According to him, all knowledge was revealed to humans by the sea monster Oannes after the Creation, and so Verbrugghe and Wickersham (2000:17) have suggested that this is where the astrological fragments discussed above would fit, if at all.

Book 2 describes the history of the Babylonian kings from creation till Nabonassaros (747-734 BC). Eusebius reports that Apollodorus reports that Berossus recounts 432,000 years from the first king, Aloros, to Xisouthros and the Babylonian Flood. From Berossus' genealogy, it is clear he had access to king-lists in compiling this section of History, particularly in the kings before the Flood (legendary though they are), and from the 7th century BC with Senakheirimos (Sennacherib, who ruled both Assyria and Babylon). His account of the Flood (preserved in Syncellus) is extremely similar to versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh that we have presently. However, in Gilgamesh, the main protagonist (주인공) is Utnapishtim, while for Berossus, Xisouthros is likely a Greek transliteration of Ziusudra, the protagonist of the Sumerian version of the Flood.

Perhaps what Berossus omits to mention is also noteworthy. Much information on Sargon (ca. 2300 BC) would have been available during his time (e.g., a birth legend preserved at El-Amarna and in an Assyrian fragment from 8th century BC, and two Neo-Babylonian fragments), but these were not mentioned. Similarly, the great Babylonian king Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BC) merits only passing mention. He did, however, mention that the queen Semiramis (probably Sammuramat, wife of Samshi-Adad V, 824-811 BC) was Assyrian. Perhaps it was in response to Greek writers mythologising (신화화하다) her to the point where she was described as the founder of Babylon, daughter of the Syrian goddess Derketo, and married to Ninus (the legendary founder of Nineveh, according to Greek authors).

Book 3 relates the history of Babylon from Nabonassaros to Antiochus I (presumably). Again, it is likely that he used king-lists, though it is not known which ones he used. The Mesopotamian documents known as King-List A (one copy from the 6th or 5th centuries BCE) and Chronicle 1 (3 copies with one confidently dated to 500 BCE) are usually suggested as the ones he used, due to the synchronicity between those and his History (though there are some differences). A large part of his history around the time of Naboukhodonosoros (Nebuchadrezzar II, 604-562 BC) and Nabonnedos (Nabonidus, 556-539 BC) survives. Here we see his interpretation of history for the first time, moralising about the success and failure of kings based on their moral conduct. This is similar to another Babylonian history, Chronicle of Nabonidus (as well as to the Hebrew Bible), and differs from the rationalistic accounts of other Greek historians like Thucydides.

The achievements of History of Babylonia

Berossus' achievement may be seen in terms of how he combined the Hellenistic methods of historiography and Mesopotamian accounts to form a unique composite. Like Herodotus and Thucydides, he probably autographed (자서하다, 사인을 해주다) his work for the benefit of later writers. Certainly he furnished details of his own life within his histories, which contrasted with the Mesopotamian tradition of anonymous scribes. Elsewhere, he included a geographical description of Babylonia, similar to that found in Herodotus (on Egypt), and used Greek classifications. There is some evidence that he resisted adding information to his research, especially for the earlier periods with which he was not familiar. Only in Book 3 do we see his opinions begin to enter the picture.

Secondly, he constructed a narrative from Creation to his present, again similar to Herodotus or the Hebrew Bible. Within this construction, the sacred myths blended with history. Whether he shared Hellenistic skepticism about the existence of the gods and their tales is unknown, though it is likely he believed them more than the satirist Ovid, for example. The naturalistic attitude found in Syncellus' transmission is probably more representative of the later Greek authors who transmitted the work than of Berossus himself.

During his own time and later, however, the History of Babylonia was not distributed widely. Verbrugghe and Wickersham argue that the lack of relation between the material in History and the Hellenistic world was not relevant, since Diodorus' equally bizarre book on Egyptian mythology was preserved. Instead, the reduced association between Mesopotamia and the Greco-Roman lands during Parthian rule was partially responsible. Secondly, his material did not include as much narrative, especially of periods with which he was not familiar, even when potential sources for stories were available. They suggest:

- "Perhaps Berossos was a prisoner of his own methodology and purpose. He used ancient records that he refused to flesh out (~에 살을 붙이다), and his account of more recent history, to judge by what remains, contained nothing more than a bare narrative. If Berossos believed in the continuity of history with patterns that repeated themselves (i.e., cycles of events as there were cycles of the stars and planets), a bare narrative would suffice. Indeed, this was more than one would suspect a Babylonian would or could do. Those already steeped in (…에 푹 빠진) Babylonian historical lore would recognize the pattern and understand the interpretation of history Berossos was making. If this, indeed, is what Berossos presumed (당연한 것으로 여기다, 추정하다), he made a mistake that would cost him interested Greek readers who were accustomed to a much more varied and lively historical narrative where there could be no doubt who was an evil ruler and who was not." (2000:32)

What is left of Berossus' writings is useless for the reconstruction of Mesopotamian history. Of greater interest to scholars is his historiography (역사 기록학), using as it did both Greek and Mesopotamian methods. The affinities between it and Hesiod, Herodotus, Manethon, and the Hebrew Bible (specifically, the Torah and Deuteronomistic History) as histories of the ancient world give us an idea about how ancient people viewed their world. Each begins with a fantastic creation story, followed by a mythical ancestral period, and then finally accounts of recent kings who seem to be historical, with no demarcations in between. Blenkinsopp notes:

- "In composing his history, Berossus drew on the mythic-historiographical tradition of Mesopotamia, and specifically on such well known texts as the creation myth Enuma Elish, Atrahasis, and the king lists, which provided the point of departure and conceptual framework for a universal history. But the mythic and archaic element was combined with the chronicles of rulers which can lay claim to being in some degree genuinely historical." (1992:41)

This early approach to historiography, though preceded by Hesiod, Herodotus, and the Hebrew Bible, demonstrates its own unique approach. Though one must be careful about how much can be described of the original work, his apparent resistance to adding to his sources is noteworthy, as is the lack of moralising he introduces to those materials he is not familiar with.

"Pseudo-Berossus"

During 1498, an official of Pope Alexander VI named Annius of Viterbo claimed to have discovered lost books of Berosos. These were in fact an elaborate forgery. However, they greatly [22] influenced Renaissance ways of thinking about population and migration, because Annius provided a list of kings from Japhet onwards, filling a historical gap following the Biblical account of the Flood. Annius also introduced characters from classical sources into the biblical framework, publishing his account as Commentaria super opera diversorum auctorum de antiquitatibus (A History of the antiquities over the works of different authors). One consequence was to result in sophisticated theories about Celtic races with Druid priests in Western Europe.[23]

References

- Blenkinsopp, J. 1992. The Pentateuch: An Introduction to the First Five Books of the Bible. New York: Anchor Doubleday.

- Verbrugghe, G.P. & Wickersham, J.M. 2000. Berossos and Manetho Introduced and Translated: Native Traditions in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- K. Müller, Fragmenta historicorum Graecorum (FHG) 2. Paris: Didot, 1841‑1870, frr. 1‑25.

- Berossus, and Stanley Mayer Burstein. 1978. The Babyloniaca of Berossus. Malibu: Undena Publications.

- Krebs, C. B. 2011. A Most Dangerous Book. Tacitus's Germania from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich. New York: W. W. Norton, pp. 98–104.

External links

George Syncellus (Γεώργιος Σύγκελλος; died after 810) was a Byzantine chronicler and ecclesiastic. He had lived many years in Palestine (probably in the Old Lavra of Saint Chariton or Souka, near Tekoa) as a monk, before coming to Constantinople, where he was appointed syncellus (literally, "Cell-mate") to Tarasius, patriarch of Constantinople. He later retired to a monastery to write what was intended to be his great work, a chronicle of world history, Ekloge chronographias (Εκλογή Χρονογραφίας), or Extract of Chronography. According to Anastasius Bibliothecarius, George "struggled valiantly against heresy [i.e. Iconoclasm (성상(聖像)[우상] 파괴(주의))] and received many punishments from the rulers who raged against the rites of the Church", although the accuracy of the claim is suspect.[24]

As one of several syncelloi (by the end of the 8th century, there were at least two, and probably more) George stood high in the ecclesiastical establishment of Constantinople. The position carried no defined duties, but the incumbent would generally serve as the patriarch's private secretary, and might also be used by the Emperor to limit the movements and actions of a troublesome patriarch (as was the case during the reign of Constantine VI, when several of George's colleagues were set as guards over Patriarch Tarasius). The office would be an imperial gift by the time of Basil I, and was probably so earlier; as such, George may well have owed his position to the Empress Irene. Many syncelloi would go on to become Patriarchs of Constantinople, or Bishops of other sees (for example George's colleague, John, another syncellus under Patriarch Tarasius, who became Metropolitan Bishop of Sardis in 803). George, however, did not follow this path, instead retreating from the world to compose his great chronicle. It would appear that the Emperor Nicephorus I incurred George's disfavour at around the same time: in 808, Nicephorus discovered a plot against him, and punished the suspected conspirators, amongst whom were not only secular figures "but also holy bishops and monks and clergy of the Great Church, including the synkellos...men of high repute and worthy of respect"; it is unknown whether the syncellus in question was George himself or a colleague/successor, but the attack on the clergy, including George's friends and colleagues, would not have endeared the Emperor to George, and is suggested as the motivating factor in the "pathological hatred" towards Nicephorus I in the Chronicle of Theophanes[25] The date of his death is uncertain; a reference in his chronicle makes clear that he was still alive in 810, and he is sometimes described as dying in 811, but there is no evidence for this, and textual evidence in the Chronicle of Theophanes suggests that he was still alive in 813.[26]

His chronicle, as its title implies, is more of a chronological table with notes than a history. Following on from the Syriac chroniclers of his homeland, who were writing in his lifetime under Arab rule in much the same fashion, as well as the Alexandrians Annianus and Panodorus (monks who wrote near the beginning of the 5th century), George used the chronological synchronic structures of Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius of Caesarea, arranging his events strictly in order of time, and naming them in the year which they happened. Consequently, the narrative is regarded as secondary to the need to reference the relation of each event to other events, and as such is continually interrupted by long tables of dates, so markedly that Krumbacher described it as being "rather a great historical list [Geschichtstabelle] with added explanations, than a universal history." George reveals himself as a staunch upholder of orthodoxy, and quotes Greek Fathers such as Gregory Nazianzen and John Chrysostom. But in spite of its religious bias and dry and uninteresting character, the fragments of ancient writers and apocryphal books preserved in it make it especially valuable. For instance, considerable portions of the original text of the Chronicle of Eusebius have been restored by the aid of George's work. His chief authorities were Annianus of Alexandria and Panodorus of Alexandria, through whom George acquired much of his knowledge of the history of Manetho; George also relied heavily on Eusebius, Dexippus and Julius Africanus.

George's chronicle was continued after his death by his friend Theophanes; Theophanes' work was heavily shaped by George's influence, and the latter may have had a greater influence on Theophanes' Chronicle than Theophanes himself. Anastasius, the Papal Librarian, composed a Historia tripartita in Latin, from the chronicles of George Syncellus, Theophanes Confessor, and Patriarch Nicephorus. This work, written between 873 and 875, spread George's preferenced dates for historical events through the West. Meanwhile, in the East George's fame was gradually overshadowed by that of Theophanes.

References

- Editio princeps by Jacques Goar (1652) in Bonn Corpus scriptorum hist. Byz., by Karl Wilhelm Dindorf (1829).

- Heinrich Gelzer, Sextus Julius Africanus, ii. I (1885).

- H Gelzer. Sextus Julius Africanus und die byzantinische Chronographie. New York: B. Franklin, 1967, reprint of Leipzig: 1898.

- K Krumbacher, Geschichte der byzantinische Litteratur (2nd ed., Munich, 1897).

- Mango and Scott, The Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor

- William Adler. Time immemorial: archaic history and its sources in Christian chronography from Julius Africanus to George Syncellus. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, c1989.

- Alden A. Mosshammer, ed., Georgii Syncelli Ecloga chronographica. Leipzig: Teubner, 1984.

- William Adler, Paul Tuffin, translators. The chronography of George Synkellos: a Byzantine chronicle of universal history from the creation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Part of a series on |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

|---|

| Mesopotamian religion |

| Other traditions |

Enmerkar, according to the Sumerian king list, was the builder of Uruk in Sumer, and was said to have reigned for "420 years" (some copies read "900 years").

The king list adds that Enmerkar brought the official kingship with him from the city of E-ana after his father Mesh-ki-ang-gasher, son of Utu, had "entered the sea and disappeared."

Enmerkar is also known from a few other Sumerian legends, most notably Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, where a previous confusion of the languages of mankind is mentioned. In this account, it is Enmerkar himself who is called 'the son of Utu' (the Sumerian sun god). Aside from founding Uruk, Enmerkar is said here to have had a temple built at Eridu, and is even credited with the invention of writing on clay tablets, for the purpose of threatening Aratta into submission. Enmerkar furthermore seeks to restore the disrupted linguistic unity of the inhabited regions around Uruk, listed as Shubur, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki (the region around Akkad), and the Martu land.

Three other texts in the same series describe Enmerkar's reign. In Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana, while describing Enmerkar's continued diplomatic rivalries with Aratta, there is an allusion to Hamazi having been vanquished. In Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave, Enmerkar is seen leading a campaign against Aratta. The fourth and last tablet, Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird, describes Enmerkar's year-long siege of Aratta. It also mentions that fifty years into Enmerkar's reign, the Martu people had arisen in all of Sumer and Akkad, necessitating the building of a wall in the desert to protect Uruk.

In these last two tablets, the character of Lugalbanda is introduced as one of Enmerkar's war chiefs. According to the Sumerian king list, it was this Lugalbanda "the shepherd" who eventually succeeded Enmerkar to the throne of Uruk. Lugalbanda is also named as the father of Gilgamesh, a later king of Uruk, in both Sumerian and Akkadian versions of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

David Rohl has claimed parallels between Enmerkar, builder of Uruk, and Nimrod, ruler of biblical Erech (Uruk) and architect of the Tower of Babel in extra-biblical legends. One parallel Rohl noted is the description "Nimrod the Hunter", and the -kar in Enmerkar also meaning "hunter". Rohl has also suggested that Eridu near Ur is the original site of Babel (Babylon), and that the incomplete ziggurat found there - by far the oldest and largest of its kind - is none other than the remnants of the Biblical tower.[28]

In a legend related by Aelian [29] (ca. AD 200), the king of Babylon, Euechoros or Seuechoros (also appearing in many variants as Sevekhoros, earlier Sacchoras, etc.), is said to be the grandfather of Gilgamos, who later becomes king of Babylon (i.e., Gilgamesh of Uruk). Several recent scholars have suggested that this "Seuechoros" or "Euechoros" is moreover to be identified with Enmerkar of Uruk, as well as the Euechous named by Berossus as being the first king of Chaldea and Assyria. This last name Euechous (also appearing as Evechius, and in many other variants) has long been identified with Nimrod.[30]

External links

| 이전 Mesh-ki-ang-gasher |

Lugal of Uruk ca. 2600 BC, or legendary |

이후 Lugalbanda |

| Ante-Diluvian kings | Alulim · Dumuzid the Shepherd · Ziusudra | 3rd Dynasty of Kish | Kubaba |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Dynasty of Kish | Etana · Enmebaragesi | 3rd Dynasty of Uruk | Lugal-zage-si |

| 1st Dynasty of Uruk | Enmerkar · Lugalbanda · Dumuzid, the Fisherman · Gilgamesh | Dynasty of Akkad | Sargon · Tashlultum · Enheduanna · Rimush · Manishtushu · Naram-Sin · Shar-Kali-Sharri · Dudu · Shu-turul |

| 1st Dynasty of Ur | Meskalamdug · Mesannepada · Puabi | ||

| 2nd Dynasty of Uruk | Enshakushanna | 2nd Dynasty of Lagash | Puzer-Mama · Gudea |

| 1st Dynasty of Lagash | Ur-Nanshe · Eannatum · En-anna-tum I · Entemena · Urukagina | 5th Dynasty of Uruk | Utu-hengal |

| Dynasty of Adab | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | 3rd dynasty of Ur | Ur-Nammu · Shulgi · Amar-Sin · Shu-Sin · Ibbi-Sin |

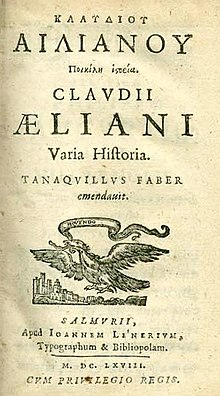

- Aelianus Tacticus, Greek military writer of the 2nd century, resident at Rome, is sometimes confused with Claudius Aelianus.

Claudius Aelianus (ca. 175 – ca. 235) (Κλαύδιος Αἰλιανός),[31] often seen as just Aelian, born at Praeneste, was a Roman author and teacher of rhetoric who flourished under Septimius Severus and probably outlived Elagabalus, who died in 222. He spoke Greek so perfectly that he was called "honey-tongued" (meliglossos); Roman-born, he preferred Greek authors, and wrote in a slightly archaizing Greek himself.

His two chief works are valuable for the numerous quotations from the works of earlier authors, which are otherwise lost, and for the surprising lore, which offers unexpected glimpses into the Greco-Roman world-view.

De Natura Animalium (Περὶ Ζῴων Ἰδιότητος)

On the Nature of Animals, ("On the Characteristics of Animals" is an alternative title; usually cited, though, by its Latin title), is a curious collection, in 17 books, of brief stories of natural history, sometimes selected with an eye to conveying allegorical moral lessons, sometimes because they are just so astonishing:

- "The Beaver is an amphibious creature: by day it lives hidden in rivers, but at night it roams the land, feeding itself with anything that it can find. Now it understands the reason why hunters come after it with such eagerness and impetuosity, and it puts down its head and with its teeth cuts off its testicles and throws them in their path, as a prudent man who, falling into the hands of robbers, sacrifices all that he is carrying, to save his life, and forfeits his possessions by way of ransom. If however it has already saved its life by self-castration and is again pursued, then it stands up and reveals that it offers no ground for their eager pursuit, and releases the hunters from all further exertions, for they esteem its flesh less. Often however Beavers with testicles intact, after escaping as far away as possible, have drawn in the coveted part, and with great skill and ingenuity tricked their pursuers, pretending that they no longer possessed what they were keeping in concealment."

The Loeb Classical Library introduction characterizes the book as

- "an appealing collection of facts and fables about the animal kingdom that invites the reader to ponder contrasts between human and animal behavior."

Aelian's anecdotes on animals rarely depend on direct observation: they are almost entirely taken from written sources, often Pliny the Elder, but also other authors and works now lost, to whom he is thus a valuable witness.[32] He is more attentive to marine life than might be expected, though, and this seems to reflect first-hand personal interest; he often quotes "fishermen". At times he strikes the modern reader as thoroughly credulous, but at others he specifically states that he is merely reporting what is told by others, and even that he does not believe them. Aelian's work is one of the sources of medieval natural history and of the bestiaries of the Middle Ages; in some ways an allegory of the moral world, an Emblem Book.

The text as it has come down to us is badly mangled and garbled and replete with later interpolations.[33] Conrad Gessner (or Gesner), the Swiss scientist and natural historian of the Renaissance, made a Latin translation of Aelian's work, to give it a wider European audience. An English translation by A. F. Scholfield has been published in the Loeb Classical Library, 3 vols. (19[ ]-59).

Varia Historia (Ποικίλη Ἱστορία)

Various History — for the most part preserved only in an abridged form — is Aelian's other well-known work, a miscellany of anecdotes and biographical sketches, lists, pithy maxims, and descriptions of natural wonders and strange local customs, in 14 books, with many surprises for the cultural historian and the mythographer, anecdotes about the famous Greek philosophers, poets, historians, and playwrights and myths instructively retold. The emphasis is on various moralizing tales about heroes and rulers, athletes and wise men; reports about food and drink, different styles in dress or lovers, local habits in giving gifts or entertainments, or in religious beliefs and death customs; and comments on Greek painting. Aelian gives an account of fly fishing, using lures of red wool and feathers, of lacquerwork, serpent worship — Essentially the Various History is a Classical "magazine" in the original senses of that word. He is not perfectly trustworthy in details, and his agenda is always to inculcate culturally "correct" Stoic opinions[출처 필요], perhaps so that his readers will not feel guilty, but Jane Ellen Harrison found survivals of archaic rites mentioned by Aelian very illuminating in her Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (1903, 1922).

The first printing was in 1545. The standard modern text is Mervin R. Dilts's, of 1974.

Two English translations of the Various History, by Fleming (1576) and Stanley (1665) made Aelian's miscellany available to English readers, but after 1665 no English translation appeared, until three English translations appeared almost simultaneously: James G. DeVoto, Claudius Aelianus: Ποιϰίλης Ἱοτορίας ("Varia Historia") Chicago, 1995; Diane Ostrom Johnson, An English Translation of Claudius Aelianus' "Varia Historia", 1997; and N. G. Wilson, Aelian: Historical Miscellany in the Loeb Classical Library.

Other works

Considerable fragments of two other works, On Providence and Divine Manifestations, are preserved in the early medieval encyclopedia, the Suda. Twenty "letters from a farmer" after the manner of Alciphron are also attributed to him. The letters are invented compositions to a fictitious correspondent, which are a device for vignettes of agricultural and rural life, set in Attica, though mellifluous Aelian once boasted that he had never been outside Italy, never been aboard a ship (which is at variance, though, with his own statement, de Natura Animalium XI.40, that he had seen the bull Serapis with his own eyes). Thus conclusions about actual agriculture in the Letters are as likely to evoke Latium as Attica. The fragments have been edited in 1998 by D. Domingo-Foraste, but are not available in English. The Letters are available in the Loeb Classical Library, translated by Allen Rogers Benner and Francis H. Fobes (1949).

See also

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Aelian, On Animals. 3 volumes. Translated by A. F. Scholfield. 1958-9. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 978-0-674-99491-1, ISBN 978-0-674-99493-5, and ISBN 978-0-674-99494-2

- Aelian, Historical Miscellany. Translated by Nigel G. Wilson. 1997. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 978-0-674-99535-2

- Alciphron, Aelian, and Philostratus, The Letters. Translated by A. R. Benner, F. H. Fobes. 1949. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 978-0-674-99421-8

External links

- De natura animalium at LacusCurtius (complete Latin translation)

- Various History at James Eason's site (excerpts in English translation)

- "De natura animalium at Google Books 1866 edition (original Greek)

- Some quotes from Aelian's natural history (English)

- Aelian from the fly-fisherman's point-of-view

- The Evidence for Aelian's Katêgoria tou gunnidos regarding Aelian's presumed invective against Elagabalus

Nimrod as Lugal-Banda, a Lord (Ni) of Marad 편집

J.D.Prince, in 1920 also suggested a possible link between the Lord (Ni) of Marad and Nimrod.

He (J.D.Prince) mentioned how Dr. Kraeling was now inclined to connect Nimrod historically with Lugal-Banda, a mythological king mentioned in Poebel, Historical Texts, 1914, whose seat was at the city Marad.[34] This is supported by Theodore Jacobson in 1989, writing on "Lugalbanda and Ninsuna".[35]

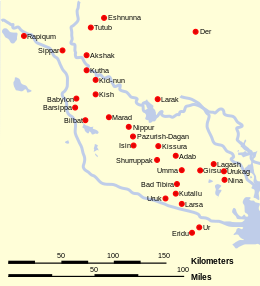

Marad (Sumerian: Marda, modern Tell Wannat es-Sadum or Tell as-Sadoum, Iraq) [37] was an ancient Sumerian city. Marad was situated on the west bank of the then western branch of the Upper Euphrates River west of Nippur in modern day Iraq and roughly 50 km southeast of Kish, on the Arahtu River.

| Marad | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 북위 32° 04′ 00″ 동경 44° 47′ 00″ / 북위 32.06667° 동경 44.78333° |

The city's ziggurat E-igi-kalama [38] was dedicated to Ninurta the god of earth and the plow, built by one of Naram-Sin's sons, as well as the tutelary deity Lugalmarada (also Lugal-Amarda).[39] The city fell into the bounds of the Akkad after the conquest of Sargon of Akkad.

History

Marad was established ca. 2700 BC, during the Sumerian Early Dynastic II period.

Archaeology

The site of Marad covers an area of less than 124 hectares (500 acres).

Marad was excavated by a team from Qādisiyyah University in 1990 led by Naal Hannoon, and in 2005 and 2007 led by Abbas Al-Hussainy.[40] Publication of the last two seasons is in progress.

References

- FS Safar, Old Babylonian contracts from Marad, University of Chicago,1938

See also

Lugalbanda is a character found in Sumerian mythology and literature. His name is composed of two Sumerian words meaning "young king" (lugal: king; banda: young, junior; small).[41][42] Lugalbanda is listed in the postdiluvian period of the Sumerian king list as the second king of Uruk, saying he ruled for 1,200 years, and providing him with the epithet of the Shepherd.[43] Whether a king Lugalbanda ever historically ruled over Uruk, and if so, at what time, is quite uncertain. Attempts to date him in the ED II period are based on an amalgamation of data from the epic traditions of the 2nd Millennium with unclear archaeological observations.[44]

Lugalbanda prominently features as the hero of two Sumerian stories dated to the Ur III period (21st century BCE), called by scholars Lugalbanda I (or Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave) and Lugalbanda II (or Lugalbanda and the Anzu Bird). Both are known only in later versions, although there is an Ur III fragment that is quite different than either 18th century version[45] These tales are part of a series of stories that describe the conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Unug (Uruk), and Ensuhkeshdanna, lord of Aratta, presumably in the Iranian highlands. In these two stories, Lugalbanda is a soldier in the army of Enmerkar, whose name also appears in the Sumerian King List as the first king of Uruk and predecessor of Lugalbanda. The extant fragments make no reference to Lugalbanda's succession as king following Enmerkar.[46]

Lugalbanda appears in Sumerian literary sources as early as the mid-3rd millennium, as attested by a mythological text from Abu Salabikh that describes a romantic relationship between Lugalbanda and Ninsun.[47]

A deified Lugalbanda often appears as the husband of the goddess Ninsun. In the earliest god-lists from Fara, his name appears separate and in a much lower ranking than Ninsun,[48] but in later traditions, until the Seleucid period, his name is often listed in god-lists along with his consort Ninsun.[49] Ample evidence for the worship of Lugalbanda as a deity comes from the Ur III period, as attested in tablets from Nippur, Ur, Umma and Puzrish-Dagan.[50] In Old Babylonian period, Sin-kashid of Uruk is known to have built a temple called É-KI.KAL dedicated to Lugalbanda and Ninsun, and to have assigned his daughter Niši-īnī-šu as the eresh-dingir priestess of Lugalbanda.[51]

In royal hymns of the Ur III period, Ur-Nammu of Ur and his son Shulgi describe Lugalbanda and Ninsun as their holy parents, and in the same context call themselves the brother of Gilgamesh.[52] Sin-Kashid of Uruk also refers to Lugalbanda and Ninsun as his divine parents, and names Lugalbanda as his god.[53]

In the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh and in earlier Sumerian stories about the hero, the king of Uruk, Gilgamesh, calls himself the son of Lugalbanda and Ninsun. In the Gilgamesh and Huwawa tale, the hero consistently uses the assertive phrase: “By the life of my own mother Ninsun and of my father, holy Lugalbanda!”.[54][55] In Akkadian versions of the epic, Gilgamesh also refers to Lugalbanda as his personal god, and in one episode presents the oil filled horns of the defeated Bull of Heaven "for the anointing of his god Lugalbanda".[56]

See also

External links

| 이전 Enmerkar |

Lugal of Uruk ca. 2600 BC or legendary |

이후 Dumuzid, the Fisherman |

| Ante-Diluvian kings | Alulim · Dumuzid the Shepherd · Ziusudra | 3rd Dynasty of Kish | Kubaba |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Dynasty of Kish | Etana · Enmebaragesi | 3rd Dynasty of Uruk | Lugal-zage-si |

| 1st Dynasty of Uruk | Enmerkar · Lugalbanda · Dumuzid, the Fisherman · Gilgamesh | Dynasty of Akkad | Sargon · Tashlultum · Enheduanna · Rimush · Manishtushu · Naram-Sin · Shar-Kali-Sharri · Dudu · Shu-turul |

| 1st Dynasty of Ur | Meskalamdug · Mesannepada · Puabi | ||

| 2nd Dynasty of Uruk | Enshakushanna | 2nd Dynasty of Lagash | Puzer-Mama · Gudea |

| 1st Dynasty of Lagash | Ur-Nanshe · Eannatum · En-anna-tum I · Entemena · Urukagina | 5th Dynasty of Uruk | Utu-hengal |

| Dynasty of Adab | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | 3rd dynasty of Ur | Ur-Nammu · Shulgi · Amar-Sin · Shu-Sin · Ibbi-Sin |

Nimrod as Ninurta 편집

According to Ronald Hendel the name Nimrod is probably a polemical distortion of Ninurta, who had cult centers in Babel and Calah, and was a patron god of the Neo-Assyrian kings.[57]

| Part of a series on |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

|---|

| Mesopotamian religion |

| Other traditions |

Ninurta (Nin Ur: God of War) in Sumerian and the Akkadian mythology of Assyria and Babylonia, was the god of Lagash, identified with Ningirsu with whom he may always have been identified. In older transliteration the name is rendered Ninib and Ninip, and in early commentary he was sometimes portrayed as a solar deity.

In Nippur, Ninurta was worshiped as part of a triad of deities including his father, Enlil and his mother, Ninlil. In variant mythology, his mother is said to be the harvest goddess Ninhursag. The consort of Ninurta was Ugallu in Nippur and Bau when he was called Ningirsu.

Ninurta often appears holding a bow and arrow, a sickle sword, or a mace named Sharur: Sharur is capable of speech in the Sumerian legend "Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta" and can take the form of a winged lion and may represent an archetype for the later Shedu.

In another legend, Ninurta battles a birdlike monster called Imdugud (Akkadian: Anzû); a Babylonian version relates how the monster Anzû steals the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil. The Tablets of Destiny were believed to contain the details of fate and the future.

Ninurta slays each of the monsters later known as the "Slain Heroes" (the Warrior Dragon, the Palm Tree King, Lord Saman-ana, the Bison-beast, the Mermaid, the Seven-headed Snake, the Six-headed Wild Ram), and despoils them of valuable items such as Gypsum, Strong Copper, and the Magilum boat [13]). Eventually, Anzû is killed by Ninurta who delivers the Tablet of Destiny to his father, Enlil.

Cults

The cult of Ninurta can be traced back to the oldest period of Sumerian history. In the inscriptions found at Lagash he appears under his name Ningirsu, "the lord of Girsu", Girsu being the name of a city where he was considered the patron deity.

Ninurta appears in a double capacity in the epithets bestowed on him, and in the hymns and incantations addressed to him. On the one hand he is a farmer and a healing god who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons; on the other he is the god of the South Wind as the son of Enlil, displacing his mother Ninlil who was earlier held to be the goddess of the South Wind. Enlil's brother, Enki, was portrayed as Ninurta's mentor from whom Ninurta was entrusted several powerful Mes, including the Deluge.

He remained popular under the Assyrians: two kings of Assyria bore the name Tukulti-Ninurta. Ashurnasirpal II (883—859 BCE) built him a temple in the capital city of Calah (now Nimrud). In Assyria, Ninurta was worshipped alongside the gods Aššur and Mulissu.

In the late neo-Babylonian and early Persian period, syncretism seems to have fused Ninurta's character with that of Nergal. The two gods were often invoked together, and spoken of as if they were one divinity.

In the astral-theological system Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn, or perhaps as offspring or an aspect of Saturn. In his capacity as a farmer-god, there are similarities between Ninurta and the Greek Titan Kronos, whom the Romans in turn identified with their Titan Saturn.

Parts of this article were originally from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article on Ninib.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Ninib〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Ninib〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

See also

External links

- Texts

- Commentary

"Ninib", 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

Ninib

The ideographic (표의 문자의[로 이루어진], 표의적인) designation of a solar deity of Babylonia. The phonetic designation is uncertain - perhaps Annshit. The cult of Ninib can be traced back to the oldest period of Babylonian history. In the inscriptions found at Shirgulla (or Shirpurla, also known as Lagash), he appears as Nin-girsu, that is, "the lord of Girsu," which appears to have been a quarter of Shirgulla. He is closely associated with Bel, or En-lil of Nippur, as whose son he is commonly designated. The combination points to the amalgamation of the district in which Ninib was worshipped with the one in which Bel was the chief deity. This district may have been Shirgulla and surrounding places, which, as we know, fell at one time under the control of the rulers of Nippur.

Ninib appears in a double capacity in the epithets bestowed on him, and in the hymns and incantations addressed to him. On the one hand he is the healing god who releases from sickness and the ban of the demons in general, and on the other he is the god of war and of the chase, armed with terrible weapons. It is not easy to reconcile these two phases, except on the assumption xix. 23 that he has absorbed in his person various minor solar deities, representing different phases of the sun, just as subsequently Shamash absorbed the attributes of practically all the minor sun-deities.

In the systematized pantheon, Ninib survives the tendency towards centralizing all sun cults in Shamash by being made the symbol of a certain phase of the sun. Whether this phase is that of the morning sun or of the springtime with which beneficent qualities are associated, or that of the noonday sun or of the summer solstice, bringing suffering and destruction in its wake, is still a matter of dispute, with the evidence on the whole in favour of the former proposition. At the same time, the possibility of a confusion between Ninib and Nergal must be admitted, and perhaps we are to see the solution of the problem in the recognition of two diverse schools of theological speculation, the one assigning to Ninib the role of the spring-tide (한사리(음력 보름과 그믐 무렵의 밀물이 가장 높은 때)) solar deity, the other identifying him with the sun of the summer solstice. In the astral-theological system Ninib becomes the planet Saturn. The swine seems to have been the animal sacred to him, or to have been one of the symbols under which he is represented. The consort of Ninib was Gula. (M. JA.)

Nimrod as Marduk 편집

Marduk (Merodach), has been suggested as a possible archetype for Nimrod, especially at the beginning of the 20th century. [출처 필요]

Marduk (Sumerian spelling in Akkadian: AMAR.UTU 𒀫𒌓 "solar calf"; perhaps from MERI.DUG; Biblical Hebrew מְרֹדַךְ Merodach; Greek Μαρδοχαῖος,[59] Mardochaios) was the Babylonian name of a late-generation god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon, who, when Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of Hammurabi (18th century BCE), started to slowly rise to the position of the head of the Babylonian pantheon, a position he fully acquired by the second half of the second millennium BCE.

According to The Encyclopedia of Religion, the name Marduk was probably pronounced Marutuk. The etymology of the name Marduk is conjectured as derived from amar-Utu ("bull calf of the sun god Utu"). The origin of Marduk's name may reflect an earlier genealogy, or have had cultural ties to the ancient city of Sippar (whose god was Utu, the sun god), dating back to the third millennium BCE.[60]

In the perfected system of astrology, the planet Jupiter was associated with Marduk by the Hammurabi period.[61]

Mythology

Babylonian

Marduk's original character is obscure but he was later associated with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic.[62] He was also regarded as the son of Ea[63] (Sumerian Enki) and Damkina[64] and the heir of Anu, but whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to people of the time imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who in an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon.[65] There are particularly two gods—Ea and Enlil—whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk.

In the case of Ea, the transfer proceeded pacifically and without effacing the older god. Marduk took over the identity of Asarluhi, the son of Ea and god of magic, so that Marduk was integrated in the pantheon of Eridu where both Ea and Asarluhi originally came from. Father Ea voluntarily recognized the superiority of the son and hands over to him the control of humanity. This association of Marduk and Ea, while indicating primarily the passing of the supremacy once enjoyed by Eridu to Babylon as a religious and political centre, may also reflect an early dependence of Babylon upon Eridu, not necessarily of a political character but, in view of the spread of culture in the Euphrates valley from the south to the north, the recognition of Eridu as the older centre on the part of the younger one.

| Part of a series on |

| Mesopotamian mythology |

|---|

| Mesopotamian religion |

| Other traditions |

Late Bronze Age

While the relationship between Ea and Marduk is marked by harmony and an amicable abdication on the part of the father in favour of his son, Marduk's absorption of the power and prerogatives of Enlil of Nippur was at the expense of the latter's prestige. Babylon became independent in the early 19th century BC, and was initially a small city state, overshadowed by older and more powerful Mesopotamian states such as Isin, Larsa and Assyria. However, after Hammurabi forged an empire in the 18th century BC, turning Babylon into the dominant state in the south, the cult of Marduk eclipsed that of Enlil; although Nippur and the cult of Enlil enjoyed a period of renaissance during the over four centuries of Kassite control in Babylonia (c. 1595 BCE–1157 BCE), the definite and permanent triumph of Marduk over Enlil became felt within Babylonia.

The only serious rival to Marduk after ca. 1750 BCE was the god Aššur (Ashur) (who had been the supreme deity in the northern Mesopotamian state of Assyria since the 25th century BC) which was the dominant power in the region between the 14th to the late 7th century BC. In the south, Marduk reigned supreme. He is normally referred to as Bel "Lord", also bel rabim "great lord", bêl bêlim "lord of lords", ab-kal ilâni bêl terêti "leader of the gods", aklu bêl terieti "the wise, lord of oracles", muballit mîte "reviver of the dead", etc.

When Babylon became the principal city of southern Mesopotamia during the reign of Hammurabi in the 18th century BC, the patron deity of Babylon was elevated to the level of supreme god. In order to explain how Marduk seized power, Enûma Elish was written, which tells the story of Marduk's birth, heroic deeds and becoming the ruler of the gods. This can be viewed as a form of Mesopotamian apologetics. Also included in this document are the fifty names of Marduk.

In Enûma Elish, a civil war between the gods was growing to a climactic battle. The Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call and was promised the position of head god.

To prepare for battle, he makes a bow, fletches arrows, grabs a mace, throws lightning before him, fills his body with flame, makes a net to encircle Tiamat within it, gathers the four winds so that no part of her could escape, creates seven nasty new winds such as the whirlwind and tornado, and raises up his mightiest weapon, the rain-flood. Then he sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths. In his lips he holds a spell and in one hand he grasps a herb to counter poison.

First, he challenges the leader of the Anunnaki gods, the dragon of the primordial sea Tiamat, to single combat and defeats her by trapping her with his net, blowing her up with his winds, and piercing her belly with an arrow.

Then, he proceeds to defeat Kingu, who Tiamat put in charge of the army and wore the Tablets of Destiny on his breast, and "wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his" and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

Marduk was depicted as a human, often with his symbol the snake-dragon which he had taken over from the god Tishpak. Another symbol that stood for Marduk was the spade.

Babylonian texts talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, "the holy city, the dwelling of their [the other gods] delight".

Nabu, god of wisdom, is a son of Marduk.

The fifty names of Marduk

Leonard W. King in The Seven Tablets of Creation (1902) included fragments of god lists which he considered essential for the reconstruction of the meaning of Marduk's name. Franz Bohl in his 1936 study of the fifty names also referred to King's list. Richard Litke (1958) noticed a similarity between Marduk's names in the An:Anum list and those of the Enuma elish, albeit in a different arrangement. The connection between the An:Anum list and the list in Enuma Elish were established by Walther Sommerfeld (1982), who used the correspondence to argue for a Kassite period composition date of the Enuma elish, although the direct derivation of the Enuma elish list from the An:Anum one was disputed in a review by Wilfred Lambert (1984).[66]

The Marduk Prophecy

The Marduk Prophecy is a text describing the travels of the Marduk idol from Babylon, in which he pays a visit to the land of Ḫatti, corresponding to the statue’s seizure during the sack of the city by Mursilis I in 1531 BC, Assyria, when Tukulti-Ninurta I overthrew Kashtiliash IV in 1225 BC and took the idol to Assur, and Elam, when Kudur-nahhunte ransacked the city and pilfered the statue around 1160 BC. He addresses an assembly of the gods.

The first two sojourns are described in glowing terms as good for both Babylon and the other places Marduk has graciously agreed to visit. The episode in Elam however is a disaster, where the gods have followed Marduk and abandoned Babylon to famine and pestilence. Marduk prophecies that he will return once more to Babylon to a messianic new king, who will bring salvation to the city and who will wreak a terrible revenge on the Elamites. This king is understood to be Nabu-kudurri-uṣur I, 1125-1103 BC.[67] Thereafter the text lists various sacrifices.

A copy[68] was found in the House of the Exorcist at Assur, whose contents date from 713-612 BC and is closely related thematically to another vaticinium ex eventu text called the Shulgi prophecy, which probably followed it in a sequence of tablets.

See also

- Ashur (god)

- Babylonian religion

- Berossus

- Sacred Bull

- Chaldean mythology

- Etemenanki

- Nebuchadnezzar II

- Utu

- Zakmuk

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Marduk〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, 편집. (1911). 〈Marduk〉. 《Encyclopædia Britannica》 11판. Cambridge University Press.

External Links

"Marduk", 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

MARDUK (Bibl. Merodach 2), the name of the patron deity of the city of Babylon, who, when Babylon permanently became the political centre of the united states of the Euphrates valley under Khammurabi ( c. 2250 B.C.), rose to the position of the head of the Babylonian pantheon. His original character was that of a solar deity, and he personifies more specifically the sun of the spring-time who conquers the storms of the winter season. He was thus fitted to become the god who triumphs over chaos that reigned in the beginning of time. This earlier Marduk, however, was effaced by the reflex of the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who at an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon. There are more particularly two gods - Ea and Bel - whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk. In the case of Ea the transfer proceeds pacifically and without involving the effacement of the older god. Marduk is viewed as the son of Ea. The father voluntarily recognizes the superiority of the son and hands over to him the control of humanity. This association of Marduk and Ea, while indicating primarily the passing of the supremacy once enjoyed by Eridu to Babylon as a religious and political centre, may also reflect an early dependence of Babylon upon Eridu, not necessarily of a political character but, in view of the spread of culture in the Euphrates valley from the south to the north, the recognition of Eridu as the older centre on the part of the younger one. At all events, traces of a cult of Marduk at Eridu are to be noted in the religious literature, and the most reasonable explanation for the existence of a god Marduk in Eridu is to assume that Babylon in this way paid its homage to the old settlement at the head of the Persian Gulf.